Introduction

Volume 28 of the Gabriel Wells Definitive Edition of Mark Twain's works is Mark Twain's Speeches as compiled and edited by Albert Bigelow Paine. Harper and Brothers had originally issued a volume of Mark Twain's Speeches in July 1910 in their Uniform Library Edition with red cloth and gold cornstalk bindings. The 1910 edition was compiled by Harper and Brothers bookkeeper Frederick A. Nast and featured 104 speeches, a frontispiece portrait of Clemens, an introduction by his close friend and literary advisor William Dean Howells (b. 1837 - d. 1920) and a preface that Clemens had written for an English edition of Mark Twain's Sketches. Although the 1910 collection received mostly positive reviews it was criticized for not presenting the speeches in chronological order.

In 1923 Albert Bigelow Paine revised the collection of speeches. Paine's edition was copyrighted by Harper and Brothers in May 1923 and released in their red cloth and gold cornstalk Uniform Library Edition binding. The 1923 edition contains only 84 speeches -- 18 of which had not been included in the 1910 edition. Paine also deleted 36 speeches that had appeared in the 1910 edition. While there is overlapping contents among both versions, neither the 1910 or the 1923 edition approaches being a comprehensive collection of Mark Twain's known speeches.The existence of two separate and non-identical volumes of Mark Twain's Speeches in similar bindings is often a source of confusion for book collectors. The 1923 edition of Mark Twain's Speeches is Volume 28 of the Gabriel Wells Definitive Edition.

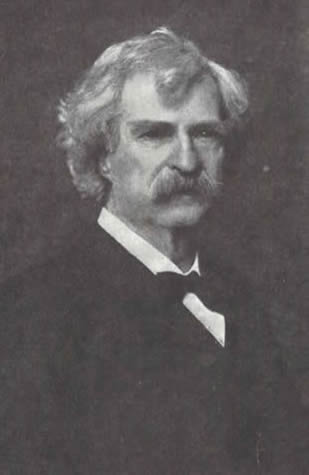

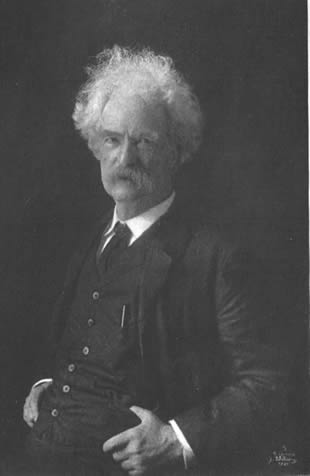

The 1910 and 1923 editions of Mark Twain's Speeches feature different frontispieces.

Frontispiece from Harper's 1910 edition of Mark Twain's Speeches |

Frontispiece for 1923 Gabriel Wells edition of Mark Twain's Speeches from a 1904 photo by J. G. Gessford |

The 1923 edition of Mark Twain's Speeches retains William

Dean Howells's introduction that had originally appeared in the 1910 edition.

The introduction refers to Clemens in the past tense, indicating it was written

shortly after Clemens had died in April 1910. In the Gabriel Wells Definitive

Edition, Howells's introduction is retitled and appears as "An Appreciation"

without any further revision. Howells died in May 1920, three years prior

to publication of Paine's edition of Mark Twain's Speeches. The facsimile

of his signature that appears at the end of "An Appreciation" did

not appear in the 1910 edition and may have been obtained from an earlier

and unrelated document. The facsimile signature was probably added by Paine

in order that all of the appreciations in the Gabriel Wells edition include

the signatures of their contributors.

|

AN APPRECIATION THESE speeches will address themselves to the minds and hearts of those who read them, but not with the effect they had with those who heard them; Clemens himself would have said, not with half the effect. I have noted elsewhere how he always held that the actor doubled the value of the author's words; and he was a great actor as well as a great author. He was a most consummate actor, with this difference from other actors, that he was the first to know the thoughts and invent the fancies to which his voice and action gave the color of life. Representation is the art of other actors; his art was creative as well as representative; it was nothing at second hand. I never heard Clemens speak when I thought he had quite failed; some burst or spurt redeemed him when he seemed flagging short of the goal, and, whoever else was in the running, he came in ahead. His near-failures were the error of a rare trust to the spontaneity in which other speakers confide, or are believed to confide, when they are on their feet. He knew that from the beginning of oratory the orator's spontaneity was for the silence and solitude of the closet where he mused his words to an imagined audience; that this was the use of orators from Demosthenes and Cicero up and down. He studied every word and syllable, and memorized them by a system of mnemonics peculiar to himself, consisting of an arbitrary arrangement of things on a table -- knives, forks, salt cellars; inkstands, pens, boxes, or whatever was at hand -- which stood for points and clauses and climaxes, and were at once indelible diction and constant suggestion. He studied every tone and every gesture, and he forecast the result with the real audience from its result with that imagined audience. Therefore, it was beautiful to see him and to hear him; he rejoiced In the pleasure he gave and the blows of surprise which he dealt; and because he had his end in mind, lie knew when to stop. I have been talking of his method and manner; the matter the reader has here before him; and it is good matter, glad, honest, kind, just.

|

An Introduction by Albert Bigelow Paine follows the Appreciation.

|

INTRODUCTION MARK TWAIN made his first speech when he was about twenty years old, at a printers' "banquet," in Keokuk, Iowa. No fragment of this early effort has survived the years, but his hearers long recalled it as a hilarious performance which promptly qualified him for membership in a debating society, where he became the chief star. Doubtless he spoke on other festival occasions of the moment, and one wishes that some slight remnant of those beginnings might have been preserved. Keokuk was a brief incident in Mark Twain's career. He was presently piloting on the Mississippi River, where he was much regarded as a story-teller by his associates, but if he ever spoke at a pilots' dinner or at one of their meetings no record of the is discoverable. It was not until he had left the river several years behind him and had become a sage-brush journalist, reporting the Nevada legislature, that we learn of another public appearance, this time as Governor of the Third House, a burlesque organization to which he delivered in person his first (and last) "annual message." The Third House threw open its doors to the public for the event, levying a tax of a dollar on each admission, for the benefit of the church. Very likely this was Mark Twain's first appearance before a mixed audience, and if the memory of those present may be trusted his speech that night was the "greatest effort of his life." Such a verdict is to be taken with a liberal allowance for the enthusiasm and setting of the occasion, and while we may regret that no sample of that celebrated address has come down to us, we may console ourselves in the thought that perhaps it is just as well for its renown that this is so. Mark Twain had at this time written very little that would bear the test of years, and it seems probable that his memorable message was for that day and date only. But now came a change -- a large and important change -- in Mark Twain's intellectual life. One might call it a "sea change," for it followed a trip to the Sandwich Islands, where he had remained for a period of four months, a considerable portion of that time in almost daily intercourse with America's distinguished statesman, Anson Burlingame, who had stopped there on his way to China. Burlingame's example, companionship, and advice, coming when it did, were in the nature of a revelation to Samuel Clemens, who returned to San Francisco, consciously or not, the inhabitant of a new domain. His Sandwich Island letters to the Sacramento Union had been nothing remarkable, but the lecture he was persuaded to deliver a few months after his return indicates a mental awakening, a growth in vigor and poetic utterance that cannot be measured by comparison with his earlier writings because it is not of the same realm. Fortunately, some considerable portions of this first lecture have been preserved, and the reader may judge for himself what the Mark Twain of that day -- he was then thirty-one -- had to say when, as he tells us, he appeared, "quaking in every limb," the fear of failure in his heart. The story of that evening, as set down in Roughing It, is very good history, and need not be repeated here. He subsequently delivered the lecture the length of the Pacific coast, and finally at Cooper Union in New York, just before sailing on the Quaker City Holy Land excursion. The result of the Quaker City venture was a series of travel letters of quite a new sort, and Mark Twain returned to find himself famous. Temporarily in Washington, he was all at once in the midst of receptions and dinners and much in demand as a speech-maker. One example only of that time has survived -- his reply to the toast of "Woman" at a banquet of the "Washington Correspondents' Club." It does not seem particularly brilliant, as we read it to-day, but it must have been so regarded at the moment, for no less an authority than Vice-President Schuyler Colfax pronounced it, "the best after-dinner speech ever made." Doubtless it was a refreshing departure from the prosy or clumsy-witted efforts common to that period. It is not the purpose here to set down a history of Mark Twain's speech-making career. He was fully launched, now, and the end would not come until the final years of his life, his prestige and popularity steadily growing until in those later days he occupied a position which none thought even to approach. It may be worth while, however, to record something of his methods of preparation and delivery. In the beginning he carefully wrote out his speeches, learned them by heart, and practiced them in the seclusion of his chamber. Later on he frequently trusted himself to speak without any special preparation or notes, confident of picking up an idea from the toastmaster's introduction or from some previous speaker, usually asking to be placed third on the list. But if the occasion was an important one he wrote his speech and rehearsed it in the old way. His manner of delivery did not change with the years, except to become more finished, and to seem less so, for it was his naturalness, his apparent lack of all art, that was his greatest charm. One of those who attended his earliest lectures spoke of his exaggerated drawl of that day, his habit of loosely lounging about the stage, his apparent indifference to the audience. His later art was of the sort that made the hearer forget that he was not being personally entertained by a new and wonderful friend, who had come there for his particular benefit. One listener has written that he sat "simmering with laughter" through what he thought was a sort of introduction, waiting for the traditional lecture to begin, when presently with a bow the lecturer disappeared and it was over. The listener looked at his watch -- he had been there for more than an hour. His manner gave the impression of being entirely unstudied, yet no one better than Mark Twain knew the value of every gesture and particularly of every pause. He used to say, "The right word may be effective, but no word was ever as effective as a rightly timed pause." In his speech on "Speech-making Reform," with which this volume opens, he has given us, in semi-burlesque, a summary of his own methods. Mark Twain's speeches, as here collected, are rather loosely separated into three periods: the first division beginning with his San Francisco lecture, continuing through those years when his conquest of the world of letters had not yet lost its novelty, when his blood was quick, when the gods were still kind and his words in the main a lilt of good-natured foolery. The middle period covers those years when the affairs of men and nations began to make a larger appeal, when political abuses and the injustice of class began to stir him to active rebellion and to righteous, even if violent, attitudes of reform. The final group is of those later days when, full of honors yet saddened by bereavement and the uncertainty of life's adventures, he had become the philosopher and sage whose voice was sought on every public question, whose humor was more gentle, whose judgments had become mellowed and were all the more welcome for that reason. The conclusion of the Seventieth Birthday address and of the Liverpool speech are perhaps the most perfect examples of his after-dinner art.* Not to have heard Mark Twain is to have missed much of the value of his utterance. He had immeasurable magnetism and charm, his face, surrounded by its great mass of hair, pure white in old age, was one of unusual beauty, having in repose that gravity and pathos of which his whimsical humor and flickering smile were the break. No one could resist him- probably nobody ever tried to do so. _____ *

The closing paragraphs of the Liverpool speech were repeated at the

end of a speech made at the Lotos Club, N. Y., January 11, 1908, and

will be found so placed in this volume. ALBERT BIGELOW PAINE. |

Illustration List for Volume 28

|

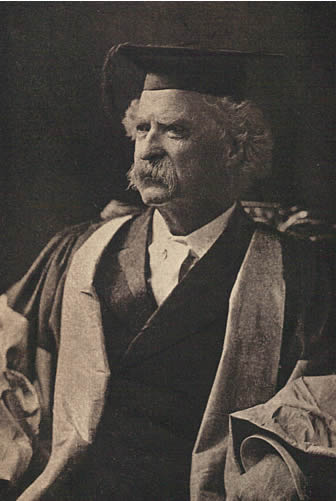

Volume 28 of the Gabriel Wells Definitive Edition contains four photographs.

|

Mark Twain as Doctor of Letters, University of Oxford, 1907 from the Gabriel Wells Definitive Edition |

_____

Budd, Louis J., ed. Mark Twain: The Contemporary Reviews. (Cambridge University Press, 1999).

Johnson, Merle. A Bibliography of the Works of Mark Twain. (Harper and Brothers, 1935).

Rasmussen, R. Kent. Critical Companion to Mark Twain: A Literary Reference to His Life and Work, Volumes 1 and 2. (Facts on File, 2007).