BATTLESHIPS AND SOCIETY

|

|

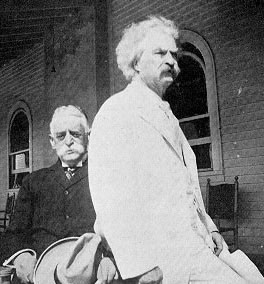

The Chaplain's cousin.

|

ONE day three English cruisers came into the harbor. The next evening Mr. Clemens received a charming letter from the Chaplain of one of them, a letter which pleased him much because of its quaint phrasing. Here it is, in part:

Dear Doctor Clemens: I understand we are cousins and in a closer sense than that you are American and I English. Your dear mother is sister to my (to me) dearer mother!

I am jealous that my Alma Mater was forestalled by Oxford in adopting you.

I regret, also, that the exigencies of the service prevented my being in Oxford -- in fact, England -- to assist those who desired to do you honor. Think you that we might square yards in some way? May I suggest a way? What if you did us the honour to lunch on board the battleship on Monday or Tuesday? Does that appeal to your sense of humour? If not, will you let it touch that whole-hearted generosity of yours, and come?

We won't ask you to say anything funny, but will, if you will honour us, show you as much of the ship as you might wish to see, and do our best not to bore you too much. I have a confession to make -- my conscience compels me. Here it is -- Fleet-Surgeon F_____ and I made a pilgrimage yesterday to your present shrine to do you homage. We had one golden opportunity, when you were smoking your after breakfast cigar on the terrace of the hotel, but being the shyest o£ a shy race or let me say, the kindest of our kind, we refrained from taking advantage of your only moment of isolation to attack you and achieve the object of our visit.

The letter went on to name days and hours when Mr. Clemens might favor them, and wound up with:

I must apologize for the length of this invitation. My excuse is, that it is not so much an invitation as a humble petition from two GRATEFUL ADMIRERS-IN-CHIEF.

Of course Mr. Clemens went, and had a beautiful time, and made a speech that made them rock with laughter and then furtively wipe away tears. The Chaplain told us about it afterwards. That is the way we knew. And Mr. Clemens also told the Chaplain about his friends, so that a boat was sent for us and we had afternoon tea on board. The Chaplain had a hospitable soul, as well as a graceful pen and the happy gift of speech, so that he made a royal good host. We saw the six hundred men of the battleship stand up in straight military lines on the forward deck and answer to roll-call. Then the shore-leave men scrambled down into their boats, held up their oars in perfect vertical lines, dropped them at the word of command, and rowed off cheerily, to have a respectable British orgy in the staid town of the island.

Then we, in our turn, scrambled down to our boat, the crew gave a cheer for Mr. Clemens, and as the launch moved away we waved lingering farewells to the old grey cruiser. Almost all social functions, and there were many on the little island, Mr. Clemens escaped. Once in a while he was persuaded to go to an afternoon tea. These were very popular. On these occasions innumerable kinds of rich cake were served, in such reckless profusion and with such pressing hospitality that dinner was completely wrecked. But when we were all invited to a West-Indian Pepper-Pot luncheon, we eagerly accepted. Our hostess was not a born islander, but as fourteen or fifteen winters had sheltered her on the Happy Isles, she was an adopted daughter. Besides, she knew how Pepper-Pot was made, and this, added to other charms, made her quite irresistible. She laughingly told us that Pepper-Pot was best on Sunday, for it was a heathen dish. Its origin was clothed in mystery.

It takes three or four days to cook Pepper Pot, but when it is done it is a worthy creation. Dark, rich, heterogeneous, with an unanalysable flavor, it possesses an apparently mild flavor until you have half finished your dishful. Then it begins to burn insidiously, first your tongue, then your palate, then your throat, until you feel gently aflame. It is not a wholly unpleasant sensation, and we all ate bravely.

Mr. Clemens remarked, when the silence of discovery had first fallen upon us, "This would be a very good dish if it had a little pepper in it." We all smiled humidly, and furtively wiped our eyes.

After luncheon some curious neighbors came in to call, and among them was one who did not win the affection of any of us, nor of Mr. Clemens, whom she particularly wished to impress. We had an opportunity then of seeing Mr. Clemens's tactics. He had a wonderful way of suddenly disappearing, of slipping into space, of melting into a misty background, when he wished to escape a person who bored him, that was the perfection of art. Sometimes, when circumstances prevented this disappearance of his physical self, he nevertheless absented himself mentally, so that the undesired one felt, all at once, that he was talking to the unanswering air. Withal Mr. Clemens always remained courteous and dignified, and never for an instant conveyed the thought of rudeness. Indeed, we never saw him angry or impatient except when he could not find a match-box in his pocket, or when his waitress failed to bring him his bacon grilled as he liked it. Even then he was simply whimsical in his wrath. The great disturbances usually found him calm and philosophical.

Mr. Clemens cared nothing for the excursions, that were sometimes proposed, to visit some object of interest. He used to say that he had probably seen the oldest house in the world, the longest street, the biggest city, the most wonderful cathedral, the highest mountain -- so why should he bother himself now, in his old age, to see second-rate curiosities? So he showed no interest in crystal caves, nor natural bridges, nor coral gardens, but he loved to sit on the veranda and drink in the changing beauty of sky and sea, or to take long drives under cedar arches or over palm shaded roads that ended suddenly in the surf.

He never played golf, that we knew of, but he was exceedingly fond of billiards. It was a pretty sight to see him teaching his little girl friends to play, and encouraging them by letting them beat him.

|

|

They assumed a high moral attitude.

|

In the evening we often used to play cards in his room. The only game we ever played was Hearts. Mr. Clemens usually prefaced the game by saying to Mr. Rogers, in a tone of kindly remonstrance: "Now, I sincerely hope you are not going to make any display of your disagreeable disposition tonight. Do try to show us some pleasant sides of your character."

Mr. Rogers, with a perfectly serious face, replied in the same vein, and this was kept up throughout the evening, so skillfully that the other two never grew weary. On the contrary, we were convulsed with silent mirth.

They, Mr. Clemens and Mr. Rogers, each had a theory that the other would be a hope less outcast were it not for his regenerating influence. They assumed a high moral and didactic manner when they reasoned with one another. Sometimes, however, there was a sweet gravity in their intercourse, and that was at such moments as when Mr. Clemens read McAndrews' prayer and Mr. Rogers listened, with a moisture in his eyes, to the beautiful pathos of his friend's voice.