Appreciation and Introduction

|

Volumes 17 and 18 of the Gabriel Wells Definitive Edition of Mark Twain's works are parts 1 and 2 of Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc. The Appreciation was written by Henry Van Dyke, a Presbyterian clergyman, writer, educator and personal friend of Samuel Clemens. Born in Pennsylvania in 1852, Van Dyke lived most of his life in New York. He attended Brooklyn Polytechnic Institute, Princeton Theological Seminary, and studied for a time in Berlin. He became an ordained Presbyterian minister in 1879. Van Dyke established a solid reputation as a cleric and a writer. In 1899 he was invited to become Professor of English Literature at Princeton and remained in that position until 1923 with leaves of absences for diplomatic missions abroad. Clemens owned a number of Van Dyke's books and wrote, "I greatly admire his literary style -- this notwithstanding the drawback that a good deal of his literary product is of a religious sort." |

Henry Van Dyke (b. 1852 - d. 1933) |

|

AN APPRECIATION AMONG all his books, the one which Mark Twain liked best, and in which he took the most sure satisfaction, was Joan of Arc. One reason that he gave for this was because he had worked twelve years on it, ten of preparation and two of writing, and thus it had given him "seven times the pleasure afforded by any others." But there was another and a deeper reason. Almost every really great humorist has a vein of romantic sentiment in his nature. That is what keeps him from sinking into the bitter satirist. Mark Twain had two strong devotions; you might almost call them adorations. The first was for the Christian womanhood of his own wife; the second was for the unselfish heroism of the Maid of France. To the first devotion he bore silent witness by a tender, life long service to one who had done him "good and not evil all the days of her life." I like to think how he would have manhandled the person who dared to insinuate that her gentle influence was a hindrance in his career. To the second devotion he erected the beautiful shrine of this book. It is wrought with loving care, on a design which, so far as I know, was original with him, at least in dealing with this subject. It professes to be a personal memoir of the peasant girl of Domremy who became the Deliverer of France, written by one Louis de Conte, who was the playmate of her childhood and afterward her secretary and the companion of her brief, glorious career up to the day of her fiery martyrdom. 'Tis a simple artifice, but it enables the author to sink himself in his work, just as the Japanese say their greatest painter disappeared into one of his own pictures. Yet another veil Mark Twain interposed between his fame as a humorist and his beloved book. He first published the chapters in Harper's Magazine as a translation by one "Jean Francois Alden." This name no doubt was a tribute of affection to the editor whom we all loved, Henry Mills Alden. But no disguise could effectively hide the hand of Mark Twain in the story. Here are his directness and force; his irrepressible humor, as in the scenes where the fat braggart called "the Paladin" takes part; his penetrating simplicity in the point of view; and above all his essential chivalry of heart, the same that blazed out in his white-hot essay, "In Defense of Harriet Shelley." The scholarship of the book is sufficient, though not meticulous. Of course there are mental anachronisms in it. No Louis de Conte of the fifteenth century could ever have written it. Mark Twain -- or perhaps Tom Sawyer ripened --was the only man who could have done it. I have read most of the famous books about Jeanne d'Arc -- Quicherat, Michelet, Anatole France, Andrew Lang, Gabriel Hanotaux, the poetic dramas of John Skrine and Percy Mackaye -- and I think our own Joan of Arc will stand up well beside the best of them in vitality, human truthfulness, and poignant, tragic interest. This interest is ten times deepened since the Great War, in which the spirit of the Maid seemed to return lo help France save the world, even as she had saved France four centuries ago. That French soldiers had visions of her, I do not doubt. If you wish to know Mark Twain at heart, the very best of him -- you will read his Joan of Arc.

|

An Introduction by Albert Bigelow Paine follows the Appreciation.

|

INTRODUCTION IN January, 1906, the writer was present at a dinner given to Mark Twain at the Players Club in New York City. It proved rather an important dinner, as it turned out, but that is another story. Only one incident of it is pertinent here. When the food courses and coffee had been served, and the guests were drifting about in general conversation, I took occasion to mention to Mr. Clemens my great admiration for his story, Joan of Arc. He said: "Yes, it is my favorite among the books I have written. In a way it has been a part of my whole life. It had its beginning when I was a printer's apprentice in Hannibal. One day I saw a piece of paper blown along the street by the wind, and when I picked it up, it proved to be a page out of some simple old history of Joan's career. I took it home and read it. It was from her life in prison, in the cage at Rouen. Two ruffian English soldiers had stolen her clothes, and she was reproaching them and enduring their ribald replies. It roused all my indignation; and my sympathy for Joan and my interest in her continued to grow from that moment. I had never been a reader of books, but from that time I read every history I could get hold of. I am glad I found that old piece of paper." It was, in fact, the turning-point in Mark Twain's life. His career as a man of letters began there, though it was a long time before he would enter upon the trade of authorship, and it was not until thirty years later that he seriously considered writing the story of Joan of Arc. It was about 1880 that he first contemplated the work and began collecting material -- that is to say, books on the subject. He appears, however, not to have done any actual writing at this time. Perhaps he felt that he was not yet qualified, and then he was very busy with many investments and business undertakings. At all events, he waited until the late summer of 1892, when, at Florence, Italy, in the beautiful Villa Viviani, he sat down to tell the story that had meant so much to him so long. He said once that he began the story five times, but none of the discarded beginnings exist to-day. They were wisely put aside, no doubt, for no story of the Maid could begin more delightfully than the one supposedly told in his old age by Joan's secretary, the Sieur Louis de Conte, who had followed with her from childhood to martyrdom. Mark Twain's reverence for his subject was so great that from the first he contemplated printing it anonymously, fearing it would otherwise be misunderstood. He felt that The Prince and the Pauper had missed a certain appreciation by being connected with his signature, and he resolved that its companion piece (as he then regarded Joan) should be accepted on its merits and without prejudice. Walking the floor one day at Viviani, he said to Mrs. Clemens and their daughter, Susy: "I shall never be accepted seriously over my own signature. People always want to laugh over what I write, and are disappointed if they don't find a joke in it. This is to be a serious book. It means more to me than anything I have ever undertaken. I shall write it anonymously." So it was that as the old Sieur de Conte he took up the pen in that lovely spot which, of all others, seems now the proper environment for the story's telling. He worked rapidly, though some of his authorities were French, and, while he had a fair reading-knowledge of the language, the translation and sifting must have required time. Indeed, the multitude of notes along the margin of his French authorities bear witness to the magnitude of his toil. Yet he was full of his subject; the reading of his youth and manhood had made it very real to him, and the story he told was almost as something he had lived; the personality of the fictitious de Conte is vividly realized because it was so true to Mark Twain. By February, '93, he had completed the first part of Joan's career -- about two hundred thousand words, bringing his tale to the triumphant entry into Orleans. He had half a mind to end the story there, so sorrowful was the tragedy ahead. He did, in fact, put the manuscript aside, and on his next trip to America offered it to Mr. Alden for Harper's Magazine. It was Mr. Alden's wish that the tale be continued. To the author he wrote:

This was in July, 1894. Clemens already had decided to finish the book, and Mr. Alden's letter no doubt strengthened his purpose. He returned to Europe, and at Etretat, a watering-place on the French coast, took tip the tragic history, and was soon absorbed in it. "It is a tale that writes itself," he said in a letter to his friend H. H. Rogers. "I merely have to hold the pen." He spent some weeks in Rouen, on the way from Etretat to Paris, where they leased for the winter the studio home of the artist Pomeroy, 169 Rue de la University, a lovely retreat beyond the Seine. Here the story of Joan was brought to an end. Each evening Clemens read the chapters of the day to the family circle. Those that told of the trial of the frail martyr wrung their hearts. Susy Clemens would say, '' Wait-wait till I get a handkerchief!'' and one night, when the last pages had been written and read, and Joan had made the supreme expiation for devotion to a paltry king, Susy wrote in her diary, "To-night Joan of Arc was burned at the stake" -- meaning that the book was finished. This was at the end of January, 1895. Mark Twain made his lecture-tour around the world that year and the next, and the story appeared serially in Harper's Magazine during his absence. It was printed without his signature, but the work was presently recognized as being from his hand. There were phrases which no one but Mark Twain could have written. It was decided, therefore, to publish the book without further attempt at concealment. It seems curious to-day that any one could have regarded this lovely human history with doubtful appreciation. But then most readers had never been taught before to regard Joan as a human being. It was not at first easy to realize that this is just the very wonder of Mark Twain's Joan. She is a saint; she is rare, she is all that is lovely, and she is a human being besides. Considered from every point of view, the Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc is Mark Twain's supreme literary expression -- the loftiest, the most delicate, the most luminous example of his work. It is so from the first word of its beginning -- that wonderful "Translator's Preface," to the last word of the last chapter, where he declares that the figure of Joan, with the martyr's crown upon her head, shall stand for patriotism for all time. Indeed, it seems incredible to-day that any reader, no matter what his preconceived notions of the writer or of Joan may have been, could have followed these chapters without realizing that this was a book such as had not before been written. Let any one who read it then and doubted, reread and reconsider it now. A surprise will await him, and it will be worth while. He will know the true personality of Joan of Arc more truly than ever before, and he will love her as the author loved her, for "the most innocent, the most lovely, the most adorable child the ages have produced." Mark Twain's love of Joan was a beautiful and a sacred thing. He adored young maidenhood and nobility of character; he was always the champion of the weak and the oppressed. The combination of these characteristics made him the ideal historian of an individual and of a career like hers. It seems fitting that in his advanced age (he was nearing sixty when it was finished) he should have written this exquisite story. He could not have written it at an earlier time. It had taken him all the years to prepare for it; to become softened; to acquire the delicacy of expression, the refinement necessary to the achievement. Mark

Twain's story of Joan is no longer misunderstood. The public that

always renders justice in the end has demanded more copies of it each

year since its publication. To-day it ranks in popularity with the

books that found a quicker appreciation. Its author lived long enough

to see this change and to be comforted by it, for, though the creative

enthusiasm in his other books soon passed, his glory in the tale of

Joan never died. On his seventy-third birthday, when all of his important

books were far behind him and he could judge them without prejudice,

he wrote as his final verdict:

ALBERT BIGELOW PAINE. |

Dividing the Work

Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc is divided into

two volumes in the Gabriel Wells Definitive Edition. The division is the same

that was used in the 1899

uniform editions issued by American Publishing Company. Volume 17 concludes

with Chapter 27 in the middle of the section known as Book II. Volume 18 begins

in the middle of the section known as Book II with Chapter 28.

Combining Illustrations

Almost ten years after the publication of Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc, the December 1904 issue of Harper's Magazine featured an essay by Mark Twain titled "Saint Joan of Arc." The essay featured four full-page color illustrations by Howard Pyle.

Howard Pyle (b. 1853 - d. 1911) |

Howard Pyle was a native of Wilmington, Delaware. After studying art briefly in Philadelphia, Pyle relocated to New York By the late 1870s his work was being featured in leading New York periodicals including Harper's publications. In the 1880s Pyle moved back to Philadelphia where he published and illustrated his own The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood. It was one of a number of books Pyle would write and illustrate and was a favorite of Clemens who owned or gave away at least three copies. Clemens's friend George Washington Cable wrote of seeing the family read aloud from "Howard Pyle's beautiful new version of Robin Hood. Mark enjoys it hugely" (Gribben, p. 563). Pyle would eventually produce over three thousand illustrations for magazines and books in his lifetime, specializing in images of fairy tales and legends including those of King Arthur's court. |

The Gabriel Wells Definitive Edition of Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc utilizes two of Pyle's illustrations (reprinted in black and white) from the December 1904 Harper's Monthly essay titled "Saint Joan of Arc." In addition, illustrations from Frank Vincent Du Mond that had been used in the 1899 uniform edition of the work from American Publishing Company were also reused. Also featured are works from French artists Jules Eugene Lenepveu (b. 1819 - d. 1898) and Jean-Jacques Scherrer (b. 1855 - d. 1916).

Illustration List for Volume 17

The frontispiece for Volume 17 is from the painting by Jules Eugene Lenepvue. It had not appeared in either the first edition or any previous uniform editions of the book. It was reprinted in black and white. |

Illustration List for Volume 18

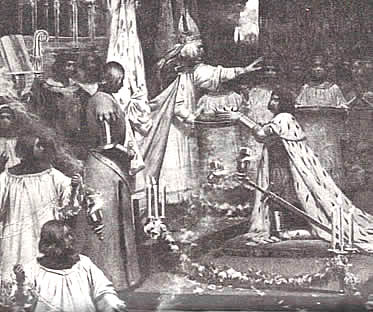

Du Mond's version of "The Coronation of the French King at Rheims" from the 1896 first edition was replaced by a similar version of the same scene by Jules Eugene Lenepveu. |

"The Coronation of Charles VII at Rheims" based on Lenepveu's painting had not appeared in any previous edition. It was reprinted in black and white. |

Full Text Online Availability Via Archive.Org

Volume

17

Volume

18

_____

Dearinger, David Bernard. Paintings and Sculpture in the Collection of the National Academy. (National Academy of Design, 2004).

"Dr. Henry Van Dyke Dies in 81st Year," The New York Times, 11 April 1933, p. 19.

Gribben, Alan. Mark Twain's Library: A Reconstruction. (G. K. Hall, 1980).

"Howard Pyle Dies in Italy," The New York Times, 10 November 1911.

Rasmussen, R. Kent. Critical Companion to Mark Twain: A Literary Reference to His Life and Work. (Facts on File, 2007).

Twain, Mark. "Dr. Van Dyke as a Man and as a Fisherman." Reprinted in Who Is Mark Twain? (University of California Press, 2009).