Quotations | Newspaper

Articles | Special Features | Links | Search

SPECIAL FEATURE

by Barbara Schmidt

With special thanks

to Jeff Imparato and Donna Halper for assistance in locating original copies

of Harper's Weekly.

"Things a Scotsman Wants to Know" -

Mark Twain's Last Hoax?

"I always had an idea that most of the letters written to editors

were written by the editors themselves."

- Answers

to Correspondents," 10 June 1865

_____

First Publication

In 1973 the University of California Press published the Iowa-California edition of What Is Man? And Other Philosophical Writings edited by Paul Baender. The Iowa-California editions focused on providing scholarly and authoritative texts of Mark Twain's previously published works. However, Frederick Anderson, editor of the Mark Twain Papers, consented to the inclusion of a previously unpublished letter from Mark Twain to the editor of Harper's Weekly titled "Things a Scotsman Wants to Know," (pp. 398-400). Anderson and Baender felt the letter was closely tied in content and date of composition to a series of letters collected and first published in Letters from the Earth (1962) which were also included in the Iowa-California volume. Baender provided only minimal background information on "Things a Scotsman Wants to Know" dated August 31 [1909] and signed with a pseudonym "Beruth A. W. Kennedy." Baender noted that the letter was a reply to a previous inquiry in Harper's Weekly regarding theological questions which had been published a few weeks earlier.

According to biographer Albert Bigelow Paine, Mark Twain wrote very little for publication in 1909, but he did enjoy writing for his own amusement, "setting down the things that boiled, or bubbled, within him; mainly chapters on the inconsistencies of human deportment, human superstition and human creeds" (Paine, Letters, p. 833). Paine, in a very diplomatic manner, was referring to Mark Twain's diatribes against God and organized religion. Paine recalls, "One fancy which he followed in several forms (some of them not within the privilege of print) was that of an inquisitive little girl, Bessie, who pursues her mother with difficult questionings" (Paine, Bio. p. 1515). Mark Twain began the "Little Bessie" theological dialogues in February 1908 and continued reading and working with them in 1909 while he read them aloud to Paine.

"Things a Scotsman Wants to Know" was written at the end of August 1909. The polemic "Letters from the Earth," a collection of letters from Satan commenting on mankind, was written a few months later in October and November 1909. The same type of writing paper was used for both manuscripts. Passages from "Things a Scotsman Wants to Know" reverberate in "Letters from the Earth."

_____

Summer 1909 - Religious Controversies

In order to comprehend the full story behind "Things a Scotsman Wants to Know" it is necessary to study the religious controversies erupting across the United States in the summer of 1909 and consider the possibility that Mark Twain published additional commentary in Harper's Weekly on this same topic under more than one pseudonym.

_____

George Burman Foster in Chicago

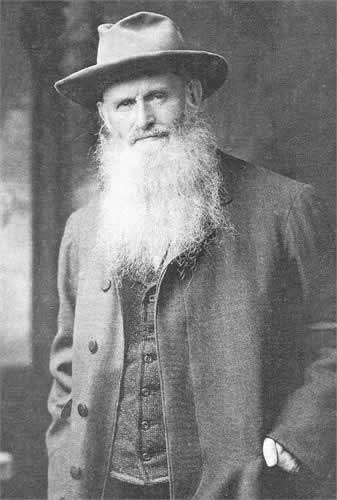

| A series of events in separate parts of the United States began in June 1909 that rocked the religious community and gave rise to the questions of whether or not Christian beliefs were undergoing radical change. The first controversy centered around Professor George Burman Foster (b. 1858 - d. 1918) of the University of Chicago. Foster, a Baptist minister, became one of the most influential theologians in his lifetime. Born in West Virginia in 1858., Foster graduated from West Virginia University and later studied at the Rochester Theological Seminary in New York. He later traveled abroad to Berlin, where he continued his theological studies. In 1895 he joined the faculty of the University of Chicago. Foster believed in a liberal interpretation of the Bible and when his book The Function of Religion in Man's Struggle for Existence was published in 1909 it generated a storm of debate with demands that he be ousted from the Baptist ministry and the University of Chicago. |  George Burman Foster from Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division |

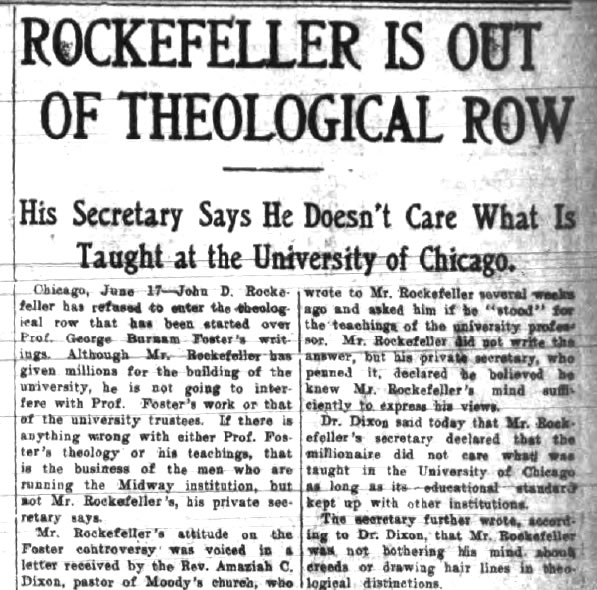

Baptist opponents criticized Foster for denying Christ's divinity and referring to a strict interpretation of the Bible as naive. Foster proposed that miracles were the refuge of ignorance and that modern techniques must take the place of magic. Foster believed that man had created God in his own image and not vice versa. The Baptist battle with Foster was played out in newspapers across the country. When opponents of Foster tried to drag John D. Rockefeller, a prominent Baptist who had given millions for building the University of Chicago, Rockefeller's secretary sent a reply indicating Rockefeller would not engage in theological hair splitting. Rockefeller's refusal to get involved led to even further criticism of Rockefeller's own Baptist minister in New York, Charles F. Akid..

Headlines regarding the Foster controversy appeared nationwide. The following are samples from newspapers in New York.

The New York Times, June 8, 1909 |

The New York Times, June 22, 1909 |

Front page of the Geneva (NY) Daily Times, June 17, 1909 featuring a story on the Rockefeller comment:

While the Baptist Chicago Minister's Conference did manage to expel Foster from their organization, he remained a member of the Baptist church and continued to hold his position as a professor of philosophy of religion at the University of Chicago until his death on December 22, 1918.

_____

Archibald Black, John Ewing Steen, and George Ashmore Fitch in New York

Archibald Black (b. 1877) |

John Ewing Steen (b. 1881 - d. 1955) passport photo |

George Ashmore Fitch (b. 1883 - d. 1979) passport photo |

At the same time the Baptist theologians were in an uproar over the writings of George Burman Foster, the Presbyterians in New York were facing their own upheaval. On June 14, 1909, three young graduates of Union Theological Seminary in New York City were licensed to preach in spite of their liberal interpretation of the Bible and beliefs that ran contrary to orthodox Presbyterian tenets. Archibald Black, born in Scotland in 1877, was the brother of Hugh Black who was chairman of Practical Theology at Union Theological Seminary in New York. John Ewing Steen, born in Pennsylvania in 1881, held degrees from Princeton University and was from a family of Presbyterian ministers. George Ashmore Fitch was born in China in 1883, the son of Presbyterian missionaries, and held a degree from the College of Wooster in Ohio. The Presbytery of New York, in split decisions, approved the licensing of the three young men following lengthy cross examinations. The decision left many of the more conservative committee members in tears. Black, Steen and Fitch professed beliefs that doubted the traditional Biblical version of Adam and Eve, the divine birth of Christ, and the literal interpretation of Christ's resurrection. The licensing of the three to preach was described in The New York Times as "one of the epoch making events in the history of the Presbyterian Church in America" ("Doubt Adam and Eve But They May Preach," The New York Times, 15 June 1909). The event stirred headlines in newspapers across the country.

Headlines from Denver Post, June 15, 1909, p. 4 |

Watertown (NY) Daily Times, June 16, 1909, p. 1 |

_____

"A chief interest for at least one summer"

According to biographer Albert Bigelow Paine, one of Mark Twain's favorite books that summer was Andrew Dickson White's A History of the Warfare of Science with Theology in Christendom -- a two volume set published by Appleton and Company in 1901 that he had owned since 1902. Paine recalls that on June 21, 1909 Mark Twain referred to Dickson's book saying, "When you read it you see how those old theologians never reasoned at all" (Paine, p. Bio. 1506). Paine referred to the book as "a chief interest for at least one summer" (Paine, Bio. p. 1539). Twain's personal copy of White's two volumes are heavily marked with his marginalia including a reference to the fact that "Amherst lately refused the missionary-ticket to two young candidates who doubted that all the B.C. pagans are roasting in hell" (Gribben, p. 760). (A search for news stories related to an Amherst controversy has failed to find additional information.)

_____

Harper's Weekly Publishes a Commentary

Edited by Col. George B. M. Harvey, Harper's Weekly published a commentary on the religious upheavals that summer titled "What Is Orthodoxy?" on July 3, 1909 (p. 5). The editorial was copied in newspapers around the country.

|

Harper's

Weekly,

July 3, 1909, p. 5. It begins to look as if the dictionary-makers would have to frame a new definition for orthodoxy before long. A few weeks ago the Chicago Baptists refused to turn down Professor Foster in the face of his repudiation of the authority of the Scriptures and his denial of the deity of Christ, and now the Presbytery of New York admits to the pulpit young Mr. Black, of Edinburgh, who accepts the story of Adam and Eve only as a figure, "not in its literal sense," acknowledges the divinity of Christ but not the virgin birth, and does "not believe in the flesh and blood resurrection." Substantially, as we make them out both Professor Foster and Mr. Black subscribe to the Unitarian theory, and it is not so long ago that Unitarians were denied admission to Baptist and Presbyterian pulpits on the ground that their faith was not that of Christianity. Whither we are now drifting is difficult to determine, but that the current is strong and rapid is certain. The Rev. Amaziah C. Dixon tried to draw out Mr. John D. Rockefeller apropos of the Foster episode, but received no more than a sentence from a secretary to the effect that "Mr. Rockefeller is not bothering his mind about creeds or drawing hair-lines in theological discussions." |

The publication of "What is Orthodoxy" in Harper's Weekly provided fuel for letters to the editor. At least one, which was never published in his lifetime, was written by Mark Twain using the pseudonym Beruth A. W. Kennedy. The entire sequence of correspondence that was published on the topic merits closer scrutiny.

_____

"Donald Ross" Asks Some Questions

Prior to July 1909, Mark Twain's previous contribution to Harper's Weekly that year had been a short essay titled "The New Planet" in the January 30, 1909 issue. "The New Planet" was a response to the announcement that Harvard astronomers had observed "perturbations" in the planet Neptune which indicated the presence of a new planet in the solar system. Astronomy and religion were two of Mark Twain's favorite topics and newsworthy events in either field were likely to ignite his interest.

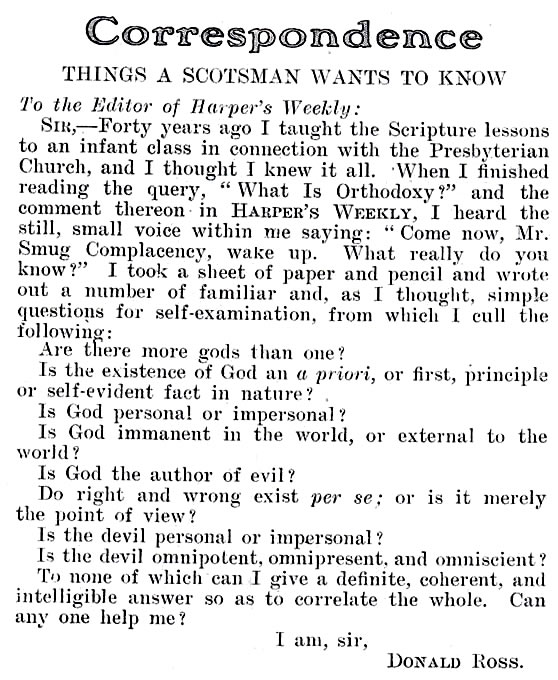

On July 24, 1909, (p. 6), Harper's Weekly published the following letter signed Donald Ross which included no date or indication of the author's residence:.

Without any additional clues to Donald Ross's identity, it is impossible to positively identify him. In this letter Donald Ross does not identify himself as a Scotsman. The question of whether or not Ross provided the headline "Things a Scotsman Want to Know" in his manuscript or whether Harper's Weekly editor George Harvey provided the headline is open to speculation. The Presbyterian denomination had originated in Scotland but it seems unlikely Harvey would have provided the headline based on a writer simply identifying himself as Presbyterian. The United States censuses for both 1900 and 1910 provide the names of at least four men named Donald Ross who were born in Scotland between 1830 and 1850 living in the United States at the time the letter was written. The time frames for their birthdates make them potential candidates to have taught a Sunday school class "forty years ago." The use of the name Donald Ross without an associated address protects the identity of all the possible candidates.

Did Mark Twain Write the Donald Ross Letter?

Mark Twain frequently mentioned his Presbyterian background in his writings. In a letter he wrote from St. Louis, Missouri to the San Francisco Alta California published May 19, 1867 he described addressing a children's Sunday school class: