|

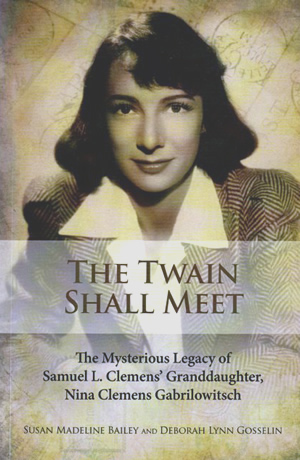

In the summer of 2014, Susan Madeline Bailey caught the attention of Mark Twain scholars and several thousand others with her book The Twain Shall Meet, co-authored by Deborah Gosselin. In it Susan asserted her belief that she was Mark Twain's great-granddaughter. Up to that point, no one had seriously challenged the longstanding view that Samuel Clemens's bloodline came to an end in 1966, when his only grandchild, Nina Gabrilowitsch, died without issue. The book stirred up a flurry of activity on the Mark Twain Forum, a listserv for scholars and fans, and I read the posts with mild interest.

Then, by chance, I met Susan half a year later, in February 2015, the day after a performance of Hal Holbrook's Mark Twain Tonight! in Hartford. I had stopped by the office of Cindy Lovell, Executive Director of the Mark Twain House and Museum, for a brief chat before heading back home to Vermont. Sitting in the office was Susan, a fair, smiling, soft-spoken but also self-possessed 78-year-old. She had flown up from her home in South Carolina to see Holbrook's performance as well. The occasion was the actor's 90th birthday, and Cindy had engineered a post-show celebration onstage, complete with Hartford mayor, Connecticut governor, and "Happy Birthday" sung by an adoring audience. Cindy and Susan joined Holbrook and a few others at a restaurant for his customary late wind-down dinner. The actor sat with Susan, learned of her conviction that she was Nina's daughter, and shared his memories of Nina, whom he had met in the early development of his act. At one point, in an explanatory aside to a puzzled tablemate, he identified Susan as "the illegitimate great-granddaughter of Mark Twain." Susan protested, "I'm legitimate!" Laughing, Holbrook said, "You weren't supposed to hear that."

As Cindy and Susan told me this story, I too laughed, but I also wondered, Is she legitimate? Susan sent me home with a copy of The Twain Shall Meet, which chronicles her seven-year effort to identify her biological parents. I quickly discovered that the book was an unusual mix of childhood memories, speculative reconstruction, and promising DNA evidence. Though skeptical, I found Susan's tale to be fascinating, entirely plausible, and begging for further investigation.

Susan Madeline Bailey, daughter (for all she knew) of Elwood and Drucilla Bailey of Tampa, Florida, was a second grader in Henderson Elementary School in the fall of 1944 when she was summoned to the principal's office. An aunt had arrived to pick her up early. Susan had never met this particular aunt, but the woman -- dressed more elegantly than Susan was accustomed to, wearing gloves on a hot day -- was kind and attentive, and she showed familiarity with Susan's family, which put her at ease. The aunt took the young girl out for a vanilla ice cream soda, then to a movie in a theater across the street. The film was "a musical and had something to do with a fair," Susan recalls in her book. Not long into the show, the lights came up. Police suddenly appeared at their row, ordered them to stand, handcuffed the woman, and put them both into a police car. "I'm sorry," the woman said tearfully to Susan, who was sobbing, afraid she herself had done something wrong. They were driven to Susan's house, where her father scooped her out of the car and, shaking with anger, said, "You don't ever have to worry about that lady. Forget about her! She's an alcoholic."

"That lady," Susan came to believe, was her mother, Nina Gabrilowitsch, visiting her daughter for the first and only time in her life.

The next day, a Tampa aunt (a real one) whisked Susan by train to Chicago, where she would be raised to adulthood by a married cousin named Eileen, older than Susan by 14 years. Susan believes a major reason for the move was to prevent future surprises from the alcoholic mystery woman, but another reason was her father's failing health. Elwood Bailey was dying of cancer, and arrangements would have to be made for Susan's care. Elwood's wife, Drucilla, treated Susan abusively, and her father wanted her in a safe home. Cousin Eileen had lived in Tampa before she married and moved north, and Susan knew her well and loved her.

Growing up in Chicago, Susan made frequent trips with her new family to Detroit to visit other relatives, and it was in this city that a second series of possible intersections with the Clemens family occurred: visits from an "Aunt Clara."

Born in Elmira, New York, in 1874, Clara Langdon Clemens was the only one of Samuel Clemens's four offspring to survive this repeatedly bereaved man. In 1909, she married Ossip Gabrilowitsch, a world-renowned pianist and eventual intimate of Stokowski, Kreisler, Mahler, Stravinsky, and Rachmaninoff. Samuel Clemens died in April of 1910, and four months later Clara gave birth to Nina. (To the eternal puzzlement of Twain biographers, Clara evidently never told her father of her pregnancy. He was lucid to the end and presumably would have welcomed the news.) The Gabrilowitches moved to Munich when Nina was still an infant. When war broke out in 1914, Ossip was arrested in a general roundup of Russians (he was born in St. Petersburg). Through the intercession of conductor Bruno Walter and others, Clara was able to obtain Ossip's release, and the family swiftly moved to the States. Eventually they took up residence in Detroit, where Ossip became the founding director of the Detroit Symphony Orchestra, which he led -- successfully, gloriously -- through the 1920s until his death in 1936.

Now comes Clara from Los Angeles, where she had moved in 1940, and -- according to The Twain Shall Meet -- meets her granddaughter in Detroit, though she hides her identity from the girl by calling herself an aunt. To young Susan's delight, this elegant stranger doted on her, took her out to dinner, and bought her a fur coat. She promised to return and take her to the symphony on her next visit -- which she did, arousing a storm of attention from photographers. Clara, after all, was not only Mark Twain's daughter but was also the returning widow of the orchestra's longtime former director. A third visit was briefer and less memorable except for its sadness. Susan met Clara in a relative's apartment, went out with the relative to look at some police horses, and returned to find Clara gone. She would never see her again. These visits would have occurred between fall 1944 and the end of 1946.

The evidence for these encounters with Susan -- Nina's and then Clara's -- resides entirely in Susan's memory. The book cites no documentary support of Nina's surprise visit -- no police incident report or record of her arrest in Tampa, no news story of a to-do in a local theater (Tampa was a small town then; the incident might have been newsworthy). Similarly, no substantiation of Clara's three meetings with Susan is offered, either in personal letters (much of Clara's correspondence survives), hotel records, news reports, or symphony newsletters. Where did those photographers' pictures end up? Susan knew what she remembered, and that sufficed for her -- as it would for anyone.

The story entails a third encounter between Susan, Nina, and Clara, and that would be the moment of Susan's birth. The known record: Ossip died on September 14, 1936, but neither Clara nor Nina (then age 26) attended the service in Detroit. They also missed the interment in the Clemens family Elmira plot that followed right after. Their absence is surprising, especially that of Clara, who had always embraced her role as first lady of the symphony. The pair instead went to Mexico for two weeks, then back north to Chicago, where they applied for expedited passports, then to New York. They sailed for Europe on October 24 and remained there for three months, a stay punctuated by repeated attempts to connect with Ossip's sister and brother living in Switzerland, Polya and Artur Gabrilowitsch.

Ossip, Clara, and

Nina in the garden of their Detroit home, 1936.

Photo courtesy of the The Mark Twain House and Museum, Hartford, Connecticut.

What was that trip all about? Nina's diary entries in this period led Susan to this reconstruction: in the spring of 1936, while back in Michigan from New York to visit her dying father, Nina had an affair with Elwood Bailey, visiting from Tampa, and she became pregnant. To avoid a scandal, Clara hustled Nina off to Europe (after an unexplained Mexican detour). Once Susan was born, she was delivered to the custody of Ossip's siblings to be raised in Europe, and she was brought to the States sometime after the war broke out. Clara, having experienced the peril of civilian life in wartime with Ossip's arrest in 1914, would have been especially motivated to bring about her granddaughter's immigration.

Susan's memory plays a supporting role in this interpretation. She recalls some otherwise cryptic remarks by the mystery lady who surprised her at school in Tampa. She told Susan that she knew her middle name -- Madeline. "I named you," she said. And "You're a little French girl." Other memories suggest a European toddlerhood, but some of them were hypnotically induced, and others are recurring dreams that Susan treats as windows to her past. She recalls a nanny named Gladys who spoke French and English and an older couple in the household who spoke a different language. She remembers the Atlantic crossing with Gladys, which would have happened before Susan turned four. After their arrival, she remembers the abrupt departure of nanny Gladys, the only true caregiver she had known.

I found reading these chapters of The Twain Shall Meet an exercise in faith. Why, I asked myself, should I believe the fragmented memories and dreams of a young child -- in some instances an extremely young one -- that are supported only by ambiguous events requiring handsprings of interpretation? And yet the nature of Susan's narrative invited belief. Gaps and inconsistencies seemed the result of the vagaries of memory rather than the obfuscations of a liar or distortions of a delusional. And certain elements seemed beyond invention. In the police car where Nina sat handcuffed, Susan vividly recalls Nina's white patent leather purse lying neglected on the dirty floor. At the Detroit concert, when greeters asked Clara if she planned to sit in her box, she said no, they would sit on the floor; Susan took this literally, imagining a picnic-like scene with no chairs, to Clara's amusement. And in the fancy restaurant where Clara took her to dinner, when Susan dropped her fork and reached down for it, Clara, betraying her privileged upbringing, said, "Let the servant pick it up." Someone else at the table said, "Don't you mean the waiter?" and everyone laughed. As I said to Cindy on a later visit to her office, in a huddle over Susan's credibility, "You can't make this shit up."

As for the paltry paper trail, the central event was scandalous, and scandals limit outright mention, encourage coded language, and cause the destruction of papers. Clara is famous for cultivating a respectable public image of her father, to the annoyance of early editors of Twain's works. "A sordid mess" -- that's the way Cindy, during one of our huddles, forcefully described how Clara would have viewed Nina's pregnancy. "She was so worried about reputation. This is the woman who wouldn't even allow Letters from the Earth to be published! The last thing she wanted was a bastard child."

![]()

I interviewed Susan a few months after our initial meeting, again in Cindy's office -- the cozy, remodeled family lodgings of the groom to the Clemens family above the former stables. There were some gaps in Susan's chronicle that I needed to fill, but I also wanted to see how she presented her story. Would she change anything in a retelling?

I asked about the emergence of her theory. When did she stop seeing herself as Elwood and Drucilla's daughter and begin believing she was Elwood and Nina's daughter? She said that from an early age she had been suspicious of Drucilla, who treated her differently from her younger brother, Bobby -- she got whippings while he got cuddles. In her twenties she learned from a family doctor that Drucilla, because she had type AB blood, could not have given birth to Susan, whose blood type was O. The revelation came to Susan not as a surprise but as a relief. But then who was her biological mother? By this time Susan's father was dead, she wasn't on speaking terms with Drucilla, and Eileen, the cousin who had raised her from age seven on, had nothing to say on the subject -- and never would, carrying whatever she knew to the grave.

While living a full life (marrying, having three children, obtaining a college degree, and becoming a dramatic arts professional), Susan made inconclusive forays into genealogy, guided partly by family rumors she had heard over the years that she could be related to Mark Twain through a distant uncle. Those rumors explained to her satisfaction the pleasant Detroit encounters with "Aunt Clara," and though she had since learned that this woman was Mark Twain's daughter, it had never occurred to her that Clara could be her grandmother, nor did she link family lore to the woman who had taken her out for a vanilla ice cream soda when she was in second grade. "All my life that was just a huge hole that I could not fill in," she said. "It was a vivid memory. Why did that woman take me out of school like that? That was the biggest mystery in my life."

That and other mysteries remained until the summer of 2007, when Susan met the woman who would become her co-author, Deborah Gosselin, an energetic genealogist (is there any other kind?) from Ann Arbor, Michigan. Deb, as everyone calls her, connected with Susan via messaging on Ancestry.com, an essential site for genealogical research. She became a consultant and a tireless researcher on Susan's behalf and ended up writing half of the book. On her own, before Deb came along, Susan said, "I didn't get anywhere."

At the outset, neither Susan nor Deb knew a thing about Nina. Then, not long after the women began to pool their efforts, some bombs dropped from the Internet -- photos of Nina and Ossip that bore an uncanny resemblance to Susan's children and grandchildren. That Susan's descendants would resemble Nina was consistent with the kinship rumor Susan had grown up hearing. But Ossip? He was from another planet, or at least another continent, and certainly another family tree. The photographs raised the possibility of a direct ancestral line from Susan up to Nina and up to Clara and Ossip, which led to Samuel Clemens as Susan's great-grandfather. Once she began to consider Nina as her possible mother, she had an explanation for the mysterious Tampa visitor and her words "I named you." Susan said, "It all fell into place pretty quick. It was like all these pieces were here, and they'd been there forever, but I didn't have the main piece to put it together, and I'd say the main piece was the face of Ossip."

I asked Susan about her coming from Europe to the States, which would have happened sometime before April, 1940 (Susan's name appears in the national census taken in her neighborhood that month). Who arranged the journey? "I think Elwood initiated it," she said. "And I think he initiated it with Clara. I think they absolutely hated each other" -- because Elwood, a married man, had had an affair with Clara's daughter -- "but I think they had to come together to get me." Smiling, Susan said, "All of Nina's boyfriends were married. That was one of the criteria. Most women would say, 'Are you married?' and they were looking for 'No, I'm not married.' She was looking for the ring on their finger." There was something familiar -- something familial -- in her amused censure of Nina's waywardness. I thought of the fuzzy photograph in Susan's book showing Nina with a man in a fedora in what appears to be the back stage of a theater. The caption identifies the man as Elwood Bailey. "How sure are you that that man is Elwood?" I asked her. Her eyes hardened with conviction. "Absolutely."

After our talk, I thought about Susan's manner and affect. Her answers usually came quickly, without the hesitation that fabulation would require. It worried me that many of her theories were no more than guesses about family dynamics and history, unfit for broadcast. There was little distinction in her mind between those notions and claims supported by hard evidence. But, I thought, is there a person alive who doesn't have unverifiable theories about his or her own family?

My job was to weed out the subjective from the objective. I believed the core of her story because of the way she told it. To meet Susan is to believe her.

![]()

"She has inserted herself into Nina's story. There is not a single person who has corroborated it. A baby is born in France in 1937. Prove it! How does this baby get to the U.S.? I want to see the evidence. If Nina had been pregnant, somebody would have a letter, somebody's going to have a document, something that suggests this actually happened."

I shouldn't like Mike Stern but I do. He contradicts with a strange mix of glee and moral umbrage; in our phone conversations I never knew whether to laugh or to come back at him with umbrage of my own. In the course of exploring the Gabrilowitsch family tree, I had happened upon Mike's website, gabrilowitz.com (the name has many spellings), and after a few phone talks we finally met in Boston on a beautiful day in May. Mike is publisher of a major online venture capital database that evolved from a business newspaper he published in the city in the 1990s. "I used to distribute them right out there every month," he said, pointing to busy Boylston Street outside the Starbuck's where we met. He is also an occasional genealogist, seized with the impulse to document the Gabrilowitsch family tree on a locust-like schedule that brought him out in 1981, 1996, and 2009, when he created and then added to his record of the Gabrilowitsch family, tracing its members from Russia, Belarus, and Lithuania across four continents. "I have the dubious distinction of being the central repository of knowledge of the Gabrilowitsch family line," he said, about which, by his own appraisal, he is "obsessive."

Nothing on Mike's genealogy website supports or contradicts Susan's central claim. After establishing that, I stayed in touch with him as an expert who had an interest in the subject via Ossip. His personal genealogical quest began when family rumor led him to believe he was related to the distinguished musician. However, he said, "All of my research showed that it was a tale," and this disavowal makes him a paragon of self-denial when it comes to claims of kinship to a famous figure. It also makes him merciless when he scents flimsiness in such a claim by others. Bragging that he was able to analyze data from Lithuania in the 1840s to disprove a certain theory about Ossip's family's roots, he said, "And this information about Nina is 100 years closer to us!" He complained about the absence of evidence that Nina even knew Elwood and scorned the caption in the book that identifies the man pictured with her as Elwood. "At least give me a photo of Elwood Bailey to compare it with!" But what of Susan's detailed, convincing memories? After all, I protested, she is not a novelist. "She is a novelist," he said. He compared her with Tom Wolfe, his favorite writer, in the ability to enter the head of a character -- in this case Nina's, I assumed, recreating her feelings and motives.

Near the end of our talk, I sketched my upcoming travels for Mike: a return trip to Hartford for the archive there; Provo, Utah, for Nina's diaries; Berkeley for documents at the Mark Twain Papers; and probably Detroit and Tampa. Though two decades my junior, Mike shook his head like a father disapproving of a son's folly -- or, more to the point, like a financial advisor horrified by my attraction to an investment dog.

Before we parted, I pointed out that, fanatic though he was about the Gabrilowitsch clan, he mispronounced the name, at least by Ossip's standards: Mike stressed the second syllable whereas Ossip's family put stress on the "o." A stickler for accuracy, he seemed thrown by the news. A small victory for my side.

![]()

One of Susan and Deb's goals in writing The Twain Shall Meet was to tell the story of Nina, whose profile in Mark Twain biographies usually consists of a few sentences describing her as an alcoholic and probable suicide in a Hollywood apartment in 1966. Biographers have tended to treat her misfortune as a fitting coda to Samuel Clemens's final, relatively unhappy years, as if to say, "And then things really went to hell." These summations, while often lacking in sympathy or detail, do not essentially misrepresent the quality of Nina's life. Even Susan and Deb's fuller chronicle suggests that of Nina's 56 years, the second half was checkered, then steeply declining, then miserable -- a vita presumably captured in the title of her lost autobiographical manuscript, A Life Alone.

"International Monkey"

and "Brown Bear."

Photo courtesy of the The Mark Twain House and Museum, Hartford, Connecticut.

Susan and Deb speculate that Nina's giving up her child at age 26 contributed to her subsequent unhappiness, and Deb's research revealed general support for the idea from descendants of Nina's friends and lovers. The authors also dutifully chronicle all of Nina's known or guessed-at love affairs. I often wondered exactly where Elwood ranked in Nina's history. A one-night stand? I asked Susan and she insisted otherwise, stating they had probably known each other for years. Elwood and two Tampa friends -- his brother-in-law Charlie Lucia and Bob Joughin, the former county sheriff -- took frequent pleasure trips from Tampa to Detroit, Charlie's home before moving to Tampa. The "bad boys," as Susan likes to call them, went north over a number of years. She told me she recalled hearing her aunt, Charlie's wife, in drunken tirades, lash into her husband about the road trips, which left her with the child-rearing and domestic duties. In 1936, the presumed year of Susan's conception, Charlie would have been especially likely to travel to Detroit because his mother there was dying. This was when Ossip's decline also brought Nina back from her residence in New York. That is how Elwood and Nina would have come together.

In the midst of their research on Nina's life, a lucky happenstance gave Susan and Deb an intimate glimpse of their subject. A finding aid for the Brigham Young University library appeared online that listed Nina's handwritten diaries, seventeen of them, intermittently covering the years from 1921 through 1941, a period that included the crucial European trip during which Susan believed she was born. The holdings included a complete typed transcript of all of the diaries, of which Susan and Deb each received a copy, and they pored over its thousand single-spaced pages.

I needed to see the diaries for myself -- not just a typed transcript, which is subject to errors and omissions, but the original handwritten pages. In July I flew to Salt Lake City, rented a car, and drove to nearby Provo. Accustomed to the moderate, often misty summer days of the Northeast, by the time I parked my car I felt half-blinded by the glare of the alien Utah sun, and I quickly sought refuge in the subterranean coolness of the library's special collections.

![]()

I was hoping, of course, that Nina's original diaries would contain language that the typist had considered unfit for transcription -- in other words, that they would reveal all. It was a foolish fantasy. The typescript proved to be quite accurate. Moreover, although I had opened the diaries with the intention of finding firmer ground for Susan and Deb's theory about the trip, by the time I closed the most important one, what ground there was had given way.

The European portion of the 1936 diary combines a rather generic tourist's travelogue by Nina with her personal musings about friends back home and expressions of longing for her Michigan boyfriend, Jim Humberstone, a theatrical director and a curator at Henry Ford's Edison Institute in Dearborn. The diary makes no explicit reference to a pregnancy or a delivery, nor is there any mention of Elwood Bailey. This in itself did not surprise me; Susan and Deb would certainly have quoted such language if it had existed. The diary does, however, contain some mysteries that require interpretation.

This much about the trip is clear: Nina and Clara sailed from New York on October 24, 1936, and returned home three months later, sailing from Villefranche, France, on January 27, 1937. Their itinerary was quite simple: Gibraltar on October 29, Naples two days later, then on to Rome for nearly two months of heavy sightseeing in the city and its environs. Nina's December 21 entry looks ahead to a four-day stay in Florence, to begin on December 28. Documents external to the diary confirm her arrival there (without Clara), and then she went on to Bordighera, near the French border. But the diary itself ends on December 22, leaving a gap in Nina's personal record of their European adventure of over a month. No 1937 diary is known to exist.

If Nina became pregnant in Michigan in the spring, she certainly knew she was pregnant when the duo sailed from New York in October, and Clara, if she didn't know, would soon find out. Although the women's actual itinerary in Europe is consistent with a pregnancy hypothesis, and although the sudden diary silence after December 22 is suggestive, especially on the heels of almost daily entries, something else in the diary confounds the hypothesis: the planning for ambitious future travels during the trip itself. After arriving in Rome, on November 9 Clara and Nina went to a travel agency and set up a five-week trip to Egypt to begin on December 27, which would include a Twain-like river cruise. Would it have been wise to be eight or nine months pregnant on a tour boat on the Nile? The plan changed the next day, but not from sensitivity to Nina's condition: they shortened the Egyptian trip and set up a new two-week excursion to Sicily, where they hoped to meet Ossip's siblings, Polya and Artur. That plan survived until November 23, when they postponed their departure for Egypt for nearly a month, to January 24, only to change it two days later to January 22.

I belabor these dates because they seem utterly insensitive to anything like a due date. Their final projected (and unrealized) departure for Egypt -- January 22 -- was just five days before what turned out to be their actual January 27 departure for home.

Although the diary does not refer directly to Nina's pregnancy, The Twain Shall Meet argues that it makes sidelong references to it. Over breakfast on the morning of their New York embarkation, Nina and Clara tried to guess when they would return home from Europe. Nina wanted it to be soon so that she could be with boyfriend Jim Humberstone again: "I bet we'll be back in this country before the first of the year; she bets it will be after. God, I hope I'm right!" They spoke of their timetable as if it hinged on some uncontrollable factor, which delivery of a baby certainly is. However, equally telling against this interpretation is Nina's language upon arriving in Naples a week later: "Freezing cold. Clara disgusted. Already planning an early return to America. I say Amen to that!" If the purpose of the trip to Europe was to have a secret baby, wouldn't the return have to follow the birth of the baby?

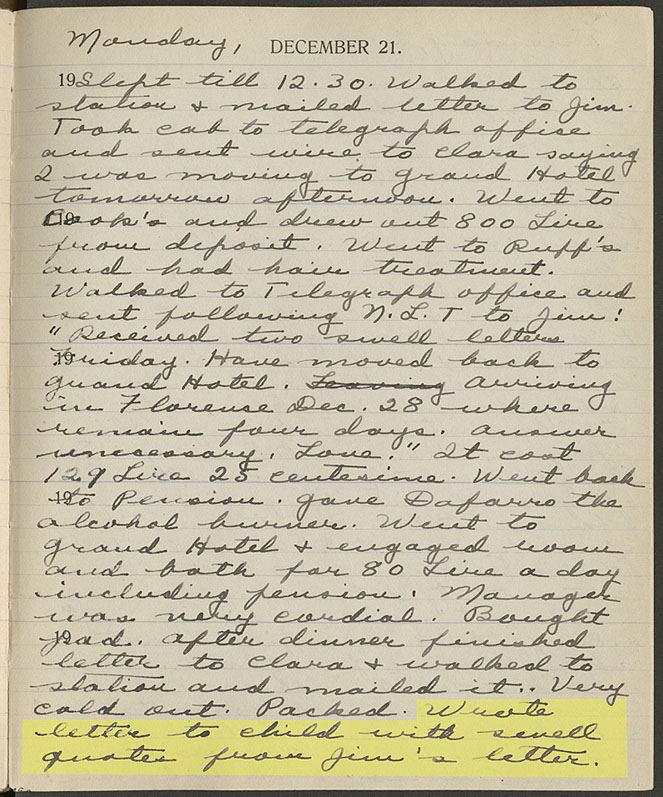

The Twain Shall Meet highlights a diary entry containing the word "child," which falls close to the time when Nina would have been nearing delivery, December 21: "Wrote letter to child with swell quotes from Jim's letter." If Nina was pregnant, she might have thought that Jim Humberstone was the father. It's a striking sentence and a tender image: Nina writes a letter to the child she will soon give birth to with "swell quotes" that give that child an idea of the father's character.

Nina's diary entry, December

21, 1936.

Courtesy of L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Brigham Young University, Provo,

Utah.

The word "mother" also occurs tantalizingly in the documentary record. Marie Therese de Marsano was Nina's Italian teacher in Detroit and a warm friend. On October 6, in Mexico City, Nina (possibly six months pregnant) made the diary entry "Wrote Marsano." On October 17, Marsano wrote a woeful letter to Nina informing her that she had lost her purse and all its contents in the city -- address book, glasses, lipstick, and Nina's letter. "Darling," she wrote, "I am so terribly sorry that had to happen. I kept it in my purse because I did not want it at home . . . Fortunately your letter was signed 'mother' and no where your name." Marsano's relief that Nina did not sign with her name certainly suggests delicate content in the letter, and why, unless Nina was a mother-to-be, would she have signed the lost letter "mother"?

However, other instances of "child" and "mother" in the record nullify the promising import of both of these words. On December 8, in another melancholy letter written to Nina in Rome, Marsano closed with "I love you God bless you and mother your old child." If Nina was about to give birth, in what sense would the newborn be "old"? A different interpretation is that Marsano, in this letter bemoaning her economic plight and dependence on others, is calling herself a "child" -- an "old" one because she was some fifteen years older than Nina. Another passage in the same letter, when read in the light of a later entry in Nina's diary, supports this view. Marsano writes of a "long chat" she had recently had with Humberstone: "He told me that the blond girl is in N.Y. for getting a job -- but he says he really cares for you, let us hope so. I have a little fear that he does not know yet for which one he really cares most." And Marsano then advises Nina to play hard-to-get with Humberstone. Who is "the blond girl"? Probably an actress named Katherine Fields, a rival for Humberstone's affection known to Nina from the previous summer's theater camp in northern Michigan, run by Humberstone. On December 17, by which time Nina could have received Marsano's letter about Humberstone and "the blond girl," Nina made the following complex diary entry: "Wrote long letter to Dot Glenz [a friend from college] telling her about Jim's cable on receiving my postcards and quoted the parts from child's letters about Fields. Told her [i.e. Dot Glenz] Jim must have said something pretty specific to make her [i.e. "child"] feel he didn't know whether he cares most for Fields or me." If Marsano is calling herself an "old child" in her letter about the blond girl, then Nina's reference to the letters about Fields as "child's letters" means that Marsano is the probable "child" of Nina's diary and that Nina is the likely "mother" in relation to her. Over a year later, on Jan. 16, 1938, Marsano ended a letter to Nina with "Good night now god bless you little mother." It is hard to imagine Marsano referring so offhandedly to a real child Nina supposedly gave up a year earlier under what would have been painful circumstances. It is more likely that she is simply referring, perhaps jokingly, to the reversed roles she and Nina had with each other.

Marie Therese de

Marsano and Nina -- wearing wigs.

Photo courtesy of the The Mark Twain House and Museum, Hartford, Connecticut.

Do people keep diaries for posterity or for their private introspection and future reference? Late in life, Nina would sometimes amend personal records with glosses of people named in them, as if conscious of a reader unfamiliar with her full story. But there is nothing like that in her 1936 diary. It is all Nina writing for Nina. There is evidence that Nina sometimes kept more than one diary in a given year, and on this trip she could have made more revealing entries in a second record not governed by a doctrine of secrecy. But a possible diary with supposed content supporting the central claim of The Twain Shall Meet is hardly the same thing as actual evidence for that claim.

In sum, the 1936 diary did not show me that Nina went to Europe in order to give birth in secrecy, and the diary's timetable for future excursions actually argues against that idea. My conclusion was that if Nina gave birth to Susan, she almost certainly did not do so on this trip. And if she did not, there was little basis for the idea that toddler Susan was raised by Ossip's siblings living in Switzerland. Two attractive and plausible elements of Susan's theory were now in serious jeopardy.

I left Provo discouraged but hopeful about what I might find in Berkeley. Nina and Clara waited for me there in over two hundred letters.

![]()

Bob Hirst became General Editor of the Mark Twain Project in 1980. I first met him a few years after that on a research trip to the Mark Twain Papers. The timing of that visit was inauspicious in that I had just seen my father buried in the small Sierra town where I had grown up. Moreover, as I entered the library that day, bells had begun to rain down a melody from the nearby Campanile. When I was young, my father, a proud alumnus, used to take me to the top of the tower when we were in town for Cal football games. Music is always a bad idea when you're grieving, and I pulled into the Mark Twain Papers in shaky condition. The editors, Bob especially, made me feel at home and, in time, much better. You don't forget something like that.

On this visit, Bob swung by the reading room while I was hunched over some documents, welcomed me, and said he would be glad to help in any way he could -- although, he added with a quizzical smile, his interest in the subject was not equal to mine. He then left me to my many boxes. His measured enthusiasm for the subject put him in good company. I knew this because just minutes before, I had stumbled on a sentence that Twain's first biographer, Albert Bigelow Paine, had written to Clara: "I think your father knew very little of the family genealogy, and was not much interested in it."

Almost all of the letters in the Berkeley collection were written not by Nina but to her. But one long letter from Nina to Clara, written in 1960, captures the quality of her life then. It reads like a textbook chapter on depression. Nina reports "black thoughts" and an "utter lack of interest in life." "Each day seems like a nightmare." "I feel like an invalid without really being one." It's doubtful that Nina's mental health improved substantially between then and her death in 1966. A friend writing in 1963 urges her to stay out of "the slough of despond."

Among the letters to Nina is the 1936 lament from Marie Therese de Marsano about the private letter she lost in Detroit -- the one Nina signed with "mother." I thought about what my reaction would have been if I hadn't already read a copy of Marsano's letter and hadn't already subjected it to scrutiny. I would have given it the same weight, and, provisionally at least, the same excited interpretation that Susan and Deb gave it: Nina was a mother-to-be and had written about her condition in the lost letter. "Provisionally"? I flatter myself. I would have been hooked.

And if I ever doubted my inclination to be swayed in Susan's favor, all I had to do was think about my excitement over two meager morsels of support I found, or thought I found, in Berkeley. A July 1944 letter from a close friend of Nina's tells her he just arrived in Fort Jackson, South Carolina. My immediate thought was that if his stay there extended into the fall, it was possible that Nina, living in California, could have put together a trip that included a stop there before or after she surprised Susan at her school in Tampa -- a fall 1944 event. What is wrong with this interpretation? Many things. South Carolina isn't the same as Florida -- it's not even next door. There is no indication how long the soldier would be there, nor is there any mention of a visit. I had created an itinerary that for all its efficiency was no less imaginary.

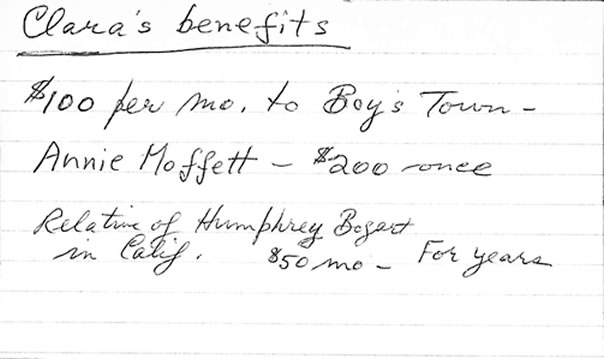

Or consider my reaction to this item that I found as I browsed a large index card file once used by Caroline Harnsberger, an Illinois writer of books about Mark Twain and Clara. I was hoping to find facts too indelicate for inclusion in her respectful biography, Mark Twain's Clara (1982). However, the catalogue consisted almost entirely of Mark Twain quotations -- material for a different book. But Clara was the subject of a few entries, and one in particular excited me, at least provisionally, you might say. It was labeled "Clara's Benefits," and it listed charities Clara had donated to, with amounts given. Among the recipients was this oddity: "Relative of Humphrey Bogart in Calif. $50 mo - For years."

My thinking: In The Twain Shall Meet, Susan writes of mysterious financial support at various points in her young life, and she speculates that Clara, concerned for her granddaughter's welfare and education, was the secret source, hidden by layers of go-betweens. Susan recalls a regular deposit going into her personal account during her college years. The amount was fifty dollars every month. I wondered if "Relative of Humphrey Bogart" was Clara's private moniker for Susan -- a secret from Harnsberger. Or it could have been Harnsberger's private code, or a code they shared, along with a bit of a laugh about using a name like that. Yes, I could see the ladies laughing. After all, why would a relative of Humphrey Bogart's need financial help, and why from Clara? When would she have met this relative, of whom there is no other mention anywhere in her papers? I was excited enough to email recent biographers of the actor to see if they knew of evidence for contact between Clara and an indigent Bogart. If such evidence existed, then Harnsberger's memo was literal, and Susan had nothing to do with it. The biographers were as clueless about the reference as they no doubt were about the reason for my query. But, in the end, I too was clueless. My inability to find a needy Bogart did not mean that one did not exist -- "relative" is a broad term. Here I could take you all over Bogie's family tree, but there would be no point. The point has already been made: I was invested in a positive outcome of my investigation.

Index card from Caroline

Harnsberger's research file.

Courtesy of the Mark Twain Project, The Bancroft Library, University of California,

Berkeley.

Before I left the Mark Twain Papers, I talked with Bob Hirst about hair. Samuel Clemens's secretary and personal assistant, Isabel Lyon, once observed a haircut given to her boss and then carefully collected and labeled some of the results. Bob took me into the vault and showed me the prize -- two flattened curls of wispy, pale yellow cotton candy. We hunkered over it, inexpertly wondering if a follicle was in its midst. I wanted a follicle because strands of hair contain only one kind of DNA, mitochondrial DNA, which is passed forward along the female line. Males can inherit it but cannot pass it on, and so a strand of Sam's hair could not be used to prove or disprove Susan's descent from him. Follicles, though, contain autosomal DNA, which flows down generations gender-neutrally; DNA retrieved from a Sam Clemens follicle could be directly compared with Susan's DNA. Bob said if it came to it, he would be happy to have an expert search the samples for a follicle, though success was highly unlikely since the barber had cut Clemens's hair, not yanked it out by the roots.

Bob sent me off with words of typical good cheer. "Ping me," he said. "I might forget that I've promised something, and I want to help. Ping me."

After I returned home, I contacted Barb Schmidt, one of several Twainians I had been in touch with as I puzzled over Nina's life. Barb runs twainquotes.com, a repository of Mark Twain quotations, newspaper resources, and articles, and she is the pre-eminent problem solver for knotty issues of Twain biography. I sent her my notes on the Nina letters, and they led her to a new theory about Nina and Clara's precipitate trip to Europe. In 1909, Clara, future guardian of reputations, had had a lengthy romance with a married man, Charles Edwin "Will" Wark. Rumors circulated in several newspapers that Wark's wife planned to file an alienation of affection suit naming Clara. The case, if it ever truly existed, was dropped or settled, but it is possible that fear of the very same legal entanglement nearly thirty years later caused Clara to hustle Nina out of the country. Nina's boyfriend, Jim Humberstone, was also a married man, and he was in the midst of a divorce during their trip. On December 28, 1936, he wrote to Nina, "The trial you depict is all wrong -- J.H. is no adulterer nor is N.C. a whatchamaycallit. There can therefore be no accusations nor guilt." "N.C." is doubtless Nina Clemens -- she often used this surname as a stage name. It is hard to know what word "whatchamaycallit" stands for (possibly "corespondent"), but Nina clearly has mentioned some sort of "trial." Humberstone was right in his prediction. There was no such action, and in fact his divorce became final the very next day. But the threat was not a foreign one to the Clemens family.

![]()

Kevin Mac Donnell is the funniest Twainian alive. When he speaks at a conference, you learn to stifle your laughter so as not to miss the line swiftly coming up next. At a professional meeting in Elmira in 2013, I heard him present an original and plausible theory about what prompted Clemens to adopt the pen name "Mark Twain" precisely when he did -- a name from two words long familiar to him from the river. The inspiration, according to Kevin, was its use by another writer in 1861 (two years before Clemens first used it) in a newspaper piece that Clemens was likely to have seen while living in Nevada. When Kevin projected the 1861 newspaper image onto the screen, it was clear that he had given his theory a little boost: "Mark Twain" had been circled, with a Clemens note to self next to it that read, "Use this!" If only literary biography were that easy.

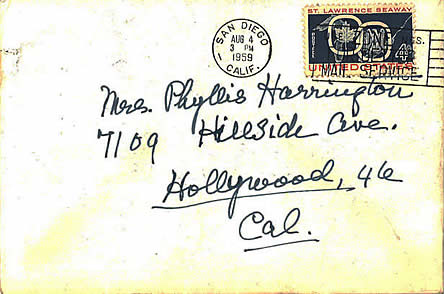

Kevin isn't quick to claim credit for anything -- he prefaced his "Mark Twain" talk with these words about his discovery: "A monkey could have found it! A donkey! My cat!" But credit he must get for guiding my attempts to verify Susan's report of her visits with Clara in Detroit. A collector as well as a scholar, Kevin will often shed light on a Mark Twain Forum discussion with the words "I happen to own . . ." and there is no telling what will follow. What he happened to own in this instance was more than 500 letters written by Clara, several of them dating from the period when she might have gone from Hollywood to Detroit and met Susan. The window for the trip (or trips) was from the fall of 1944 to the end of 1946. Susan moved north some time after school began in 1944, and by the end of 1946 Clara was suffering from a severe case of shingles that probably restricted her travel.

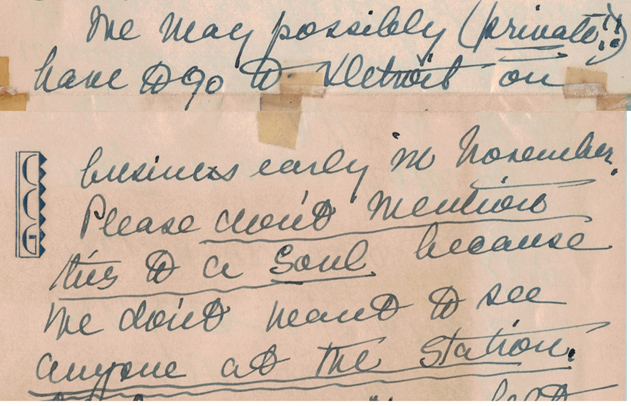

Kevin examined his collection, and he turned up an interesting letter from Clara to Caroline Harnsberger (the biographer whose index cards I rifled in Berkeley), written in October of 1945. Harnsberger lived in Winnetka, Illinois, and Clara wrote that she hoped to see her soon because she would pass through nearby Chicago on her way to Detroit, where she was going "on business." From a page of notes written later by Harnsberger (also in Kevin's possession), we know that Clara and her second husband, Jacques Samossoud, in fact passed through Chicago on November 17, 1945, breakfasted with Harnsberger, and arrived later that day in Detroit, where they stayed until November 28. Thanks to these two documents, we now had independent verification of at least one Clara trip to Detroit in the period when Susan recalled meeting her there. Moreover, in the letter Clara asked Harnsberger -- with underlines -- to keep the trip a secret. "Please don't mention this to a soul because we don't want to see anyone at the station." The warning was exciting. If Clara was going to Detroit to see her illegitimate granddaughter, naturally she wouldn't want people to know about it. The dates were right for the symphony season too. One concert fell in the time frame of Clara's Detroit visit. On Thursday, November 22, Karl Krueger, in his third year as conductor, led the orchestra in Mozart's "Jupiter" Symphony, the Strauss tone poem "Don Juan," American composer William Schumann's Third Symphony, and Kodaly's "Hary Janos Suite."

Excerpt from letter

from Clara to Caroline Harnsberger, Oct. 21, 1945.

Courtesy of Kevin Mac Donnell.

Caroline Harnsberger's

notes on Clara's November 1945 trip to Detroit.

Courtesy of Kevin Mac Donnell.

Detroit's major newspapers are not fully digitized, and this carried a double disadvantage. I would have to go to Michigan and read them on microfilm, and I could not search them with a keyword that might yield instant results. I would go first to Lansing, where the state library had back issues not only of Detroit's major dailies but also of several of the city's foreign language newspapers. Then to Detroit for the symphony archive in the main library.

In Lansing, as I scrolled through papers covering the dates during and immediately following Clara's eleven-day stay, I learned nothing about Clara and Susan. I did learn about the housing shortage facing GIs returning from the war, the happy storming of department stores for nylon stockings available again, and the progress of the Nuremberg trials. I read that the film The Adventures of Mark Twain, with Fredric March as pilot, opened in five Detroit theaters on November 23rd. I learned that Boris Karloff's wife was suing him for divorce, claiming cruelty; I imagined him scaring her, saying "Boo!" all the time. The papers teased me with near misses. The society section described a symphony endowment cocktail party smack in the middle of Clara's stay. I leaned into the screen to read the names of attendees, hoping. The gossip columns "Chatterbox" and "People Are Talking" took note of highbrow visitors from out of town, one after another, an endless parade of nullities. I hated them.

I reread the passage in Susan's book that describes her thrilling experience at the symphony. I could hear the pop of the flash bulbs. I could see the photo -- just one, that was all I needed to confirm the whole story: Clara, seated, poised, smiling, her concern for privacy tossed aside as she warms to the attention. Perhaps her arm would be around Susan sitting beside her. The girl is smartly dressed, her legs too short to reach the floor and swinging freely, and a caption identifies her, perhaps as Clara's "little friend" or even "young Susie Bailey." The picture was so vivid in my mind that I had to remind myself that I hadn't actually seen it.

Since no photo or mention of Clara and Susan appeared in this time frame in any of Detroit's major papers (nor, as far as I could tell, in Gazette van Detroit, Detroiti Ujsag, Dziennik Polski, Athenai, Tribuna Italiana, Ad-Daleel, or any of a dozen other foreign and special-interest newspapers), I revised my search criteria, happy to do so because something had been nagging at me. If Clara had wanted this trip to be secret, would she have taken Susan to a public event and smiled for the cameras? Susan remembered three Detroit encounters with Clara, occurring in this order: (1) cold-weather shopping and fancy dinner; (2) symphony; (3) warm-weather final meeting. Perhaps this known November trip was the first of the series, occurring under a veil of secrecy as Clara tested the waters. Or this known trip could have been the third, coming after the symphony trip with its regrettable exposure, and it was time now for a discreet farewell visit. (Detroit is far from warm in November, but what if Susan's memory of the weather on the third visit was wrong?) I needed to look for Clara at the symphony on both sides of the November dates.

And I did, examining just those papers that appeared within a few days after every concert Clara could conceivably have attended in the 1944-1946 time frame. I also looked at the music programs, which I found in one of several huge orchestra scrapbooks in the Detroit Public Library. Susan had told me about a long-ago incident while riding in the car with her cousin Eileen. They heard Mussorgsky's "A Night on Bald Mountain" on the car radio, and Susan remarked to Eileen that it reminded her of a piece the orchestra had performed the night Clara had taken them to the concert. Eileen agreed with her. I looked for Mussorgsky in the programs, knowing that it was a long shot. I did not find him, though in a sense I did: "A Night on Bald Mountain" raged in my ears as I spooled through newspaper microfilms.

The Detroit Public Library boasts a large archive devoted to Ossip Gabrilowitsch. There I learned that he was a superlative artistic director of the Detroit Symphony Orchestra and an altogether decent fellow. In Bruno Walter's words, "He was of the noble men of music." He had his quirks (he wore high, starched collars and would tear through two of them in a single concert) and his shortcomings (he loved puns, practical jokes, and April Fool's Day). He was generous to the European relatives who regularly hounded him for financial help. He squelched a Columbia Records plan to run a nationwide contest for compositions that would conclude Schubert's "Unfinished Symphony" -- fire seemed to blow out his ears in his written denunciation of it. And he responded to a survey of notable figures by people's intellectual Will Durant, who posed the question, "What is the meaning of life?" Ossip's response was "None." I liked him a lot.

But I hadn't come to Detroit in order to grow fond of Ossip Gabrilowitsch. I wanted to know who "Aunt Clara" was. I was reluctant to believe that it was a mere coincidence that Mark Twain's Clara was definitely in the city on a secretive trip during the period when Susan frequently visited relatives there. In this case I did not find the absence of evidence damning. Photographers take many pictures that never see the light of day. And a bleary-eyed researcher staring at a screen can miss something, or he can err in his selection of which papers to view, which to skip. The evening at the symphony could very well have unfolded just as Susan described it, even if its larger meaning remained unclear.

![]()

Hartford is

less than a four-hour drive from my home, and in the course of the year I made

a number of trips there between longer journeys to other collections. The Hartford

archive, next door to the house where Clemens and his family happily dwelt for

seventeen years, possesses a large collection of Nina's and Clara's letters.

It also has eleven boxes of Nina's photos and a thirty-minute reel of Gabrilowitsch

home movies filmed primarily in the 1920s in Detroit. The Clara collection --

over a thousand letters -- includes substantial correspondence between Clara

and her personal assistant over decades, Phyllis Harrington, who also did her

best to attend to Nina's needs in the years between Clara's death in 1962 and

Nina's four years later.

In the files I saw many of the envelopes that had contained Clara's letters, clearly addressed by her. And licked by her? It was possible, even probable. By this time in her life -- the late fifties and early sixties -- she had no personal assistant other than Harrington, to whom most of the letters were addressed at her home in Los Angeles (Clara now lived in San Diego). Even Clara's faithful chauffeur was dead. And many of the envelopes met a high forensic standard: the writing of Clara's return address in her hand overlapped the sealed flap, suggesting she had inserted the letter, licked and closed the flap, and written the return address over it -- a seamless delivery of her saliva. But even with this sequence, was her DNA retrievable? Kevin Mac Donnell owned many such envelopes in his collection, and in 2014 he had submitted one for testing. Unfortunately, the only DNA found on the flap belonged to one of the lab technicians. Because envelope testing is costly and the results uncertain, and because, for all we knew, Clara could have moistened the flaps with a sponge, I reluctantly shelved this avenue of investigation, knowing as I set each envelope aside that the answer could lie under any one of those flaps.

|

|

Front and back

view of envelope addressed by Clara, 1959.

Courtesy of the The Mark Twain House and Museum, Hartford, Connecticut.

The contents of the letters

were important for two reasons. I wanted to see (1) if there were mentions

of a child of Nina's (or grandchild of Clara's), however obscure the reference,

and (2) if any hint existed of financial help, laundered or otherwise, going

from Clara to Susan. Harrington handled many of Clara's financial transactions

and would have been useful in the transfers. The answer to both questions

was negative -- in the cast of many characters in the letters, neither a nameless

child nor a poor relative of Humphrey Bogart's.

Over several trips, the Hartford archive in fact simply fed my gloom. In The Twain Shall Meet, Susan describes the Gabrilowitsch home movies, and she identifies a couple cavorting at the Gabrilowitsch house as her aunt and Uncle Charlie, one of the "bad boys" who took trips from Tampa to Detroit with Susan's father. "This is key!" I wrote next to that passage when I first read it. If Uncle Charlie appeared in a Gabrilowitsch home movie, it would mean that the Bailey extended family of Tampa interacted with the Gabrilowitsch family of Detroit -- and, by implication, that Elwood could have interacted with Nina. But the photographs available for comparison did not convince me that the couple were Susan's aunt and uncle, and no other evidence of Bailey-Gabrilowitsch contact exists apart from the photo of Nina with the man in the fedora whom Susan identifies as Elwood. And no photograph of Elwood exists that is useful for purposes of comparison.

One picture among the hundreds in the Nina boxes is memorable in two ways -- it is the only photo of an infant in the collection, and it is so blurry as to be hardly worth keeping unless it bore strong emotional value. It shows a baby lying on its back on a couch and being doted on by a seated, dark-haired woman whose face is completely obscured by hair hanging over the side of her face. The book's caption reads, "Slender woman (Nina?) with newborn (Susan?)" It is impossible to say.

Photo from the Nina collection

in Hartford, subjects not identified.

Photo courtesy of the The Mark Twain House and Museum, Hartford, Connecticut.

Another photo in The Twain Shall Meet shows a smiling young blond woman seated on an outdoor patio chair, supporting a blond toddler who is trying to stand or walk. The caption: "Believed to be caretaker Gladys with toddler Susan." Gladys, you will recall, is the nanny whom Susan remembers raising her and conducting her across the ocean to deliver her to Elwood. If that is Gladys and Susan, the time is about a year after Susan's birth, late 1937 or early 1938, and the place is Switzerland or France. But the place is actually southern California. The photo of the toddler and the blond woman is one of a set of eleven photos scattered among the many hundreds of images in Hartford's Nina collection. The sheer volume makes it hard to see the eleven photos as of a piece. (It took me three trips to the place to put them together.) A second photo of the blond woman (sans baby), taken from a different position, shows more of the surroundings, and behind her is some square latticework against a white building. In still another photo, we see Nina herself, wielding a croquet mallet and smiling at the camera against the same background -- square latticework on a white building. In addition, a woman with distinctive features who appears in several of the poolside pictures is identified in other pictures taken elsewhere as Sophie Rosenstein, a drama instructor at Warner Brothers. The story told by the cluster of images is completely at odds with the narrative of The Twain Shall Meet.

Three

photos of a southern California poolside party.

Photos courtesy of the The Mark Twain House and Museum, Hartford, Connecticut.

|

|

Nina Gabrilowitsch

at the same poolside setting.

![]()

The subject was bound to come up sooner or later. Whose body should we dig up? A female would be best, for mitochondrial DNA, and three generations of ladies -- Nina, Clara, and Livy -- reposed unsuspectingly in Elmira.

Or did they? Clara, I quickly learned, was cremated in 1962. As for Nina's body, the evidence pointed in the same direction. Kevin Mac Donnell is always worth quoting: "It just so happens that I have the original funeral home records for Nina's burial. I think Nina was cremated. The record does not specifically say this but in the space for what type of wood was used to make the coffin is the notation 'Wilbert' -- a maker of urns, then and now. It cost $190, so urn-makers have been ripping people off for decades. I'm asking for a ZipLock Bag myself, maybe Tupperware if I'm feeling fancy." (In a separate email, Kevin wrote, "I also have Twain's toe-tag -- actually the tag that was affixed to his coffin to transport it from NY to Elmira, so it has no DNA. Just for the record I did not seek out this creepy stuff; it came to me in an auction lot that included documents and letters.") This meant that the only qualifying female direct-line corpse belonged to Livy, who was buried in 1904. Her memorial reads, "In this grave repose the ashes of Olivia Langdon," but here "ashes" is probably metaphorical, as in "ashes to ashes."

Conversations I had with Twainians suggested that a few were all set to go to the tool shed for their shovels. But Roberta Estes, a genetic genealogist who blogs energetically at dna-explained.com, lays out some of the difficulties in "Digging Up Dad, Exhumation and Forensic Testing Alternatives" (2013). She writes that exhumation requires three things: written consent of all living descendants (not a problem in this case, since no one had undisputed descendant standing -- that was the very goal of the enterprise); a successful petition to a court giving the reasons for the exhumation ("We're curious, Your Honor!"); and at least $20,000. For a recently buried body, Estes reported a 50% chance of usable DNA being retrieved. The blog post does not address the far dimmer prospect of success with ashes. I read elsewhere that DNA can be extracted from teeth, and teeth can survive cremation if the burn temperature is low and the cremains are not completely pulverized. Clara's crematorium was known -- Cypress View Crematory in San Diego -- and it was still in business. What kind of records did they have? It could be an interesting phone call someday.

But not today. Ultimately cool heads prevailed in the informal email thread on the subject that had developed among four or five Twainians. This sentence from one of them pretty much ended it: "My personal opinion is that taking that ultimate step would not reflect positively on Mark Twain scholarship."

![]()

Every other summer, devotees of Mark Twain get together for a conference alternately held in Hannibal or Elmira. As the July 2015 Hannibal conference approached, I was surprised to learn that Susan had been invited to give the opening keynote speech. Would this be a progress report or a coronation? I knew there were many in Twain World who were skeptical of the claims in her book, and I worried about hostile questions.

As it turned out, Susan's presentation was politely received, and she weathered a vigorous Q and A afterward. From the outset of my work on this project, I had seen myself as an outside observer of her quest and of the Twain community's response to it. As such, I sat comfortably alone in the back row taking notes. Some in the audience knew I was tracking Susan's journey, and one of them -- a popular hell-raiser at meetings -- hollered out my name across the auditorium. I waved a notebook. "Do you believe her?" he asked. I said, "I do. I believe Susan because of her memories and because of the DNA evidence. And I am exploring the documentary record for support." This answer left much out -- in fact, one piece of evidence that Susan had just cited in her talk I no longer saw as evidence at all -- but it was not the right time for a nuanced answer. After a pause, the discussion moved on, leaving me to wonder what I really believed.

Later, Susan said, "David, when he asked you that question, I didn't know what you were going to say!" and I thought what a horrible position for Susan to be in -- years of effort on her part poured into a thoughtful, elegant presentation, her reputation suddenly hanging on the response of one stubborn soul who over many months had persistently refused to let words of full support issue from his lips. How horrible for her to be dangling like that. I felt at peace about my public support.

I did pay a price, though. Afterward, as I trekked across the Hannibal LaGrange college campus on my way to other lectures, I imagined conferees thinking, "There goes the dupe." At one point I asked Henry Sweets, the conference organizer and director of the Boyhood Home, if he knew of anything at all in the Hannibal collection that might shed light on Susan's beliefs. He laughed. "You mean, do we have Nina's teething ring? No, sorry." But I bore it. I knew Henry for a Susan booster.

However, not everyone at the conference was. Susan later told me of a woman who said to her after her talk, "I'm a zero percenter. I believe you zero percent." I wondered if this was the same woman who walked up to Deb Gosselin, who was also at the conference, and said, "I read your book." Pause. "Didn't believe it." And then she walked off. Deb told me the story with a laugh -- she always has a laugh ready -- over lunch the next day. I found her to be more hard-nosed about the evidence than Susan was but equally optimistic. She told me that Susan's goal from the very beginning was not to prove any connection to Samuel Clemens but rather to find her mother. She described it as a quest filled with hope but tinged with fear for what it might turn up. Susan had strong, loving memories of Elwood Bailey, even though she moved out of the household at age seven and saw little of him between then and his death less than two years later. Deb said, "If Susan ever discovered Elwood was not her father, it would kill her." I wondered if Susan had come to feel the same way about Nina as her mother.

A riverboat dinner cruise ended the conference, and I was lucky to end up at Henry Sweets's table as the boat chugged along where Huck and Tom once swam. Henry has directed the Boyhood Home for so many years that you can practically imagine him sleeping in the back bedroom along with Sam and his brother. At one point I asked him about his surname. He said the "s" on the end is unusual, and it has helped him trace his roots. It's a common African-American surname, and Henry, who is white, once almost attended a family reunion that was entirely African-American. His roots are in Kentucky. "So you descend from slave owners?" I asked. "Oh yes," he said with a frankness that seemed to acknowledge the institution as an undeniable part of every American's heritage.

Henry has fielded many a phone call from people claiming to be related to Mark Twain. He disabuses them, and he's probably good at it. He told us about one fellow with impossible dates: his grandfather babysat Samuel Clemens, he said, but, as Henry pointed out to him, his grandfather was born after Clemens. "I know what I was told," the man huffed. Another claimant published a book consisting of anagrams laboriously constructed from sentences in Mark Twain's books proving his kinship with the author. "He had way too much time on his hands," Henry said. I thought of the hundreds of hopefuls I had seen on genealogy message boards looking for evidence of shared ancestry with the great one, many of them bearing his surname. But as Deb once said, "If your name is Clemens, you're probably not related." If that fact were broadcast across the land, it could cut Henry's phone calls in half.

![]()

The DNA sources thus far raised and rejected -- hair, envelopes, dead bodies -- all theoretically could have yielded known Clemens or Langdon DNA for direct comparison with Susan's DNA. Although none of those ideas proved feasible, an indirect approach was possible, one that compared Susan's DNA with that of known living relatives of Samuel Clemens or Livy Langdon. This is the method that produced Susan and Deb's strongest prima facie evidence.

Here is how it works. After requesting a DNA kit from a popular genetic genealogy site like AncestryDNA or FamilyTreeDNA, you vigorously swab the inside of your cheeks or dribble saliva into a test tube, ship off your precious bodily fluid, and await the results of the examination of some 700,000 locations on your chromosomes. A month or so later, you receive a list of your "matches" -- real people, all of them alive at the time of saliva extraction (one hopes), all of them curious about their own lineage, and most of them related to you, either closely or remotely, by virtue of descent from a common ancestor.

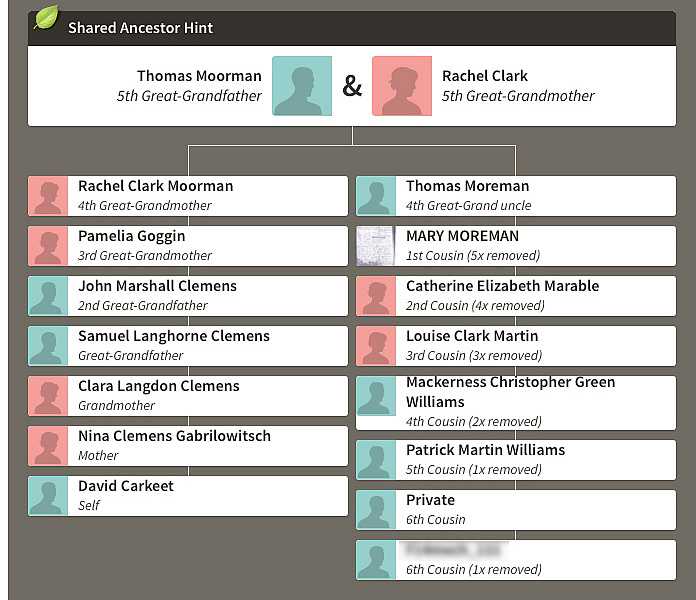

The trick is to nail down that ancestor. In October I decided to put off my final research trip (to Tampa) until I had studied the DNA evidence more closely. I asked Susan for the password to her account, and she gave it to me. When I began to explore her match results, they seized my attention as nothing had since I first heard the tale of the Tampa vanilla ice cream soda kidnapping.

Susan shows over 8,000 people on her match list. This in itself means nothing and is not unusual, but it must be reduced to a manageable horde. The first step is to construct a family tree based on all that one can learn about one's ancestry, and Ancestry.com, the umbrella site for AncestryDNA, provides the research tools: online records of births, deaths, marriages, and divorces, censuses, military records, passport applications, ship manifests, and more. Meanwhile, ideally most of your matches have been busy over the years constructing their family trees and, like you, posting them at Ancestry.com. Your soft-science tree construction puts AncestryDNA in a position to use its hard-science DNA test results to help you. The site relentlessly surveys your tree and all of your matches' trees, and when it spies a common surname with a common biography attached to it (birth date, birthplace, etc.), it sends you a "Shared Ancestor Hint" -- a mini-tree showing the two parallel lines of descent from the espied common ancestor. One line leads down to you, the other down to your match, and an accompanying label identifies your relationship: 6th cousin, 4th cousin once removed, etc.

I have simplified the process a bit. Sometimes AncestryDNA fails to give you a Shared Ancestor Hint because your match's tree building stopped short in the backwards march of time. But if a match's tree does not reach the common ancestor by a generation or two, it is often easy to fill in the gaps by using the site's research tools and by drawing information from other trees. There are some obstacles, though. Not all of one's matches build a tree. Also, people can introduce terrible errors into their trees. Finally, some matches build trees but choose to keep them private and inaccessible, even after polite emails inviting a pooling of information. We do not like any of these people.

Susan and Deb, drawing on Deb's many years of genealogical experience, constructed a 13-generation tree positing that Susan's biological parents were Elwood Bailey and Nina Gabrilowitsch. With that tree in place, they were able to find common ancestors of Susan and her matches on the Elwood Bailey line (happily confirming Susan's conviction that Elwood was her biological father) and on both the Clemens and Langdon lines. This is the evidence they present at the end of their book, in tables showing the common ancestors of 10 Bailey matches, 14 Langdon matches, and 13 Clemens matches. Later, thanks to further work by Susan and an ever-growing database (i.e. DNA submissions), the numbers grew to more than 60 matches on Samuel Clemens' line and 20 on Livy's, along with more than 60 matches on Elwood's line. (The comparatively small number of Langdon matches could reflect a number of factors: differences in family fecundity, the unpredictability of the chromosomal segments one inherits, and unequal degrees of genealogical enthusiasm among people at the tree bottoms. The DNA database, after all, is limited to those who submit samples, and a zealot who enlists relatives to submit test kits can cause the number of matches in a branch to swell.) Susan's relatives on these three lines range in degrees of separation from her: 3rd through 9th cousin (Bailey line), 4th through 10th (Clemens), and 6th through 11th (Langdon).

At first, as I looked at the DNA evidence closely, it seemed strange to see a tree asserting as fact the central point in dispute, namely that Susan descended from Elwood and Nina. But then I saw that the assertion was simply a hypothesis offered to explain the data of Susan's matches. After all, one cannot make sense of matches without putting forth a tree of some kind -- the matches would just sit there, inert. And as I examined match after match and saw how the overlaps in the DNA conformed to the posited descent, the hypothesis began to take on explanatory force, especially when set against the likeliest alternative tree showing Susan as the offspring of the couple who raised her in her early childhood, Elwood and Drucilla. That alternative hypothesis would leave unexplained the more than 80 total matches on the Clemens and Langdon lines.

What I found particularly stunning in Susan's match results was the breadth of distribution of the common ancestors: they were represented on not just one or two lines but on every major branch. Taking Samuel Clemens as an example and starting with the forks at the tree nodes occupied by his four grandparents, common ancestors to Susan's matches could be found back in time along all four of those lines. The same goes for the four lines up from Livy's grandparents and the four up from Elwood's.

Just as I finished my own work on Susan's matches, an expert signed on to help Susan and me interpret them. Jennifer Zinck is a professional genealogist who specializes in the intersection of traditional and genetic genealogy. She had already briefly consulted with Susan in June of 2014 and now returned to Susan's accounts at AncestryDNA and FamilyTreeDNA. At this point I wrote Jennifer and shared my sense of things, with emphasis on the points of the preceding paragraph, of which I was particularly proud. She wrote back to me, "While the methods that you (and she) are using are ok for some preliminary guesswork, they won't hold up." On the one hand, I felt crushed. On the other, I knew I was in the hands of an expert. I bided my time, awaiting her report.

While we wait, I should tell you about two complications. You may have noticed that thus far no mention has been made of the Gabrilowitsch line. Since Nina came from Clara and Ossip, if Susan came from Nina she should have matches in the Gabrilowitsch family tree. She does not, at least none that are discernible. But this surprised no one, at least not at first. Most of Ossip's living relations are overseas, and the AncestryDNA database has been limited to United States residents and has only recently expanded to the United Kingdom and Ireland. However, some years ago Mike Stern of Boston contacted a cousin of Ossip's living in Maryland, and, pursuing all things Gabrilowitsch, he elicited a DNA sample from him. Although the cousin had since died, the sample remained available for further tests, and last year Mike ordered one for purposes of comparison with Susan's DNA. A daughter of Nina would be a second cousin once removed to Mike's Gabrilowitsch test subject, and if Susan was such a daughter, there was a 90% chance or stronger that their names would pop up as matches to each other. But when the results came in, there was no match, to everyone's disappointment -- even Mike's. The failure did not disprove Susan's claim. But it certainly did not advance it.

The second complication was that in my own research at AncestryDNA I had come across several matches that seemed to undercut Susan's claim directly. They pointed to her biological descent from Drucilla, the woman Susan considered her stepmother. "Considered" is too weak a word. Bitter about the way Drucilla had treated her as a child, Susan was happy to learn that Drucilla was not her mother, initially when the family doctor told her that their blood types ruled it out, and later, when the DNA pointed to Nina as her mother. But Drucilla's blood type has never been documented. Since this door remained open, I browsed Drucilla's genealogy, which I found on a number of public trees at Ancestry.com. Seven of Susan's matches found places on Drucilla's tree quite easily -- five 4th cousins and two 3rd cousins to Susan if she was posited as Drucilla's daughter. I mentioned these to Jennifer and wondered what they could mean. Intermarriage among the various families? Hanky-panky? She said, "I've seen doozies" -- a preface of sorts, but to what? I would have to wait.

But not for long. By complete coincidence, sometime in December a new relative suddenly appeared on Susan's match list. This regularly happens as new DNA enters the database. What was striking was how close the new match was to Susan. His family tree showed that he and Susan, if she descended from Drucilla, had the same great-grandparents. In other words, he was Susan's second cousin, her closest match after years of testing. I was completely baffled. Susan could not have two mothers. The Clemens and Langdon matches pointed to Nina, and the new match pointed to Drucilla.

Jennifer saw the new match the same time as I did, and after a few days of further work, she told me in very clear terms what it meant. Susan's four maternal great-grandparents were definitely Drucilla's four grandparents. Susan's mother was therefore Drucilla or, if not Drucilla, then some other narrowly qualifying member of the family (a full-sibling sister of Drucilla's or a cousin of Drucilla's from her mother's full-sibling sister and her father's full-sibling brother). There was no doubt in Jennifer's mind. The facts had fallen into place very quickly. "I wish my own family were this easy," she said. (For those of you keeping score at home, the new second-cousin match showed 297 shared centimorgans across 20 DNA segments. And for those of you keeping very, very careful score at home, the higher than expected centimorgan number for a second cousin match is explained by a second line connecting Susan to this match, on which she is his second cousin once removed.) Jennifer said that other close matches showed without a doubt that Elwood was Susan's father, a proposition that was never seriously in doubt.

Through the research and writing of The Twain Shall Meet, co-author Deb Gosselin was always more guarded than Susan in committing to a conclusion. When Susan asked her what it would take to convince her fully, Deb replied, "Your European birth certificate or a DNA match to someone who descends from Elwood's or Nina's great-grandparents." No European birth certificate was ever located, but Deb's second criterion was met and even surpassed by a generation -- albeit in the negative. The key match turned out to descend not from great-grandparents belonging to Elwood and Nina, but from grandparents belonging to Elwood and Drucilla.

Jennifer's conclusion was based on Susan's matches of autosomal DNA. A mitochondrial DNA test would have required a living subject who had an ancestor in common with Susan, with both lines of descent along unbroken chains of women, and no such person had been found in the Clemens/Langdon/Elwood array of relations. Jennifer, however, found one in Drucilla's tree: a woman whose mitochondrial DNA results at the FamilyTreeDNA site showed her to be a third-cousin match to Susan. (This woman matches on Drucilla's maternal line whereas the second cousin identified via autosomal DNA was a match on both Drucilla's paternal and maternal lines.) The mitochondrial data supported the conclusion based on the autosomal matches.

![]()

When I received Jennifer's report, I didn't want to let go. What about all of Susan's Clemens and Langdon matches? "You can have ten thousand matches all over the planet," Jennifer said, "but they're irrelevant if you've got a second cousin match." I would have been uneasily content with this explanation, but when I shared the results with members of the Twain community, I got the same question back from several of them: What about Susan's matches with people in the Clemens and Langdon families? Don't they require explanation? What do they mean? I then asked myself if it was possible that they meant nothing. Perhaps the world was so small that people who are connected to us in one way can seem to be connected to us in another way. I decided that the best way to test the matches' significance was to try to recreate them under circumstances in which they were obviously insignificant.

For several months I had had my own Ancestry.com account, and on it I had constructed a feeble tree about my forebears. I decided to build a new, robust tree with a twist: I would be Nina's son. This new tree would be factual on my father's side, but I would replace my poor mother with Nina and build upward from there, drawing from a comprehensive Clemens/Langdon tree that Deb had sent me some time earlier. My father was almost exactly Nina's age -- not that he needed to be for the experiment, but it made the idea easier to swallow.

I started building. Ordinarily as one adds names to a tree, AncestryDNA will spy new connections and will generate new Shared Ancestor Hints. But as I created my fraudulent history, AncestryDNA fell silent, almost as if in rebuke. Whenever I checked, the only hints I saw were boring second cousins I was already familiar with on my father's side. I completed the tree as far back as I could, with some branches going back into the sixteenth century, but still no hints appeared. I was not surprised. After all, I was not Samuel Clemens's great-grandson, so why should my DNA matches align in such a way to suggest that I was?