Home | Quotations

| Newspaper Articles

| Special Features |

Links | Search

SPECIAL FEATURE

Mark Twain's Writings on Fasting and Health

plus

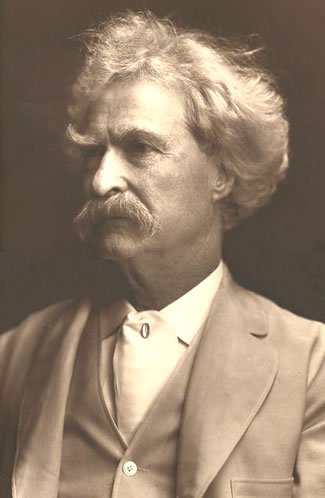

The Story Behind the A. F. Bradley Photos

A. F. Bradley photos provided by Dave Thomson.

|

In May 1919 writer George Wharton James published an article in Physical Culture magazine discussing Mark Twain's news report of the 1866 Hornet disaster first published in the Sacramento Daily Union. The article also appeared in the December 1866 issue of Harper's Magazine under the title "Forty-three Days in an Open Boat." In 1899, Twain again wrote of the incident in "My Debut as a Literary Person." James'

article illustrates how the Hornet incident impacted Twain's

later sketch titled "At the Appetite

Cure."

The Physical Culture article was unique in that it published

for the first time some photos of Twain taken by renown photographer

A. F. Bradley. James revealed how he was instrumental in convincing

Twain to pose for these photos as a fund raising effort to benefit survivors

of the San Francisco earthquake disaster. (It

was a cause to which Twain had already lent his support). The Bradley

photos survive today as some of the most popular of Twain ever taken

and continue to be favorite choices for a number book jackets and posters.

The following is the complete text of James' article including photos

that accompanied it. |

He began life as Samuel L. Clemens and ended it as Mark Twain. He was America's foremost humorist, philosopher and man of letters. |

Physical Culture

May 1919

MARK TWAIN - An Appreciation of His Pioneer Writings on Fasting and Health

by George Wharton James

ILLUSTRATED BY HITHERTO UNPUBLISHED COPYRIGHT PHOTOGRAPHS BY A. F. BRADLEY, NEW YORK

(Part I)

Everyone familiar with the life habits of Mark Twain knows how he reveled in smoking, contending that he was moderate in the use of cigars in that he never smoked more than one at a time, and that he was not averse to his "tot" of strong waters every day. It was his custom to make fun of all hygienic rules and precautions, and jokes galore are scattered throughout his books concerning the folly of self-denial of the appetite. Yet in his practice, his life, Mark Twain was far wiser than his jests seemed to indicate. For he was something more than a mere--though great--humorist. He was also a great philosopher. Nothing that he ever wrote more perfectly illustrated this than one of his earliest literary efforts. This early-day story made so deep and profound an impression upon my mind that I can recall its every detail, though it is fully thirty years since I read it. It is published in the collected (Harper & Brothers) edition of his works as "My Debut as a Literary Person." He tells of having written an article about the burning of the clipper ship Hornet on the line, May 3, 1866. Mark Twain was in Honolulu when the fifteen starved and ghostly survivors arrived there after spending forty-three days in an open boat with only ten days' rations of food.

Mark was sick in bed when these men arrived, but Anson Burlingame, who was on his way to China to negotiate the treaty that afterwards bore his name, happened to be there and had Mark taken down to the hospital on a stretcher to meet the shipwrecked men. As no one else of the newspaper correspondents seemed to see what a scoop the story was, Mark made a great hit with it, as well as justified himself in later putting in a special bill for it at a hundred dollars a column (three solid columns.)

The point I wish to make to my readers is this: Mark Twain then learned that, although that shipwrecked crew arrived in Honolulu mere skinny skeletons, "with clothes hung limp about them, fitting them no better than a flag fits the flagstaff in a calm," they soon recovered, and gathered strength rapidly, and within a fortnight were nearly as good as new and took ship to San Francisco. This clearly demonstrated that their long period of fasting had done them no harm. The Hornet left New York in January of 1866. It was a first-class ship, a fast sailer, and provisioned with an abundance of canned meats and fruits to help out the usual ship fare. Everything went well until May 3rd, when fire broke out and the captain decided to get away in the ship's boats. In the hurry of launching them two were injured. Four sick sailors were brought up on deck, one of them a "Portyghee" who had been "soldiering" throughout the whole four months' voyage, nursing an abscess.

The captain, with two passengers, and eleven men were in the long boat. The rations were half a biscuit for breakfast; one biscuit and some canned meat for dinner; half a biscuit for tea; a few swallows of water for each meal.

Where should they go? What port aim for? The nearest islands were about a thousand miles away. The first night it rained hard, and while all got thoroughly drenched they filled their water butt and were thankful. They were so crowded that none of them could stretch out and take a good sleep.

For five weeks they endured this, with all the other hardships--baking hot in the day time, occasionally wet through with rains, a heavy and dangerous sea at times, and seeing their tiny stock of provisions gradually growing less and less. While they still had a month's wandering of the seas ahead of them the captain recorded in his log (May 17) that they had only half a bushel of breadcrumbs left.

Now note! According to one of the diaries kept the men seemed pretty well and the feeblest of the sick ones formerly unable to stand his watch on board ship was wonderfully recovered. This was the "Portyghee" that "raised the family of abscesses."

They had the usual excitement and elevation of hope at seeing a sail on the horizon, and then the corresponding depression as the vessel disappeared. They caught a few boobies, birds that consist mainly of feathers and managed to exist on tiny rations doled out from the canned goods that still remained. Then the boats were compelled to separate, each going "on its own," and doing the best for itself. Its food became scarcer; despair made them silent, thus adding to other imaginable and unimaginable horrors, the muteness and brooding of desperation.

And here comes the passage of Mark's philosophy and practice that so forcefully struck me when I first read it many years ago.

"Considering the situation and circumstances, the record for the next day, May 29, is one which has a surprise in it for those dull people who think that nothing but medicines and doctors can cure the sick. A little starvation, can really do more for the average sick man than can the best medicines and the best doctors. I do not mean a restricted diet; I mean"--and the italics are Mark's own--"total abstention from food for one or two days. I speak from experience; starvation has been my cold and fever doctor for fifteen years, and has accomplished a cure in all instances. The third mate told me in Honolulu that the 'Portyghee' had lain in his hammock for months, raising his family of abcesses and feeding like a cannibal. We have seen that in spite of dreadful weather, deprivation of sleep, scorching, drenching, and all manner of miseries, thirteen days of starvation 'wonderfully recovered' him. There were four sailors down sick when the ship was burned. Twenty-five days of pitiless starvation have followed, and now we have this curious record: 'All the men are hearty and strong; even the ones that were down sick are well, except poor Peter.' When I wrote an article some months ago urging temporary abstention from food as a remedy for an inactive appetite and for disease, I was accused of jesting, but I was in earnest. 'We are all wonderfully well and strong, comparatively speaking!' On this day the starvation regimen drew its belt a couple of buckle holes tighter: the bread ration was reduced form the usual piece of cracker the size of a silver dollar to the half of that and one meal was abolished from the daily three. This will weaken the men physically, but if there are any diseases of an ordinary sort left in them they will disappear."

Note well this last sentence, and remember it was written by a humorist, one who was--at least at that time--not supposed to waste much of his time on serious thought. It was not the product of a physician's or nurse's experience, but the observation of a keen-brained layman. He saw that fasting would drive out ordinary disease. And that observation of his led me to my own studies of fasting, so that when, years and years later, the idea was openly advocated, I knew that of which I spoke when I heartily endorsed and fought for it, in spite of opposition from those whose medical and practical knowledge was, or should have been, far more extensive than mine.

To return now to the story of the shipwreck. On May 30 the captain had one can of oysters; three pounds of raisins; and one can of soup; one-third of a ham; three pints of biscuit crumbs. And there were fifteen starved men to live on it while they crawled what they thought was six hundred and fifty miles, but in reality was twenty-two hundred.

June 4 the captain reported the bread and raisins all gone and the day following they had nothing left but a little piece of ham and a gill of water, all around.

June 11 with all their food gone one of the passengers wrote in his diary that it was his firm trust and belief that they were going to be saved.

And so indeed they were. June 15 they sighted land. Two noble Kanakas swam out and took the boat ashore and two white men kindly received them. They were taken to the hospital. There Mark saw them, and as he says: "It is an amazing adventure. There is nothing of its sort in history that surpasses it in impossibilities made possible. In one extraordinary detail--the survival of every person in the boat--it probably stands alone in the history of adventures of its kind…

"Within ten days after the landing all the men but one were up and creeping about. Properly, they ought to have killed themselves with the "food" of the last few days--some of them, at any rate--men who had freighted their stomachs with strips of leather from old boots and with chips from the butter case; a freightage which they did not get rid of by digestion, by other means. The captain and the two passengers did not eat strips and chips, as the sailors did, but scraped the boot-leather and the wood, and made a pulp of the scrapings by moistening them with water. The third mate told me that their boots were old and full of holes: then added thoughtfully, 'but the holes digested the best!'"

I am glad to thus bring to the attention of the readers of PHYSICAL CULTURE this story and especially Mark Twain's deductions upon the fasting made so long ago. He persisted in the fasting habit throughout his life, and while no one will attempt to defend, from the hygienic standpoint--Mark's smoking and drinking habits, there can be little question that he prolonged his life by his occasional fasts.

That he was seriously interested in the subject is clearly evidenced from his "Appetite Cure," a roaring burlesque of the Bohemian method of treating those whose pampered appetites began to loath the luxuries they had fattened on.

In his "Appetite Cure" Mark Twain presents is ideas on fasting though in a most excruciatingly funny and exaggerated fashion that, to my mind, is one of the striking features of his humor. He tells of the place in Bohemia, a short day's journey from Vienna, where on goes to have his failing appetite treated. After a fooling introduction you are told that the Hochberghaus stands solitary on the top of a densely wooded mountain and that it is called the Appetite Anstallt. Professor Haimberger met Twain on his arrival and found out that though he had had all the most tempting things upon his table he could eat next to nothing.

The doctor handed him a menu and asked him to pick out from it what he would like to eat. Of course it was made up of impossibilities: "At the top stood touch, underdone, overdue tripe, garnished with garlic; half-way down the bill stood young cat; old cat; scrambled cat; at the bottom stood sailor-boots, softened with tallow--served raw. The wide intervals of the bill were packed with dishes calculated to insult a cannibal.

He remonstrated with the doctor for joking with him over so serious a matter. The doctor said he never was so serious in his life. The "appetite-cure" was his main dependence for his living. He had to cure people or lose his business. This led Mark to apologize for taking the food named on the menu from the mouths of the doctor's children. But the doctor denied that his children ate such trash. It was only his patients that he provided these things for.

But Mark was not hungry. He declined even the most tasty of the suggested items, though he was informed that the rule of the house was: "If you choose now, the order will be filled at once; but if you wait, you will have to await my pleasure. You cannot get a dish form that entire bill until I consent."

Mark refused again, and airily told the doctor to send the cook to bed as he was sure there was going to be no hurry, and then asked to be shown to his room.

Once there the doctor gave him full freedom to smoke and read all he liked and drink all the water he cold and warned him that as his case was very stubborn he had better refrain from eating any of the first fourteen dishes on the menu.

"Restrain myself, is it?" Mark cried: "Give yourself no uneasiness. You are going to save money by me. The idea of coaxing a sick man's appetite back with this buzzard-fare is clear insanity."

Without food he retired to bed and slept--my--how he slept! For fifteen hours he never awoke, but when he did it was with visions of Vienna coffee, bread, etc., etc. Yet when he rang the bell he was referred to the "Cure's" bill of fare. What, that loathsome stuff! He would none of it! After his bath he started for a walk, only to find, to his amazement, the door was locked. There was no leaving the room. At two o'clock he had been twenty-six hours without food and he was not only hungry, but "strong adjective" hungry. He read and smoked and read and drank water, and then to vary it, drank water, read and smoked. At first the thought of the infernalnesses of the Cure's menu nauseated him, but after forty-five hours of fasting he ordered the second item on the list--"A sort of dumpling containing a compost made of caviar and tar," but it was refused him. For the next fifteen hours he tried to get other items, but always met with a refusal, until as last he conquered all his prejudiced and half famished ordered item No. 15 "Soft-boiled spring chicken--in the egg; six dozen, hot and fragrant!"

In fifteen minutes the dinner was there, with the doctor, who congratulated the patient upon his recovery, but, when he asked Mark a question he impatiently waved him away: "Don't interrupt me, don't--I can't spare my mouth, I really can't."

Then the doctor stopped him. He could now be trusted with a beefsteak and potatoes. Vienna bread and coffee, which, of course, he ate with a relish, dripping "tears of gratitude into the gravy all the time--gratitude to the doctor for putting a little plain common sense into me when I had been empty of it so many, many years."

The second part of the story is devoted to a rehash of the shipwreck yarn I have already referred to, making Dr. Haimberger one of the party, and having him learn the great lesson of the benefit of fasting. He thus again enforces it, and the reasons for it, upon the minds of his readers and has Haimberger commend the system and explain that he got his idea of the "Appetite Cure" from that shipwreck experience. Here is his scheme: Don't eat till you are hungry. If the food fails to taste good, fails to satisfy you, rejoice you, comfort you, don't eat again until you are very hungry. Then it will rejoice you--and do you good, too."

He then asserts that all of the German and Austrian "cures" are "his" system disguised--covert starvation. Grape-cure, bath-cure, mud-cure--it is all the same. The grape and the bath and the mud make a show and do a trifle of the work--the real work is done by the surreptitious starvation." Then follows a statement of a day's treatment, hour by hour, "Six weeks of this regimen--think of it. It starves a man out and puts him in splendid condition. It would have the same effect in London, New York, Jericho--anywhere.

And he winds up his most serious and sane, wise and wholesome, needed and practical advice, wrapped up, however, under the most boisterous kind of fooling with the following truism as every Physical Culturist knows:

"Put yourself on a single meal a day, now--dinner--for a few days, till you secure a good, sound, regular, trustworthy appetite, then take to your one and a half permanently, and don't listen to the family any more. When you have any ordinary ailment, particularly of a feverish sort, eat nothing at all during twenty-four hours. That will cure it. It will cure the stubbornist cold in the head, too. No cold in the head can survive twenty-four hours' unmodified starvation."

And now it becomes my pleasure to tell how the accompanying photographs of Mark Twain--never before seen by the public--were obtained. (Go to Part II of this article.)