Quotations | Newspaper Articles | Special Features | Links | Search

including index and photos of Gerhardt's works

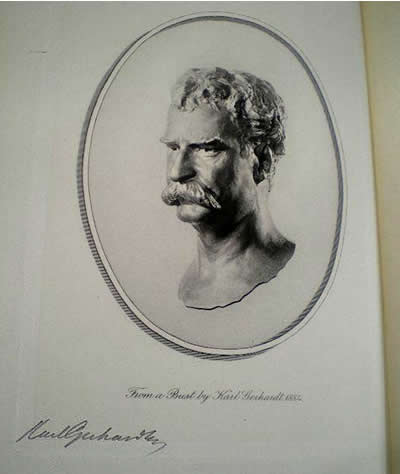

Bust of Mark Twain by Karl Gerhardt used as frontispiece for first edition of ADVENTURES OF HUCKLEBERRY FINN |

"You are those poor little people's god..."

"If ever there was a woman who believed in her husband's talent--it was Harriet Josephine Gerhardt. And if ever there was a husband who faded into obscurity after the death of a wife, it was Karl Gerhardt.

Born in Boston on January 7, 1853 and educated at Phillips school in that city, Karl Gerhardt was destined for fame as a sculptor of Ulysses S. Grant, Mark Twain, and a number of men famous in their time now forgotten. Little is known about Gerhardt's parents who were of German origin. The 1870 census for Chicopee, Massachusetts shows seventeen-year-old Gerhardt apprenticed to a house painter. He later spent a year and a half in the army. He began his business life as a machinist at the Ames Foundry in Chicopee, Massachusetts--a company that specialized in building Civil War cannons during the conflict between the Union and Confederacy. The company turned its attention to casting memorials to fallen soldiers after the war ended. In 1874 Gerhardt traveled to California but by 1880 he had returned east and married a girl ten years younger than himself.

Harriet Josephine, often called "Hattie" or "Josie" was born in Dalton, Massachusetts in 1863 to Austin E. Gloyd (1830-1865) and Amanda M. Sweet Gloyd (1835-1905). Hattie's father died when she was two years old leaving her mother a widow with four children. The story of Gerhardt's courtship with Hattie, who was later referred to as the adopted daughter of Charles McClellan, is unknown.

The Gerhardts were living in Hartford, Connecticut at the time the 1880 census was taken. By 1881 Gerhardt was employed as chief mechanic at the Pratt and Whitney Machine Tool Company, a company that was working to perfect the Paige typesetter, --an invention in which Mark Twain would later invest a fortune and lose it. Gerhardt's annual salary at Pratt and Whitney was about $350 (equivalent to about $6,000 in year 2000 dollars.)

In his free time, Gerhardt dabbled in art and sculpting statues of Hattie who served as his model. On February 21, 1881, Samuel Clemens wrote his colleague William Dean Howells telling of his first encounter with Hattie Gerhardt. According to Clemens, Mrs. Gerhardt appeared uninvited on his front door step at 10 AM one morning with a plea that Clemens admired for its earnestness and sincerity. She was determined that the famous "Mark Twain" who lived in a mansion in the prestigious Nook Farm community of Hartford accompany her home and admire a sculpture her husband Karl had just completed. Clemens further described how Hattie went to the home of his next door neighbor Charles Dudley Warner, editor of the local Hartford Courant newspaper with the same request.

Several days later Clemens and his coachman drove to the Gerhardt's home and, in the same letter to Howells, he described the couple's meager living quarters with paintings and sculptures scattered about the room. Clemens expressed amazement at a life size statue of Hattie, nude to the waist. Clemens wrote to Howells:

Well, sir, it was perfectly charming, this girl's innocence & purity--exhibiting her naked self, as it were, to a stranger & alone, & never once dreaming there was the slightest indelicacy about the matter. And there wasn't; but it will be many a long day before I run across another woman who can do the like & show no trace of self-consciousness.

| Clemens described twenty-six year old Karl as being as beautiful in spirit as his wife, "But she had to do the talking--mainly--there was too much thought behind his cavernous eyes for glib speech." |   Photo and

signature of Karl Gerhardt

Photo and

signature of Karl Gerhardtfrom the Kevin Mac Donnell collection. |

Based upon positive appraisals of Gerhardt's potential by noted experts James Wells Champney and John Quincy Adams Ward, Clemens and his wife Olivia agreed to personally finance Gerhardt's education. A sum of $3,000 was initially agreed upon for financing five years of training in at the prestigious Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris. On March 6, 1881, the New York Times commented under the heading of "Art Notes:"

Karl Gerhardt is another young sculptor who starts for Europe to obtain a thorough training in his art. He was lately a draughtsman in Hartford for a firm of manufacturers, and through the encouragement and assistance of Charles Dudley Warner, "Mark Twain," and the sculptors Ward and St. Gaudens has made his first move to fame or failure. (New York Times, March 6, 1881, p. 8.)

Shortly before the couple departed Hartford, Clemens gave them

a French language book and a copy of Anatomy for Artists

by John Marshall. Clemens inscribed the Marshall book:

The undersigned bought this book under the impression that it was a humourous work--&"got left." He asks Mr. Karl Gerhardt to take it off his hands & feels that he can recommend it as a mighty stupefying creation. ** |

The Gerhardts arrived in Paris on March 17, 1881, and Gerhardt immediately began instructions in art under Francois Jouffroy (1806-1882), St. Gauden's former teacher. Within a few months Gerhardt requested additional funding from Clemens to pay for live models--the study of which helped propel him to a higher ranking in his class.

The next several years Hattie and Karl exchanged dozens of letters with the Clemens family. Hattie's letters to the family were often filled with pleading for encouragement and support. In one letter dated May 24, 1881, Hattie wrote to Clemens:

I wonder & wish so very often if you do love us just a little bit--even aside from the talent and do you know I do not like to have you fond of anyone else but me and truly, I often get quite jealous thinking that perhaps you do a great deal.

Clemens' letters to the young couple were filled with encouragement

and advice to avoid social interactions and to concentrate on

studies. When Karl was worried about his future, Clemens wrote

on August 31, 1881:

Every time one wastes a thought on the future he misses a trick in the present. For instance, if I am out with a gun, & stop a moment to calculate the chances of next year's gunning, I shall surely lose the birds that fly over my head during that wasted moment.** |

For that portrait by Mrs. Joe seems a wonderful performance, more wonderful than her other specimens, which later I could begin to duplicate myself in five years, but not the portrait in thirty-five.** |

With the additional costs for art lessons for both Gerhardts

as well as higher than anticipated living costs, Clemens began

to express concern that the Gerhardt's would soon run out of funding

based upon their original $3,000 agreement. In a letter dated

September 30 and October 1, 1882, Clemens wrote about the budget

shortfall and how badly they had underestimated the funding needed

for five years of training:

But an ounce of result informs better than a pound of forecasting; a paragraph of actualities is worth more than a page of estimates.** |

When William Dean Howells planned a trip abroad in the summer of 1883, Clemens asked him to stop in Paris and check on the young couple. On July 10, 1883, Howells wrote very favorably of his visit with the Gerhardts:

There was a stove in the middle of the room, a lounge-bed for the nurse and baby at one side, and a curtained corner where I suppose the Gerhardts slept. It was as primitive and simple as all Chicopee, and virtuous poverty spoke from every appointment of the place.

Howells further related that Karl had exhibited a small medallion of Mark Twain in the Paris Salon that received favorable notice. Howells concluded his letter by stating

You are those poor little people's god--I don't know but they'd like me to write you with the large G.

Shortly after Howell's positive report, Clemens agreed to continue

funding the Gerhardt's stay in Paris, writing to them on August

1, 1883:

|

The following year, Gerhardt began contemplating his professional career and plans for repaying Clemens. Gerhardt wrote to Clemens on May 27, 1884, rebuffing any suggestion that he could go to work for sculptors Saint-Gaudens or John Quincy Adams Ward. Gerhardt wrote that he craved his own independent career and begged not to be forced to play "second fiddle" to anyone. While Hattie remained in Paris employed in teaching the English language, Karl returned to America in July 1884 with the goal of obtaining commissions.

|

The following month Gerhardt was working to complete a bust of Mark Twain that would later be used as a frontispiece for the first edition of Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. When the first bust was accidentally destroyed after four weeks of hard work Gerhardt went immediately to work and constructed a better likeness in a matter of days. |

A photo of the bust of Mark Twain by Karl Gerhardt was etched by artist William Harry Warren Bicknell and used as a frontispiece for the Adventures of Huckleberry Finn in the 1899 uniform edition of Mark Twain's works. Photo from the Kevin Mac Donnell collection. |

In the fall of 1884 Gerhardt began jockeying with competitors for the assignment of creating a statue of Nathan Hale for the state capitol building at Hartford. He requested Clemens' help in gaining the commission over the other leading candidate Hartford sculptor Enoch S. Woods. The pressure was on for Gerhardt to successfully land the Hale commission and on January 5, 1885, Hattie wrote Clemens from Paris:

...say you do not dislike us because we have not succeeded just as quickly as I though we would & that you will have patience just a little longer? Oh, how I long & pray that Karl will soon have a commission--if he doesn't I cannot imagine what will become of us.

In March 1885 the official choice was made. After much debate regarding whether or not Hale should have an equestrian statue, Gerhardt was awarded the commission. The following year--March 1886, Gerhardt begged Clemens to loan him $3,000 he needed in order to complete Nathan Hale. Gerhardt's statue of Nathan Hale was cast in bronze in December 1886. Gerhardt received $5,000 (approximately $92,000 in year 2000 dollars.) On December 21, 1886, Gerhardt wrote Clemens concerning the remarks about the statue he received from Connecticut Governor Henry Harrison:

Gov. Harrison remarked "You have behaved miserably but your statue is admirable."

If he knew how little I cared for myself in comparison with my images his breath might have been spared.

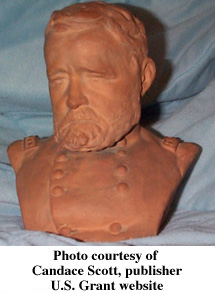

In March of 1885 Twain's own publishing house Webster and Company was engaged in publishing the memoirs of General U. S. Grant who was dying of throat cancer. On March 20, 1885, Twain and Gerhardt went to the General's home in New York and showed him a clay bust. According to an entry in Clemens' personal notebook, he and Gerhardt arrived at General Grant's about 2:30 in the afternoon and Clemens asked the family's opinion of the bust that Gerhardt had made from a photograph. The family expressed approval and interest in having the same artist who made Clemens' Huck Finn bust make one of Grant. General Grant was gracious and allowed Gerhardt to bring in his clay and work beside him while he rested. After the work was finished, Clemens noted that it was the best likeness of the General ever made and would be the last one made from life

Always susceptible to new business ventures, Clemens became involved in arrangements for mass producing and selling replicas. Gerhardt's busts of General Grant were sold by subscription--a method of selling that Twain had used for selling his books. Terra cotta busts were sold for $5.00 and bronze for $50.00. Promotional material for sales of the bust included a copy of the letter Fred Grant had written to Gerhardt praising the likeness. However, evidence indicates that the sale of Grant busts did not prove to be a financial success.

|

|

|

See additional photos and details of Grant's bust.

On April 1, 1885, Gerhardt expressed fear that sculptor James Alexander Wilson MacDonald would be given permission to cast General Grant's death mask at some future date with the intention of selling it. Clemens was asked to use his influence with the Grant family to obtain permission for Gerhardt rather than MacDonald to cast a death mask. It was a request Clemens could not bring himself to ask the family and he shuffled Karl to intermediary, General Adam Badeau, Grant's military secretary and the request was granted by the General's son Fred Grant.

Entries in Clemens personal notebook indicate he may have been losing patience with Gerhardt regarding the financial assistance he continued to provide him. A notebook entry dated April 14, 1885, written in German:

The principal feature of Gerhardt's character is thanklessness. Don't forget this statement.

On April 27, 1885, the New York World reported that the Grant family had engaged Munich sculptor Rupert Schmid to complete a bust of the General. Clemens was no doubt angered to read that Schmid had disparaged Gerhardt's work: "The face has a somewhat worn look, but I shall remove that, and I feel confident that I will, after one more sitting, be able to present a faithful likeness of Gen. Grant as he appeared before he was prostrated by the cancer." Clemens also realized that the sale of competing busts would not bode favorably for his personal business interest in the project. In spite of Schmid's claims, Gerhardt continued to receive approval of his work from the Grant family.

By May, 1885 Hattie had returned from Paris in poor health and Clemens continued to provide financial assistance to the Gerhardt's throughout 1885. One notebook entry contained various dollar amounts loaned to the couple, including a "water cure" treatment for Hattie, prefaced with:

I have given Gerhardt several thousand dollars worth of my time & a good deal of trouble besides. I ought not to charge for that, neither ought he to fail to remember it.

In spite of whatever private grievance Clemens may have held against Gerhardt, he continued to suggest money-making projects involving memorials for General Grant. A June 4, 1885, letter from Clemens declared, "You must have the first Grant statue." Clemens urged Gerhardt to have it ready for presentation to the city of New York within a few months. Clemens undoubtedly realized the time of Grant's death was fast approaching and pledged $500 to the project.

In anticipation of being on hand when General Grant's death

came, Gerhardt traveled from his home in Mt. Vernon, New York

to Mt. McGregor near Saratoga where Grant was spending his final

days. Writing Clemens letters from the Hotel Balmoral at Mt. McGregor,

Gerhardt provided a first hand account of the Grant family's affairs

during the final month of Grant's life. Ingratiating himself with

the Grant family while working on a bust of Grant's granddaughter

Nellie, Gerhardt received permission from Grant's son Jesse to

produce a final sculpture of the General. Clemens expressed great

delight regarding the new Grant piece in a letter dated June 26,

1885:

There is limitless inspiration in the thought that the features which you are modeling are those of a man whose name will still be familiar in the mouths of men in a future so remote that the very constellations in the skies of to-day will have visibly changed their places.** |

However, in a letter dated June 28, 1885, Clemens expressed

agitation that Gerhardt had ordered photos taken without inquiring

about prices first:

In fact, a man who orders anything without first fixing the price is an ass--simply an ass. I have tried it often enough to know. You are young & can reform; don't ever be that kind of ass again.** |

On June 26 Gerhardt reported to Clemens, "I shook hands with the Genl yesterday and he remembered me." Additional letters from Gerhardt informed Clemens that his discussions with General Grant's sons were ranging from business propositions for a Constantinople railroad to statues for General Grant.

On June 28 Clemens departed Elmira, New York for the long fourteen hour trip to Mt. McGregor for his last visit to the dying General. In his personal notebook Clemens described their last discussions related to an article in the Century magazine as well as investments in the Constantinople railroad project. In a letter to his wife dated July 1, 1885, Clemens wrote, "The photograph of the General which Gerhardt got taken is a most impressive & pathetic picture. Gerhardt's bust of Jesse Grant's little child is a very successful thing, & they are all pleased with it."

Clemens returned to Elmira in time for Fourth of July fireworks while Gerhardt

remained at Mt. McGregor. Clemens wrote Gerhardt regarding his thoughts about

prices for a future Grant monument or statue on July 6:

My idea is $25,000. If you were a sculptor of established reputation, I should say $40,000--but you ain't. I named the $25,000 mainly because the name of so great a man as General Grant ought not be connected with a low priced statue.** |

On July 14 Gerhardt, without giving details, wrote Hattie that there had been some unpleasantness between himself and the Grant family. It is probable that newspapers were reporting that Gerhardt was standing by to make the General's death mask and the news was disconcerting to Mrs. Julia Grant. Hattie, in turn, forwarded Gerhardt's letter on to Clemens asking him for assistance and she and her daughter departed for Mt. McGregor to smooth the situation.

Clemens, in turn, fired off a letter to Gerhardt dated July

18 to depart Mt. McGregor immediately:

The General sick all these months, the family distressed, worried--a stranger present whose projects are of a sort to get into print & add to the worry--don't you see, it is a most easy thing for you to become a burden & one too many. So if I were you I would pack up & go back to Mount Vernon; & I would not gloze over my reasons, but would squarely & candidly state my reasons for doing so--to Col. Fred or Mrs. Jesse, for instance. You don't want to become a bother to the family & you mustn't. Don't tarry--go right along.** |

By July 19 Hattie and her baby had arrived at Mt. McGregor and Gerhardt's favor with the Grant family had been restored. Gerhardt wrote Clemens that the Grants did not wish him to leave until his current work on the General's study was complete. He also wrote that Hattie "will be the means of my getting a commission here." Hattie wrote Clemens describing the warm friends she had made with the Grant family. She informed Clemens she had played her first game of billiards and described how Jesse Grant had posed for Gerhardt in the General's dressing gown while Col. Fred Grant "criticised."

There is no evidence to indicate that Gerhardt ever had another personal visit with the dying General other than the occasion of shaking his hand on June 26, 1885. On July 23, 1885, former President Ulysses Grant succumbed to his cancer. Two days later on July 25, Gerhardt wrote Clemens regarding the death mask:

Dr. Douglas saw the mask as did the Mexican minister (Leon Romero) and both pronounced it an unusually fine one.

Imagine the trembling Gerhardt taking is first death mask, and from such a personage--It is only nice to think that no one else did it the family did not wish it.

The sketch I have not touched since the 23rd the day he died. I had draped it all before that and everybody's enthusiastic over it. I am casting it now.

On the 26th Gerhardt reported to Clemens that extra guards had been placed around Grant's cottage because Rupert Schmid had arrived and had "threatened he would have a mask at any cost." And on the 27th Gerhardt wrote, "Some roses that Josie and I sent to the Grant family are the only flowers that have been placed on the coffin through loads of flowers have been sent them. How sweet a compliment it is."

After Grant's death Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper featured a cover article with Gerhardt at work on the mask. The Springfield Republican newspaper, dated July 26, noted that Gerhardt had spent time at Mt. McGregor and made a model of the General representing him in his chair in his beaver cloth dressing gown, holding his pencil in his right hand and his writing pad on his knee. (The current location of this final Gerhardt study of General Grant remains unknown.) That fall, Gerhardt's name appeared at the end of an article in September 1885 issue of The North American Review trying to rouse national interest in construction of a Grant memorial. For Gerhardt, it was a memorial that never came to be.

No written contract existed between Gerhardt and Grant's family concerning the death mask. Some news reports indicated that Gerhardt had, in fact, made a duplicate of the mask and later historical evidence would bear this out. On October 25, 1885 the New York Times offered scathing comments on Gerhardt's refusal to hand the death mask over to the Grant family. In a column under the heading "Art Notes," p. 6:

The death mask which was allowed to be taken from Gen. Grant with such undue haste by the young sculptor, Karl Gerhardt, is held by him as his private property. Was this the intention of the family? "I have the death mask in a vault in New-York," the sculptor is reported in the Chicago News to have said. "It is my private property, but I have no intention of disposing of it. In fact, $10,000 has been offered for it and refused. It is proposed to make it historical and to have it handed down from generation to generation, as the death mask of Washington has been." By what right is it Mr. Gerhardt's property? And if it is, what guarantee is there that it will not be sold? Suppose he should die. The whole thing looks suspiciously like an arrangement to sell something to the Government at a high price later on which the sculptor ought not to have the power to sell. Because this young, unskilled workman happened to apply to the family first, the delicate operation of taking a death mask was intrusted to him. Nobody knows whether he did it well or ill. In either case, the mask belongs to the Grant family, not to Mr. Gerhardt. (New York Times, October 25, 1885, p. 6.)

December 1885 found Gerhardt and the Grant family in bitter dispute over ownership of the death mask with Gerhardt writing Clemens, "I should like to continue a friend of the family of course but shall keep the mask 'whether or no.' " Clemens was asked to intervene in the matter that threatened to develop into a lawsuit and Clemens, fearing a scandal in the newspapers, agreed to step in. Clemens knew that Gerhardt would "kick, and kick hard" but the proposal put forth from Clemens was to erase all personal debts from Gerhardt to himself--a sum of approximately $17,000 by Clemens' calculations (over $300,000 in year 2000 dollars)--if Gerhardt would hand over the mask.

No letter of record exists of Gerhardt's reaction to Clemens' offer; however, on December 21, 1885, Gerhardt sent a one sentence letter to Charles Webster stating, "Please deliver to Col. Grant or Mrs. Grant the death mask of Genl Grant placed in your hands by me."

The Grant death mask fiasco did not prove an insurmountable barrier to further relations between Gerhardt and Clemens. The two continued to socialize and discuss business matters related to Gerhardt's career. Gerhardt attended dinners in the Clemens home and a family birthday party for Clemens' daughter Susy in March 1886. Gerhardt's relationship with some members of the Grant family did not seem to suffer irreparable harm. On September 20, 1886, Gerhardt wrote Clemens that Mrs. Jesse Grant and her father were supporting him for a commission for the Lick Monument to be built in San Francisco. New Orleans writer Grace King wrote in her memoirs of meeting Gerhardt at the Clemens home in the summer of 1887. And in the fall of 1887, Karl Gerhardt tried to interest Clemens in establishing a commission for a monument to Henry Clay Work, a noted Hartford native.

Evidence is lacking as to whether or not Clemens knew Gerhardt had made a duplicate of copy of Grant's death mask. However on January 6, 1896, the New York Times reported the following under the headline "Death Mask of Gen. Grant Completed":

HARTFORD, Conn., Jan. 5. - The death mask and shield of Gen. Grant, designed by the artist, Walter Sanford, and the sculptor, Karl Gerhardt, have been completed here in the studio of Mr. Sanford, and the original will be presented to one of the New York Grand Army posts. The design is taken from the mask of Gen. Grant which was made by Mr. Gerhardt twenty minutes after the death of the soldier, at Mount McGregor, in 1885. The design is decorated with oak and laurel leaves, and is mounted on a panel. It is surrounded with the simple inscription, "U. S. Grant, 1822 - 1885," in burned letters. The effect is decidedly picturesque. (New York Times, January 6, 1896, p. 1.)

By 1889 Gerhardt had achieved enough success allowing him to invest in sixty

acres of land near the Hartford capitol that he proposed to develop under the

name of Cottage Grove Improvement Company. Gerhardt offered Clemens a deed to

five acres of land free of charge if Clemens would build a factory for the Paige

typesetter. On October 7, 1889, Clemens replied that he wanted to proceed

cautiously and stated:

I seem to live in a kaleidoscope the materials are the same yet every morning when I get up they have formed themselves into a wholly new figure overnight.** |

Throughout the latter half of the 1880s Gerhardt had received commissions for memorial statues in Connecticut, New Jersey, New York, Massachusetts, Vermont, and at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. Competition among designers and architects for the job of creating Civil War memorials was fierce. And in one case, Gerhardt himself may have crossed the professional line and taken credit for a design created by noted Hartford architect George Keller for the Soldiers' monument in Utica, New York. Whatever the arrangement between Keller and Gerhardt, Keller later wrote to his wife on July 13, 1889, regarding the competition for the San Francisco Lick Monument:

The San Francisco people after deliberating for nearly two years have finally rejected all the designs so that goose is cooked and I am rather glad of it for little Gerhardt is a very disagreeable creature to have business dealings with.

Karl and Hattie's son Lawrence was born in 1890--at a time when Gerhardt's flow of commissions was slowing. By mid 1891 Clemens' financial situation, due to poor business investments related to the Paige typesetting machine, had forced him to close his Hartford mansion and take his family to live abroad. The small number of letters to Clemens and his attorney Franklin Whitmore that survive after 1890 indicate Gerhardt was himself in financial difficulties attempting to cash in a life insurance policy on himself that Clemens held as well as recover his investment in the Paige typesetter.

In 1891 Gerhardt who was living at Cottage Grove in Bloomfield, Connecticut was included in the volume Illustrated Popular Biography of Connecticut. The book was compiled and published by J. A. Spalding of Hartford, Connecticut. The reference book included short biogaphies of the most prominent citizens in the state, many of whom had been interviewed for the profiles. According to Gerhardt's entry:

The home of Mr. Gerhardt in Bloomfield is a delightful one. Besides the wife who was the inspiration of his first attempts in sculpture, there are two children, daily adding joy and delight to his domestic surroundings. He is connected with the Congregational church and is independent in politics (p. 140).

The delightful picture of domestic bliss painted in the biographical entry foreshadowed the decline of the man and his career.

On December 21, 1891 Gerhardt wrote to Andrew J. Coe of Meriden, Connecticut requesting additional funds for a death mask he had made of Coe's mother, Harriet Rice Coe who had died a few months earlier on October 26.

|

Bloomfield, CT, Dec 21, 1891 Dear Sir: Shall I send the mask of the late Mrs. Coe to you by express: I agreed if a duplicate was made in plaster to not charge for it; but under the circumstances; I must; My charges are $25.00 Mr. Karl Gerhardt |

In December 1891 Gerhardt responded to a want ad in the Hartford Courant placed by noted Hartford inventor Francis H. Richards:

|

Bloomfield, Connecticut, December 28, 1891 Dear Sir: Seeing your ad in the morning's Courant and as at the present time I am temporarily disengaged I answer. Learned the machinist trade with Ames Mfg. Co. Chicopee Mass. Worked for one year at Browne and Sharpe's Providence R.I. studied drafting and mathematics at Institute of Technology, Boston. Worked as draftsman with the Ames Co. and also as draftsman for Pratt and Whitney Co., seven years in all. Will work for $3.00 three dollars a day. Yrs truly: Karl Gerhardt "Draftsman" |

Surviving correspondence in the Connecticut State Library indicates Gerhardt did work occasionally for inventor Francis H. Richards during the years 1895-1897. On several occasions Hattie Gerhardt also wrote to Richards requesting favors of work or recommendations for her husband.

In 1895 Gerhardt's letterheads indicated he was in partnership with artist and architect Walter Sanford. A few months after the New York Times reported in January 1896 on the Sanford and Gerhardt death mask project of Grant, the paper reported Sanford and Gerhardt were threatening to sue the state of New Hampshire over a Franklin Pierce statue. In a news story headlined "Artists to Sue a Statue Commission" the New York Times reprinted an article from the Hartford Post:

Walter Sanford, architect, and Karl Gerhardt, sculptor, both of this city, have notified all the members of the Franklin Pierce Statue Commission of the State of New Hampshire that they intend to hold each individually responsible for the expense of $1,200 which they incurred on the representations of the Chairman of the commission that their design for the statue of ex-President Pierce had been accepted.

The commission was appointed by the Legislature of the State of New-Hampshire to arrange for the erection of a statue on the Capitol grounds at Concord of President Pierce, who was a native of the State. The Chairman of the commission is Col. J. W. Robinson, and Gov. Busiel is a member. The commission advertised for sketches to be submitted by artists, and last Fall it was announced that the design submitted by Walter Sanford and Karl Gerhardt of this city had been accepted.

Messrs. Sanford and Gerhardt received frequent assurances from Col. Robinson that their design was satisfactory. He came to Hartford and inspected the model and gave directions for the artists to go ahead with their work. An opposition to Sanford and Gerhardt developed, and on March 26 of this year the commission rejected all sketeches and again invited competition from other artists. Messrs. Sanford and Gerhardt wrote to the commission asking for an explanation, and did not receive a satisfactory reply. (New York Times, May 11, 1896, p. 2.)

In 1897 Gerhardt's letterheads indicate he was employed in Hartford at the Pope Manufacturing Company, a company known for building some of the first bicycles in America. Francis Richards assisted Gerhardt in filing a patent on an automatic wrench and on June 3, 1897, Gerhardt was awarded his wrench patent. It was the same day Hattie Gerhardt died. Gerhardt would later write that Hattie was the victim of a "rusty nail."

Harriet Josephine Gerhardt died in Bloomfield, Connecticut and her death certificate and cemetery records indicate that she was buried in section five of Spring Grove Cemetery in Hartford. There is currently no marker or headstone that indicates Hattie Gerhardt's final resting place. According to the cemetery caretaker, the exact plot of Hattie's grave is now lost and could be one of about forty graves that remain unidentified. Gerhardt, the sculptor who had created so many notable memorials for the country's famous, left no evidence of a marker for his wife's gravesite.

| In 1899 American Publishing Company issued a multi-volume uniform edition of Mark Twain's works. The 1899 Autograph Edition features signatures of various artists who contributed their work. Adventures of Huckleberry Finn featured a photo of the bust of Mark Twain that had been etched by engraver William Harry Warren Bicknell. Karl Gerhardt signed the page. The edition was limited to only 512 sets in the United States. |  Frontispiece of the 1899 Autograph Edition of Adventures of Huckleberry Finn features Gerhardt's autograph |

The 1900 U.S. census for Connecticut shows Karl Gerhardt living on Amity Street in Hartford with his daughter Olivia and son Lawrence. Also living with him was a housekeeper Alena Stone (married name Stebbins) and her four-year old daughter Lillian Viola Stebbins. Alena was a native of Hartford, Connecticut. On April 27, 1901 a notice appeared in the Hartford Courant newspaper indicating Karl Gerhard was petitioning the probate court to be allowed to sell property valued at about $250 that belonged to his minor children. In May 1901 Karl's eighteen-year old daughter Olivia Gerhardt, who shared her father's talent for modelling, married Hartford painter William Grant Beckwith. In 1902 Karl's first grandson William Karl Beckwith was born. Olivia Gerhardt Beckwith, namesake of Olivia Clemens, died May 7, 1906, of typhoid fever and was buried in Indian River Cemetery in Clinton, Connecticut. The exact date of Gerhardt's departure from Connecticut has not been firmly established. It is believed Gerhardt was living in New Orleans at the time of Olivia's death and according to sources now close to Gerhardt's descendants, attempts to notify him of her death were fruitless. Gerhardt's four year old grandson was abandoned by both his father William Beckwith and his grandfather Karl Gerhardt.

The 1908 edition of Soard's New Orleans City Directory listed Karl Gerhardt residing at 1229 Burgundy street. His occupation was listed as "bartender." On January 14, 1909, the New Orleans Times Democrat reported that the sculptor of U. S. Grant's death mask was living in obscurity within the city and engaged "in earning his living by hard work whenever it is obtainable." The report indicated that Gerhardt had employed attorney Pierre A. LeLong, Jr. to recover the original death mask of Grant from the estate of Walter Sanford of Hartford, Connecticut. Attorney LeLong was successful and the mask was shipped to New Orleans where LeLong had shown it to newspaper reporters. The arrangement Gerhardt had with Walter Sanford involving a duplicate of General Ulysses Grant's death mask remains a mystery.

On March 19, 1909, the Times Democrat reported plans by Gerhardt to exhibit his personal copy of General Ulysses Grant's death mask. According to the article Gerhardt "has been a resident of this city for some time, but owing to his dislike for notoriety, has never made himself prominent until sought out by those interested in showing to the public the mask."

Several months later Gerhardt mailed his last known letter to his benefactor Samuel Clemens. Clemens himself had lost a daughter and his wife Olivia several years earlier. Gerhardt's letter dated May 5, 1909, reads:

|

NEW ORLEANS, LA. 5.5.09-- Dear Mr Clemens-- So many years have elapsed since I saw you last in Hartford, that I suppose when you receive this, it will come in the nature of a surprise! Recently I made an Equestrian sketch of Gen'l Beauregard, and exhibited it; some notice being taken of it, as you will see by the enclosed "clipping" from T.D.) I met several people of prominence and made two busts which also attracted some attention copies of letters from my scrap book one of yours among the number were published together with an elderly person I enclose "clipping" [Clipping from New Orleans Times Democrat with Gerhardt's photo.] I believe I am making a bust of an old friend of yours one of your "Mississippi chums" the late Mr. John T. Moore; I am glad to be able to tell you of my return to my beloved art and think I have gained by the long enforced rest-- Lawrence now 19 years old shows remarkable talent and is modelling with me I suppose you heard of Josie's death poor girl--the picture of health and in two short weeks gone--the victim of a rusty nail-- Perhaps I can reach toward you, and grasp your hand, and tell you how sorry I feel for you in your bereavement--Well I'm living the simple life; but this return to modelling brings back sweet and bitter memories and I want you to know that my heart is very tender toward you and yours always Sincerely Karl Gerhardt-- |

No surviving letter of reply from Clemens has been found.

The April 23, 1910 census for New Orleans shows Karl Gerhard and his son Lawrence living on Hagan Avenue and his former housekeeper Alena Stone, who had divorced her husband Joseph Stebbins in 1901, is listed as the wife of Karl Gerhardt. Alena's daughter Lillian Stebbins is identified as Lillian Gerhardt. According to various New Orleans city directories, Gerhardt's occupation in New Orleans varied and included job titles of decorator, sculptor, draftsman, engineer, tailor, and bartender. The 1920 census documented Karl Gerhardt and his son Lawrence living in Chicago, Illinois with his occupation listed as a sculptor and Lawrence's occupation listed as a tailor of suits. Karl lists himself as widowed and Alena is shown in the 1920 census living with her married daughter Lillian Gerhardt Estain in Jefferson, Louisiana. The timing and reason behind Karl and Lawrence's relocation to Chicago has not been found. Sometime during the 1920s Gerhardt and his son Lawrence moved back to Shreveport, Louisiana. In 1922, the Shreveport city directory shows Gerhardt working as a driver for an ice company and Alena is once again listed residing with him. During the 1920s, Gerhardt--then in his 70s--along with Lawrence worked as tailors for their company they named Alawaka Tailoring. Alena Gerhardt disappears from the Shreveport city directory records in 1925. No marriage records for Karl Gerhardt to Alena Stone (her maiden name) have been found. No death records for Alena Stone Stebbins Gerhardt have been found. News reports detailing her association with Gerhardt have not been found.

In October 1929 Gerhardt applied for his U.S. Civil War Pension. Records show

he had served as a musician in the band for the U. S. Calvary during the Indian

Wars in 1875-1876 in Solano, California. Gerhardt's last years were spent in

a little studio next to Lawrence's home on Blanchard Road near Shreveport, Louisiana.

Gerhardt joined the local Shreveport Art Club, exhibited his works with them

and on one occasion gave a lecture regarding the making of Mark Twain's bust.

He gave occasional art lessons to special students he thought had potential

and also held a small job for the post office toting mail bags from the train

station to the post office. One month before he died, Karl Gerhardt listed his

occupation in the 1940 census as "landscape" artist. Gerhardt died

May 7, 1940. His obituary appeared on the front

page of the Shreveport Times. Gerhardt was buried in Blanchard Cemetery. His son Lawrence died in 1954 and

is buried nearby.

|

OTHER KARL GERHARDT ITEMS AVAILABLE:

Karl Gerhardt on the front cover of August 1, 1885 Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper

Karl Gerhardt's obituary in the Shreveport Times, May 8, 1940.

Karl Gerhardt's headstone in Blanchard, Louisiana

Acknowledgments for assistance and information provided:

Passages from Mark Twain's previously published letters and personal notebooks are from:

Quotations | Newspaper

Articles | Special Features |

Links | Search