Home | Quotations | Newspaper Articles | Special Features | Links | Search

MARK TWAIN and

|

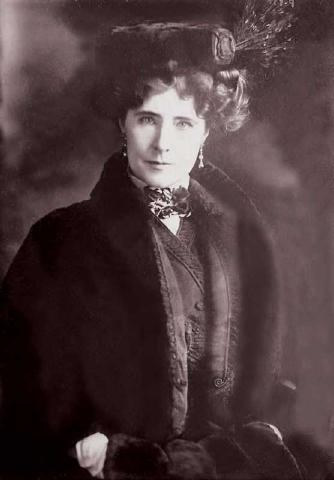

Elinor Glyn (1864-1943) |

Elinor Sutherland Glyn who began her literary career as a British fashion writer in 1898 achieved notoriety in 1907 with Three Weeks - a steamy romance novel which was shocking for its time. The novel was banned in Canada and condemned by religious leaders in the United States -- a sure sign of success in the sales arena. At the height of her fame Glyn was thought of as a "daring love analyst" and called herself "a high priestess of the God of love." By the time of her death in 1943, however, her work was considered "old fashioned" -- an indication of how much social attitudes had changed in thirty years.

In the winter of 1907 Glyn traveled to the United States and met Mark Twain. Biographer Michael Shelden writes that Twain and Glyn met at a dinner given by Daniel Frohman at Delmonico's restaurant in New York in December 1907. Shelden quotes from Isabel Lyon's recollection of the meeting where Lyon described Glyn as "a woman with milk-white skin, tawny red hair & green eyes; her gown a sea-green soft silk & she wore a strange oriental chain, as her only ornament" (Shelden, Mark Twain: Man in White, p. 189). Glyn hoped to gain a public endorsement from Twain for her novel Three Weeks and requested a private meeting with him in the near future.

Twain wrote about their meeting and her endeavors stating "She has come to us upon the stormwind of a vast and sudden notoriety." (The Autobiography of Mark Twain, edited by Charles Neider, 1966 edition, p. 353.) Twain read Three Weeks and offered his spin on the adulterous hero and heroine of the novel:

They recognize that they were highly and holily created for each other and that their passion is a sacred thing, that it is the master by divine right and that its commands must be obeyed. They get to obeying them at once and they keep on obeying them and obeying them, to the reader's intense delight and disapproval, and the process of obeying them is described, several times, almost exhaustively, but not quite - some little rag of it being left to the reader's imagination, just at the end of each infraction, the place where his imagination is to take up and do the finish being indicated by stars [****] (AMT, Neider, p. 354.)

Twain met with Glyn later that month and they visited for about ninety minutes discussing her novel and the laws of nature. Twain recalls:

Some days afterward I met her again for a moment and she gave me the startling information that she had written down every word I had said, just as I had said it, without any softening and purifying modifications, and that it was "just splendid, just wonderful," She said she had sent it to her husband in England. Privately I didn't think that that was a very good idea, and yet I believed it would interest him. She begged me to let her publish it and said it would do infinite good in the world, but I said it would damn me before my time and I didn't wish to be useful to the world on such expensive conditions. (AMT, Neider, p. 357).

The following pamphlet was privately printed in 1908 by Glyn and reported their conversation as follows:

Mark Twain on "Three Weeks"I must write of the interesting time I had with Mark Twain who sent to ask me to go and see him, as he had been ill and could not come out to see me. I went at half after three and stayed until five. I wish there had been a phonograph to take down what he said. I will try to report it accurately. He is a dear old man with a halo of white silky hair and a fresh face, and the eyes of a child which look out on life with that infinite air of wisdom one sees peeping sometimes from a young pure soul. To find such eyes in an aged face proves many things as to the hidden beauties in the character. Mark Twain was dressed in putty-coloured -- almost white -- broad-cloth, very soigne and attractive looking. We sat on a large divan, and he gave orders that we were not to be disturbed; and then, after a few more or less ordinary exchanges of sentences, he began about "Three Weeks," which was the subject he had asked me to come and discuss with him. He proceeded to hold forth, almost as if he were addressing an audience very slowly, choosing words, and slightly gesticulating with one hand, while he held a cigar with the other, which he smoked most of the time. He began -- "I have read the book, and I like it, manner and matter. It is a fine piece of writing; but I see why the public condemn it and call it immoral." (I said "Why?") Then his face became whimsical. "Because you have shown what is God's law against man's law, and in this crazy world, and from their most ancient religious books downwards, every volume that is written, every law that is made, is to trample under foot God's laws, and the laws of Nature. Every human creature -- as every animal -- obeys a law of instinct. We could almost class the animals by describing their instincts. The tiger is ferocious, the rabbit is timid -- each has its characteristics -- its law, which it obeys; given it in the beginning, we presume, by an all-wise Creator. We, who are descended from all the higher animals, have in us a conglomeration of these instincts -- these laws -- to obey. One man is more ferocious, so that at the least irritation he sees red and eventually wants to kill. Another firm is timid, and does not want to combat anything. Neither are in this frame of mind all the time. They have others from their conglomerated ancestry; but, all are obeying laws beyond themselves. And when God created beings with the force, and the passion, and the strength of 'Paul' and your 'Lady,' they were obeying a natural law in their instant coming together. God was to blame -- if any blame is to be attached to a noble reailization of his law -- in bringing them together. They were obeying laws, unknown to themselves; and no strength of will, and no convention, could have kept those two apart, because the law of God and Nature in them was to bring it to the highest point -- or, recreation -- the absolute law of Nature. There is, however, another law of Nature, equally strong, which is the love of parents for children. If the 'Lady' had had a child by her husband, the King, then two 'laws' would have been in conflict, because her mother-instinct would have been to protect that child, and not to injure it by scandal or disgrace. But she had no child; therefore, there was this immense unfettered force of the first great law of all things, to give herself to her mate. In this topsy-turvy, crazy, illogical world, Man has made laws for himself. He has fenced himself round with them, mainly with the idea of keeping communities together, and gain for the strongest. No woman was consulted in the making of laws. And nine-tenths of the people who are daily obeying -- or fighting against -- Nature's laws, have no real opinion. Opinion means deduction, after weighing the matter, and deep thought upon it. They simply echo feeling, because for generations forbears have laid something down as an axiom. They do not investigate or weigh for themselves. The axiom of the forbears was, 'It is immoral to follow God's law, unless bound by man's law and a wedding ring.' Therefore, at once, without a moment's thought of their own reasoning, the situation of 'Paul' and his 'Lady' is condemned -- and you have written an immoral book, because you saw more clearly, and wrote of God's law." (I said I wished someone had the courage to say this for me publicly

-- so he replied): (I said I was deeply touched, and asked him why he did not write all these views about the "laws" for the benefit of his countrymen.) He said he had written a book upon the subject, which would be published at his death, as there was no use in saying such things while alive, as his "law" was to protect his daughters, and a dead man's views were respected and often followed, but a live man's as often derided. "We live in a crazy world," he said. "You have shown it admirably by making 'Paul' and his 'Lady' pay a heavy price for the breaking of man's laws - but who knows? They may have completed one of God's laws and made it perfect in the doing." (I said I had been reproached for the detailed descriptions of their love passages, if, as I assert, the book has an elevated soul motive.) He said, "Fools! Fools! -- poor fools! -- every word of it is the evolution of the matter -- a masterly deduction of cause and effect, from the instinct of animal attraction on the tiger-skin, to the first hint of danger -- through the passion and the beauty of the scenery, to the highest of all, when, seeing the other woman's child in her arms, the 'Lady' wishes for the recreation of herself and her love. Every note of it is the result of cause, the logical effect of such cause. You are a very deep thinker -- you must have limit for eons of time." (I felt ashamed to say "Three Weeks" had taken me only about two months to write -- but I confessed at last.) Then Mark Twain said: "I dare say, but it had been simmering through years of thought. It took me nine years to evolve 'Joan of Arc' -- but a very short time to write it." ~~~~~ [Glyn's pamphlet also included the text of the letter of protest Twain sent to her after receiving a copy of the typescript of her interview.]

|

According to Glyn's grandson, Anthony Glyn who wrote Elinor Glyn: A Biography, (Doubleday & Co., 1955), Elinor and Twain were together at a dinner given by Daniel Frohman where "Mark Twain made a kind and most entertaining speech about Elinor. Also at the dinner was John Barrymore, who made a point of telling her how much he had himself enjoyed Three Weeks (Glyn, p. 155). As of this date, no speech Twain may have made about Elinor Glyn have been recovered.

In September 1908, the little pamphlet Mark Twain on Three Weeks again appeared on Twain's doorstep -- this time in the hands of a newspaper reporter requesting a comment. Twain's response was published in the following story:

Twain Says He Told Her "Book a Mistake."

|

For more information on Elinor Glyn, see the website for her

archives at Reading University Library.

Home |

Quotations | Newspaper Articles

| Special Features |

Links | Search