Appreciation and Introduction

|

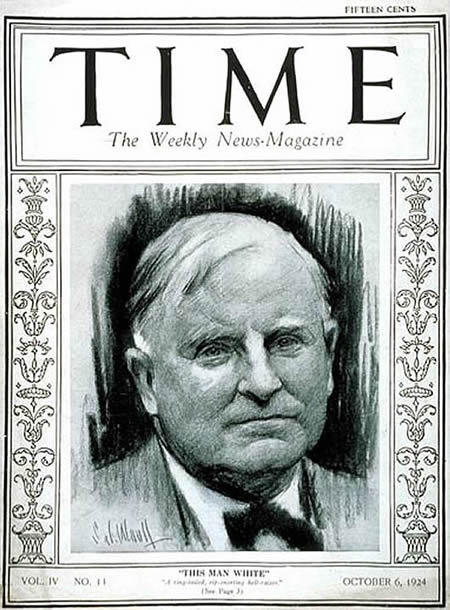

The Appreciation for the Gabriel Wells Definitive Edition of Adventures of Huckleberry Finn was written by William Allen White. White was born in Emporia, Kansas in 1868. He attended both the College of Emporia and the University of Kansas and at the same time worked in local newspaper offices both as a typesetter and a reporter. In 1895 he purchased the Emporia Gazette, a small-town, country newspaper which he published until 1943. White's common-sense and often crusading editorials brought him national attention. Eventually becoming known as the voice of middle America, White's contributions appeared in magazines such as Scribner's, McClure's, Atlantic Monthly and Harper's Weekly. He also published a succession of novels. |

William Allen White on cover of Time magazine, 1924 |

Sam Clemens owned at least two of White's books -- The Court of Boysville (1904) and an autographed copy of White's In Our Town (1906), a series of sketches about small town country newspapers. On June 24, 1906 Clemens wrote to White regarding In Our Town:

Pages 212 and 216 are qualified to fetch any house of any country, caste or color, endowed with those riches which are denied to no nation on the planet -- humor and feeling.

Talk again -- the country is listening (Paine, pp. 797-98).

In his Autobiography, White described his letter from Clemens, "a beautiful letter which, in my vanity, I framed and kept on my workroom wall" (White, p. 381).

White, however, became disillusioned with Clemens after meeting him in the fall of 1907. In his Autobiography, White writes:

John Phillips, one of the editors of McClure's, and Auguste F. Jaccaci invited Mark Twain to a luncheon and took me along, one autumn day in 1907. ...

The luncheon was at the Aldine Club on lower Fifth Avenue, an organization of publishers, writers, and master printers. And Mark Twain came in white flannel and a white hat. He wore a contrasting plain black bow tie. His hair was a fluffy halo of white around his head, and a heavy, drooping white mustache slightly colored by nicotine arched above a firm strong mouth. During the meal sprightly talk went around the board. The table was set in a little private dining room fifteen by fifteen, near a window looking down on the avenue. After we had finished, Mark Twain lighted a cigar rather formally, with what seemed to me theatrical ceremony, puffed it a few times and then rose from his chair and began to talk. Of course I was a young man and did not quite comprehend what was going on. Our guest was putting on a performance for us. He paced on the vacant area of the room in tracing rectangles, and diagonals across the rectangles, for two solid hours, and recited contemporary magazine articles which he had written and which heroized himself pretty strongly as a man who could not be imposed upon. He stuck closely to the text of his articles, which I had read and which I afterwards reread. It was an amazing thing to do -- to give a two-hour humorous lecture about himself to three comparatively unimportant people. We had other appointments that afternoon. Phillips tried to stop Mark Twain, but he roared ahead like an engine on a track. His hands were behind him as he walked, slightly stooped, and he droned on -- sometimes laughing at his own humor and sometimes indicating by facial grimaces a place for us to laugh. It was a conscious performance and greatly shocked me, though Phillips and Jaccaci had heard of our hero staging such acts before. But while we appreciated the distinction he was conferring upon us, we certainly were eager to get back to our afternoon's work. He did not realize that he had bored us. We parted pleasantly and I am sure he felt that he had greatly honored us and entertained us.

Men who knew Mark Twain -- particularly Mr. Howells, whom I afterwards told of the incident -- said that the oratorical habit was growing on him and declared that in his earlier days his sense of humor would have saved him from making such a spectacle. I am sorry, but that is the only memory I have of the greatest figure in American letters which the last quarter of last century produced. I had read his books in adoration. I still believe he is a monumental figure in American life as a philosopher, as a story-teller, as a representative and expounder of the teal American democracy. But my ideal, Mark Twain, was a little battered as we parted there at the doorstep of the Aldine Club and walked out into Fifth Avenue together in the late autumn afternoon (White, pp. 381-82).

In politics, White became a leader in the Progressive movement and helped establish the Kansas Republican League in 1912. In 1923, he received the Pulitzer Prize for the best newspaper editorial of 1922 titled "To An Anxious Friend" which championed freedom of speech. White continued to be an editorial writer for the Emporia Gazette until his death in 1944. In 1947 he was awarded a posthumous Pulitzer Prize for his Autobiography which his family published after his death.

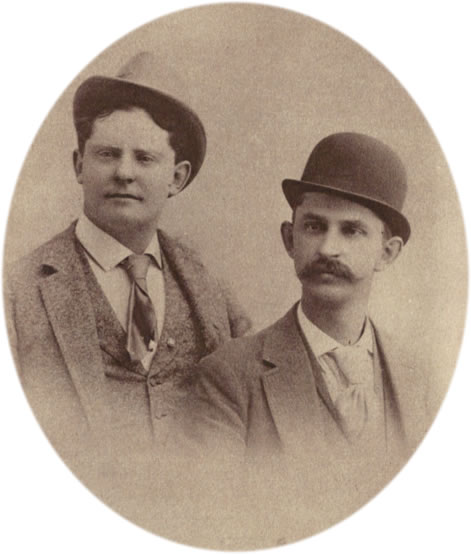

William Allen White and Albert Bigelow Paine, 1890s. |

White's contribution to the Gabriel Wells Definitive Edition of Adventures of Huckleberry Finn pairs his work with that of Albert Bigelow Paine. The two had co-authored Rhymes of Two Friends in 1893 but a business dispute over the book's distribution ended their friendship. |

White's Appreciation is perhaps one of the most unusual commentaries ever

written about Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. White fails to address

the issue of slavery that is heart and soul of Mark Twain's story. White's

Appreciation may have been distorted due to his former feud with Albert Bigelow

Paine who played a pivotal role in the production of the Gabriel Wells Definitive

Edition. Another possibility is that his disappointment experienced during

his meeting with Mark Twain in 1907 shaped his opinion of the work. A third

possibility is that White had not read the book since his childhood and failed

to grasp the full impact of the story through the eyes of an adult reader.

For whatever reason, White's Appreciation for Adventures of Huckleberry

Finn remains one of the oddest commentaries ever written regarding Mark

Twain's masterpiece.

|

AN APPRECIATION CONSIDER the middle of the nineteenth century in America. It was the time and the place of the great real-estate boom that populated the towns and the farms of the country from the Alleghany Mountains to the Pacific Ocean. Before 1880 the Civil War of the 'sixties had stopped the normal circulation of the American commercial blood. In the 'sixties we were almost paralyzed. In the 'seventies we began to awake. The farms were laid out, the towns were plotted, and a scant population was lured into what twenty years before had been known as the Great American Desert. But it was only the outline of the American civilization: vague, impressionistic, ugly enough, and it required a key or a glossary or a dream book to make it intelligible. Manufacturing was done chiefly in New England and a few Lake cities. A pious, prosperous aristocracy lived in towered, turreted, and tumultuous houses, furnished and trimmed in quarter-sawed oak, supplying the ideals for a restless population living in smaller houses or in apartments crawly with jig-sawed woodwork and painted to imitate quarter-sawed oak. The covered wagon of the 'sixties and 'seventies, with its drab contents, had almost ceased to dot the prairies. At the beginning of the 'eighties railroads conveyed the settlers in the emigration from the East to the West. For in those mad 'eighties the railroads were nearly finished on the American continent. When, lo! came the boomer. He was vivid. He painted a drab world with rainbow tints, laid out additions to the towns, and then the towns became cities; sold stock in visionary enterprises which actually became industries, and stimulated commerce where there had been only a swapping of chips and whetstones. And even the commerce came and stayed. No dream was too grotesque for reality. The boomer could not fashion a phantasmagoria too lively to defeat a crystallization in fact. So grew that miracle of commercial and industrial efflorescence that became the America of the last quarter of the nineteenth century. Partly

to do obeisance to it, partly to mock it, and somewhat as its subconscious

literary expression, repressed and rising upon another plane, came

Huckleberry Finn. Huck and the King and the Duke and the drab

Mississippi capered through a book. It was the epoch's gorgeous dramatization

of the story of the boom and the boomer. The raft with its motley

crew pictured in fantastic shapes the dull civilization of the day,

vitalized by the great hegira of Americans across the continent in

gaudy Pullman cars and noisy railroads to the vast madhouse in which

delusions daily were verified by realization. Huckleberry Finn

is Mark Twain's yip of delight at the things he saw all about him.

Those were days of horse play. The very gods of American destiny were

trying their rawest practical jokes upon the land and finding their

jokes taken seriously. Statesmen of Brobdingnagian stupidity were

sent into politics by the gleeful fates rolling and howling in the

grass of Elysium at the sumptuous asininity of their joke. And the

people accepted the gift of the gods in solemn gratitude! Financiers

who mortgaged the people's future and offered to them the mortgages

were sent around by incredulous genii. And what did the people do

but buy the mortgages! So Mark Twain, hearing the thunderous mirth

upon Olympus, caught the roll and cackle of it, and so made Huck and

his merry men. It was a masterpiece of fableizing. Huckleberry

Finn is more than a satire. It is symbolic history written not

with mere peals, but with crashes and crackling claps of joyous laughter

-- laughter at an age.

|

An Introduction by Albert Bigelow Paine follows the Appreciation.

|

INTRODUCTION WHEN Mark Twain, in 1875, had completed his first boy's story, The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, he wrote in a letter to William Dean Howells:

Clemens usually had several manuscripts in hand at once, and a year later, at Quarry Farm, Elmira, in his summer study, he put aside other things to let Huckleberry Finn relate his own adventures. Mark Twain had always loved the character of Huck, both in fiction and reality, and it was no trouble to allow him to tell his tale in his own way. Huck Finn, in life, had been Tom Blankenship, and in the story of Tom Sawyer he appears very much as he had appeared in reality during Samuel Clemens's childhood. There were several of the Blankenships, and the character of Huck in the second story is in a sense a composite of Tom Blankenship with his elder brother, Ben, at least so far as concerns one of the chief episodes in the story. Ben Blankenship was considerably older, as well as more disreputable, than his brother Tom. He was inclined to torment the boys by tying knots in their clothing when they went in swimming, or by throwing mud at them when they wanted to come out, and they had no deep love for him. But somewhere in Ben Blankenship there was a fine, generous strain of humanity that would one day supply Mark Twain with that immortal episode -- the sheltering of Nigger Jim. A slave ran off from Monroe County, Missouri, and got across the river into Illinois. Ben used to fish and hunt over there in the swamps, and one day found him. It was considered a most worthy act in those days to return a runaway slave. In fact, it was a crime not to do so. Besides, there was for this one a reward of fifty dollars, a fortune to ragged, outcast Ben Blankenship. The money and the honor he could acquire must have been tempting to the waif, but it did not outweigh his human sympathy. Instead of giving him up and claiming the reward, Ben kept the runaway over there in the marshes all summer. The negro spent his time fishing, and Ben carried him scraps of other food. Then by and by something of the truth was suspected. Some woodchoppers went on a hunt for the fugitive, and chased him to what was called Bird Slough. There, trying to cross a drift, he was drowned. Of course, such an incident made a deep impression on young Sam Clemens and his companions; and at a later period the author, Mark Twain, would not fail to recognize its literary and dramatic value. In fact, it presently became the chief motive, the great central idea, of the story. That the runaway Huck should fall in with runaway Nigger Jim was a thing which would happen naturally enough in Mark Twain's imagination, and nothing could appeal to him more than to personally conduct the the irresponsible, care-free journeyings of two such fugitives. It seems curious now that he could ever have abandoned the writing of such a tale until the last chapter and line had been finished. But here is a remarkable thing: he thought very little of the story indeed. Perhaps because the labor of it was so easy; perhaps the life to him so familiar and commonplace that he could not see the marvelous fascination it would have for the general reader. However, that may be, in one of his letters of the time he wrote it:

Clemens did give the story up when it was about half completed, seemingly without much regret, and did not touch it again for four years. He added some chapters to it t hen, working on it alternately with The Prince and the Pauper, which held his chief interest. Huck was presently put aside, and was not taken up again until after Mark Twain had made his return trip to the river for the purpose of finishing Life on the Mississippi, and had completed and published that volume. In the Mississippi book Clemens had used a discarded chapter from the story of Huck, and, reading over the latter manuscript, he found his interest in it sharp and fresh, his inspiration renewed. The trip down the river had revived it. He set to work on the story again, and finished it at a dead heat. This was in August, 1883. The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn was the first book which Mark Twain published himself. He was at this time associated with his nephew by marriage, Charles L. Webster, in one or more business enterprises, where agents were employed. Furthermore, Webster had assisted in the distribution of the Mississippi book. It seemed to Clemens a good time to try subscription publishing on his own account, and in 1884 he gave Webster the Huck Finn manuscript as a publishing experiment. Webster, a young man of energy and executive ability, distinguished himself in the new field. Clemens was not without good ideas. He discovered Kemble, the illustrator, among other things, and sold some advance chapters of the story, with Kemble's pictures, to the Century Magazine. These attracted wide attention, and by the time the book appeared Webster had a great heap of orders waiting for it. It was published in December, '84, and within a few weeks fifty thousand copies had been delivered. No former book of Mark Twain's had sold so largely in that brief time. The story of Huck Finn will probably stand as the best of Mark Twain's purely fictional writings. Sequels are dangerous things when the story is continuous, but the story of Huck is something more than a sequel to Tom Sawyer. The tale is altogether a new one, wholly different in environment, atmosphere, purpose, manner, everything. The account of Huck and Nigger Jim drifting down the mighty river on a raft, cross-secting the various primitive aspects of human existence, constitutes one of the most impressive, delightful examples of picaresque fiction in any language. It has been ranked greater than Gil Blas, greater even than Don Quixote; certainly it is more convincing, more human than either of these tales. In one of Robert Louis Stevenson's letters he wrote,

And Andrew Lang, writing for the Illustrated London News, in 1890, said:

Lang closed by ranking it as the great American novel, which had perhaps "escaped the eyes of those who watched to see this new planet swim into their ken." But Huck has not always and everywhere found approval. His story has been frowned upon by certain meticulous librarians, even evicted from their shelves. This is because of Huck's morals -- because he was not over-careful in the matter of statement, among other things, not always a proper example for youth. Huck's supreme virtue is his loyalty -- loyalty to Nigger Jim, loyalty to his disreputable brute of a father, loyalty even to those two river tramps and frauds, the king and the duke, for whom he lied prodigiously, pitying them in their misfortune. The king and the duke, by the way, are not elsewhere matched in fiction. The duke was patterned after a journeyman printer Clemens had known in Virginia City, but the king was created out of refuse from the whole human family -- "all tears and flapdoodle," the very ultimate of disrepute and hypocrisy -- so perfect a specimen that one must admire, almost love him. ''Hain't we got all the fools in town on our side? and ain't they a big enough majority in any town?" he asks in a critical moment -- a remark which ranks him as a philosopher of classic distinction. We, too, are full of pity at last, when this pair of rapscallions ride out of the history on a rail, and we feel some of Huck's loyalty, and all the truth of his comment, "Human beings can be awful cruel to one another." "The poor old king," Huck calls him, and confesses how he felt ornery, and humble, and to blame, somehow, for the old scamp's misfortune. "A person's conscience ain't got no sense," he says, and Huck is never more real to us and more lovable than in that moment. Huck is what he is, being made so, and he cannot well be otherwise. He is a boy throughout -- such a boy as Mark Twain had known and in some degree had been. His story will preserve the picture of that kind of a boy, his period and his environment, for generations of other boys who will not be made worse by his example. ALBERT BIGELOW PAINE. |

Illustration List for Volume 13

The Gabriel Wells Definitive Edition of Adventures of Huckleberry Finn features the same frontispiece and the four illustrations by Edward Windsor Kemble that had appeared in the 1899 uniform editions of Adventures of Huckleberry published by American Publishing Company.

_____

References

Gribben, Alan. Mark Twain's Library: A Reconstruction. (G. K. Hall, 1980).

Paine, Albert Bigelow, ed. Mark Twain's Letters, Volume 2. (Harper and Brothers, 1917).

White, William Allen. The Autobiography of William Allen White. (Macmillan Company, 1946).

"William Allen White." Online at wikipedia, accessed 6 June 2010.

"Wm. Allen White, 75, Kansas Editor, Dies," The New York Times, 30 January 1944, p. 38.