Early History

The years after World War II saw a growing emphasis on the role of American literature in schools and colleges, slowly replacing the role long held by British literature. In 1948 the Modern Language Association (MLA) tried and failed to raise funds to publish definitive works of major American authors. However, publishing scholarly editions of American authors was a concept that slowly gained acceptance. By the 1960s questions of how to define and produce a scholarly edition of an American author's work were being debated and the guidelines established.

In November 1961 Harper and Brothers announced a merger with Row, Peterson and Company to form Harper and Row, Publishers, Incorporated. At the 1961 convention of the Modern Language Association in Chicago, Edwin Barber, an executive of the newly formed company proposed the publication of a new uniform edition of Mark Twain's works. Harper and Brothers had not issued a complete set in over thirty years. (Barber's proposal for such an edition came about five years before John Stevenson decided to forge ahead and fill that void by revamping the old Gabriel Wells and Stormfield editions into the Greystone Definitive Edition.) Present at Barber's brainstorming session were John C. Gerber, head of the English Department at the University of Iowa, Walter Blair of the University of Chicago, and William M. Gibson of the University of Wisconsin. Barber envisioned a scholarly edition that would be prepared and edited by leading Mark Twain authorities. He forewarned the men that not all of the Harper executives were convinced publishing a new scholarly edition of Mark Twain's works would be a profitable venture. Paul Baender of the University of Iowa and bibliographer William B. Todd joined the endeavor and the five men formed themselves into an editorial board to oversee the Harper and Row project. With a network of Mark Twain scholars across the country writing letters of endorsement to Harper executives, Barber received his company's permission in April 1962 to proceed with the Mark Twain edition.

In 1962 grants were being offered by the U. S. Office of Education to publish authoritative editions of works by writers such as Nathaniel Hawthorne, Herman Melville and others. However, at the time Barber proposed the Mark Twain edition, no guidelines had yet been established as to exactly what constituted an authoritative text or how one should be established. In May 1963 Gerber and his editorial board met in Chicago and decided upon the candidates to edit specific volumes of Mark Twain's works. Selections for editors were made based on previous areas of Mark Twain research without regard to previous experience in critical textual analysis -- how to weed out the errors that had occurred over the years as an author's work was re-typeset with each subsequent publication. Harper agreed to pay each volume editor $500 for research and a total of $8,750 for administration and general editing. Harper's total cash commitment to an edition proposed to run between 22 - 25 volumes was only $19,250.

The Original Editors

Academic professionals

who agreed to edit a new edition of the works of Mark Twain for Harper and

Row. The photo was made in 1964. The editors, their affiliation at the time,

and their proposed volumes:

Front row: left to right:

Hennig Cohen (b. 1919 - d. 1996), University of Pennsylvania - a volume

of short travel pieces

Warner Jenkins Barnes (b. 1934), University of Texas, bibliographer

who would help establish the Iowa Center for Textual Studies

Walter Blair (b. 1900 - d. 1992), University of Chicago, Adventures

of Huckleberry Finn

Gladys Carmen Bellamy (b. 1901 - d. 1973), Southwestern State College,

Oklahoma, Following the Equator

Roger B. Salomon (b. 1928 - d. 2020), Yale, The Prince and the Pauper

Middle Row:

Edwin Ford Barber of Harper & Row who proposed the new edition

William B. Todd, (b. 1919 - d. 2011), University of Texas, bibliographer

Arlin Turner (b. 1909 - d. 1980), Duke University, Pudd'nhead Wilson

William Merriam Gibson (b. 1912 - d. 1987), University of Wisconsin,

The Mysterious Stranger fragments

Franklin R. Rogers (b. 1921 - d. 2011), University of California -

Davis, Roughing It

Allan C. Bates, Forest Park, Life on the Mississippi

Back Row:

Howard G. Baetzhold, (b. 1923 - d. 2012) Butler, a volume of short

fiction from the middle and later periods

Hamlin L. Hill, (b. 1931 - d. 2002), New Mexico, The Gilded Age

James D. Williams (b. 1929), Fairleigh-Dickinson, A Connecticut

Yankee in King Arthur's Court

Louis J. Budd (b. 1921 - d. 2010), Duke, a volume of short political

writings

John C. Gerber (b. 1908 - d. 2003), University of Iowa, a volume of

the Tom Sawyer books

Paul Baender, (b. 1926 - d. 2006), University of Iowa, What Is Man?

and Other Philosophical Writings

Edgar Marquess Branch (b. 1913 - d. 2006), Miami University of Oxford,

Ohio, a volume of short early fiction

Albert E. Stone, Jr., (b. 1924 - d. 2012) Emory, Joan of Arc

Frederick Anderson (b. 1926 - d. 1979), University of California, Berkeley,

The Autobiography

Not pictured:

Roger Asselineau (b. 1915 - d. 2002), The Sorbonne, A Tramp Abroad

Leon T. Dickinson (b. 1912 - d. 2004), University of Missouri, The

Innocents Abroad

Paul Fatout (b. 1897 - d. 1982), Purdue, Speeches

Lewis Gaston Leary (b. 1906 - d. 1990), Columbia, a volume

of short critical works

Years of Struggle and Controversy

In 1963, a name for Harper and Row's proposed authoritative edition of Mark Twain's works still had not been decided nor had the format for the volumes. The year 1963 was also the year the Modern Language Association (MLA), an organization that included nine university presses and approximately 26,000 literary scholars from across the nation, formed the Center for Editions of American Authors (CEAA) whose purpose was to establish principles and procedures for producing authoritative texts of American authors. The MLA was concerned the existing editions of American authors were neither complete nor accurate. The organization felt that the future studies of American literature was at risk because access to original manuscripts was frequently restricted and rare editions published during an author's lifetime were extremely difficult to locate. The 1899 uniform editions of Mark Twain's works had been on library shelves over half a century and were deteriorating. Many first editions were in even poorer condition when they could be found.

Over the next several years, the CEAA developed recommendations that authoritative texts must be produced based on principles formulated by bibliographer Fredson Bowers. Under this concept, a textual analysis should begin with the earliest document available of an author's work -- usually the original manuscript. A textual editor should change it only to incorporate changes the author made, not changes made by a typist, previous editor, or typesetter. The textual editor should document changes made in each subsequent printing during the author's lifetime and provide the reader with reasons for rejecting certain changes or implementing any changes in the text. By the time a finished authoritative text was established, a reader or future scholar would have little need to work with rare manuscripts because the volume would contain a textual roadmap for all revisions from manuscript through subsequent printings. As William Gibson described it:

The work of collating the copy-text against all the other relevant forms is primary, inescapable, and even for the well trained and strongly motivated, soul-crushingly dull (William Gibson, Professional Standards and American Editions, p. 2).

(A comprehensive description of how Mark Twain's texts are established is online at "Textual Editing at the Mark Twain Project.")

The CEAA would not publish their editorial guidelines until 1967 in "Statement of Editorial Principles, A Working Manual for Editing Nineteenth Century American Texts." However, John Gerber and his editorial board were quickly becoming aware that the necessary research and labor required to get a scholarly edition ready for print would likely require $400,000 -- an amount that could not be met by Harper and Row. In 1964 Gerber obtained a grant from the United States Office of Education that eventually totaled about $182,000 to aid in completion of a twenty-two volume scholarly edition of Mark Twain's works estimated to take a period of four years to complete. The Center for Textual Studies at the University of Iowa was established as headquarters for the endeavor and the library there purchased a Hinman collator, a machine adept at detecting textual differences in impressions made from the same set of printing plates. The Hinman collator could detect plate wear and/or deliberate alterations in the plates used to print any given edition.

William Todd, a member of the Iowa editorial board, presented a paper at the annual meeting of the Modern Language Association in December 1964 detailing the problems the editors were facing. Todd explained that for Twain's major works alone, there were perhaps 400 different texts. According to Todd there were likely forty editions of The Innocents Abroad issued in Mark Twain's lifetime. Twain's entire output might be partially estimated by the 2,650 variant issues listed on cards filed with the Library of Congress. Todd called the Mark Twain situation unparalleled in editorial history. To produce an authoritative text of Mark Twain's works, editors would need to gain access to original manuscripts, magazine printings, first editions, the 1899 editions issued by American Publishing Company and the later printings of Harper's Author's National Editions -- some of which were issued in limited numbers. Todd recommended examination of both the Gabriel Wells Definitive Edition and the Stormfield Editions but called them textually inferior to anything previously published. Academic professionals who had signed on with the Iowa project believing their work would consist of writing an introduction and limited annotations were faced with the harsh reality of being in a situation for which they had no previous training. They were in over their heads.

Parallel Projects

While the Iowa project to publish a scholarly edition of Mark Twain's previously published works was struggling, across the country at the University of California at Berkeley, editors, scholars and graduate students were working on preparing for publication editions of Mark Twain's works that had either remained unpublished or published in such inadequately prepared editions as to be unacceptable to contemporary scholars. When Mark Twain's daughter Clara Clemens died in 1962, her father's papers were given to the University of California at Berkeley and they included a wealth of letters and manuscripts never before seen in print as well as a number of previously published manuscripts. Established in 1962, the California endeavor to publish this wealth of material was known as the Mark Twain Papers. Berkeley was also home to the University of California Press that was well equipped to handle such publishing projects. In 1964 Frederick Anderson of Berkeley was named as literary editor of the Mark Twain Papers. Anderson had also signed on to edit Mark Twain's Autobiography for the Iowa project. A few other editors including Walter Blair, William Gibson, Hamlin Hill and Franklin Rogers were also involved in both the Iowa project to publish previously published works and the California Mark Twain Papers project to publish material never before made public. It was inevitable that confusion would result from the existence of two similar projects devoted to Mark Twain. The Winter 1964 edition of American Quarterly featured an article titled "Twain in Progress: Two Projects" by Paul Baender of Iowa and Frederick Anderson of Berkeley. The article tried to set the record straight for the academic community and spelled out the responsibilities of the two separate projects.

National Endowment for the Humanities and Competition for Funding

Since 1963 the MLA had been seeking grants to help publish authoritative editions of major American authors -- often in competition with other individuals. Among these competitors was powerful literary critic and author Edmund Wilson (b. 1895 - d. 1972) whose vision for uniform editions of American authors was based on a French model known as the Pleiade editions, a famous series of reprints of the French classics. On September 29, 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed into law the National Foundation on the Arts and Humanities Act. The act created the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) -- the culmination of a movement for the United States to invest in their own national culture. Both Edmund Wilson and the MLA submitted proposals requesting funding assistance from the NEH to publish works of American authors. The NEH decided to grant the MLA $300,000 in funds that were to be redistributed to projects the MLA felt met the strict criteria for publishing authoritative and scholarly editions. Edmund Wilson's proposal for a "Constellation" series would be granted $50,000 if his group could establish an appropriate process for administering such a grant. They did not.

Projects that applied for and received annual grants from the CEAA were expected to follow its guidelines for authoritative critical texts, and to publish promptly; they were denied funding for taking too long to publish, and for being unwilling or unable to follow those guidelines. Grants were given on an annual basis and designed to enforce adherence to the guidelines. An examiner would inspect each book, and only those meeting the requirements would receive a seal denoting "An Approved Text."

A textual editor was required to follow CEAA guidelines about what to choose as the basis of the text and reveal to the reader what changes had been made and why. The basic idea is to begin with the earliest document available, usually the manuscript, and change it only to incorporate changes the author made, not those made by the typist, editor or typesetter. The CEAA seal was printed on the copyright pages of volumes that met the criteria.

Funds from the National Endowment for the Humanities were distributed beginning in August 1966. The Mark Twain Papers at Berkeley received NEH funding to continue with their editorial work on establishing texts for Mark Twain's works that had never before been published.

Across the country in Iowa, in the late summer of 1966, John Gerber's project was struggling. That endeavor's biggest supporter, Edwin Barber, left Harper and Row. His replacement, Marion S. Wyeth, Jr. felt the project was becoming less and less a viable money maker. No longer interested in bidding on such a project, in February 1967 Harper and Row washed their hands of the endeavor. It had been six years since Barber first proposed the edition and the Iowa volume editors had not submitted a single complete manuscript. In effect, the Iowa editorial board was a group of university teachers and bibliographers without one viable manuscript or a publisher in sight. In early 1967 Gerber attempted to obtain additional funding from the NEH for the Mark Twain works project but was told the guidelines he had been following for establishing texts were too lax.

The criticism that Gerber's guidelines were too lax was based on his editors' practice of choosing the first editions of Mark Twain's books as copy-text -- not the original manuscript and subsequent printings. In addition, changes the editors were making with the copy-text were not being strictly recorded. In some instances the editors were modernizing the text. Inadvertent and deliberate modernization were among the things the CEAA objected to in the Iowa practices. From the beginning of the Iowa project, editors had decided against using illustrations from the first editions of Mark Twain's works. That decision was also risky because throughout a number of books, Mark Twain had continually referred to the illustrations. To edit out such text required editorial intervention that was risky and led to controversy.

Progress in California

In early 1967 the University of California Press issued three volumes of Mark Twain's previously unpublished works: Mark Twain's Satires and Burlesques edited by Franklin Rogers; Letters to His Publishers, 1867-1894 edited by Hamlin Hill; and Which Was the Dream? and Other Symbolic Writings of the Later Years edited by John S. Tuckey. The three volumes were edited with almost no federal support and feature no acknowledgments regarding grant funding. Although the existence and application of strict editorial standards was still in its infancy, two out of three of the volumes did receive the CEAA seal of approval. Only Franklin Rogers's Mark Twain's Satires and Burlesques was published without the CEAA seal. According to John Gerber, the volume was too far along in the production process to have been afforded that opportunity. Which Was the Dream? and Other Symbolic Writings of the Later Years contains the CEAA seal but contains no textual notes indicating how the text was established. Errors in the text were later ridiculed by literary critic Edmund Wilson. Hamlin Hill's Letters to His Publishers, 1867-1894 also lacks textual notes indicating how the texts were established and in some instances the letters were silently edited by Hill. These early volumes in the Mark Twain Papers series indicate that the standards for CEAA approval had yet to reach maturity.

John Gerber's best option for ever getting a uniform edition of Mark Twain's works into print lay with the University of California Press. In August 1968 the University of Iowa and the University of California Press hammered out an agreement to publish what would be known as the Iowa-California edition of Works of Mark Twain. Gerber and his editors would be required to comply with CEAA standards. By December 1972 Gerber's original editors would no longer be in charge of textual work. Their roles were limited to writing introductions and explanatory notes. The job of establishing authoritative texts of Mark Twain's works in compliance with CEAA standards fell largely to the graduate students at the Berkeley Mark Twain Papers office and Bernard Stein of the Berkeley staff was given the responsibility of overseeing the textual policy of the Iowa-California volumes. The editors who had originally signed on to edit the editions found themselves deferring to decisions made by graduate students. Roger Salomon who had been assigned to edit The Prince and The Pauper resigned in protest. Other editors who were part of the original project left as time wore on.

Caught Up in Edmund Wilson's Crosshairs

By 1968 journalist and author Edmund Wilson was being called the new "Dean of American letters." Wilson, a graduate of Princeton University, began his career with the New York Sun. He later wrote for Vanity Fair, The New Republic, The New Yorker, and by the 1960s he was contributing to The New York Review of Books, a bi-monthly magazine geared to the literary elite. When he died in 1972, his obituary in The New York Times described him:

Celebrated primarily as a critic, Edmund Wilson was accounted by common consent the most erudite of them, the most omniscient, the most productive, the most finicky and the most dyspeptic. There was, inevitably, some question as to whether he was the most sagacious or the most perceptive but there was no doubt, as the years passed, that he was the most didactic and probably the most influential ("Edmund Wilson Dies," The New York Times, 13 June 1972).

Described as a "literary quarreler," Wilson was disdainful of those he considered lesser intellects and he sported a reputation for impatience and bad manners. In 1963 he was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation's highest civilian honor for his literary work. President John Kennedy is reported to have defended Wilson's nomination saying, "This is not an award for good conduct but for literary merit" (Costa, Edmund Wilson: Our Neighbor from Talcottville, p. 41). The Medal of Freedom citation proclaimed Wilson as a critic and historian who had converted criticism into a creative act with a stern and uncompromising standard of independent judgment. When the MLA received funding to produce authoritative works of American authors and Wilson's own plan was tabled, he took aim at the MLA through the pages of The New York Review of Books in a two part series titled "The Fruits of the MLA" that was published September 26 and October 10, 1968. Described by Louis Menand as a classic example of Wilson's "late life peevishness," Wilson's intent was to "vaporize a harmless and well-intentioned cottage industry, the publication of scholarly editions" (Menand, The New Yorker, 8 August 2005).

Wilson struck at the MLA, the Iowa project and the Berkeley Mark Twain Papers project. Regarding the MLA, he wrote that the organization's periodical (PMLA) contained for the most part "unreadable articles on literary problems and discoveries of very minute or no interest." Wilson claimed to have a letter from a staff member of the Iowa Center for Textual Studies which intimated that the Mark Twain works project was "a boondoggle" that wasted government funds by hiring students to read Tom Sawyer backward word by word hunting insignificant typographic errors. Wilson confused the Iowa project with the Mark Twain Papers project, tainting the Berkeley project by association. Of the Mark Twain Papers project he wrote, "for the ordinary reader, who is not obliged to use them for a PhD thesis, these papers have no interest whatever ... there can be very little point in salvaging any he [Mark Twain] rejected." Wilson skewered the University of California's plan to publish Mark Twain's letters in piecemeal fashion suggesting it was only a plan to provide more jobs for the editors. Regarding the boasts of the MLA regarding its standards of editing and proofreading, Wilson pointed out three obvious, to him, errors in the 1967 edition of Which Was the Dream? edited by John S. Tuckey. Topping off Wilson's tirade was a condemnation of the contracts that academic scholars signed with the MLA which provided them with no royalties.

Written in 1968, the only portion of Wilson's tirade that still rings the loudest almost 50 years later is: "In the meantime we shall have to wait a century or longer before, according to the requirements imposed by the MLA, such texts will become available..." (Wilson, p. 9). Although he would not live to see it, the NEH provided startup money in 1979 for Library of America editions that were based on Edmund Wilson's vision of publishing lightly annotated classics of American authors, including the works of Mark Twain. The NEH continues to fund Library of America to keep individual volumes perpetually in print.

The Outcome

Members of the MLA sent letters of reply to Edmund Wilson trying to set the record straight regarding their endeavors. In 1969 the responses were gathered and published in a booklet titled Professional Standards and American Editions: A Response to Edmund Wilson. From 1966 to 1975 the MLA through its CEAA organization served as a "regranting agency" for NEH funding. In 1976 this role was eliminated as the NEH assumed primary control of the funding process. In September 1975 the CEAA was reorganized as the Committee for Scholarly Editions (CSE) with a focus on a wider range of scholarly writings. After 1975, volumes meeting the strict criteria for establishing texts received a CSE seal of approval that is similar in design to the old CEAA seal.

From 1972 to 1979 Frederick Anderson at Berkeley applied for NEH grants every two years for two separate grants -- one to edit the previously unpublished Mark Twain Papers and one to edit the authoritative edition of Works of Mark Twain -- the previously published works. In 1980 John Gerber turned over all his responsibilities for the Iowa-California edition to the Mark Twain Papers project at Berkeley and the Iowa Center for Textual Studies was discontinued. In 1980 Robert Hirst became general editor of the Mark Twain Papers and at the urging of the NEH, both the Works and Papers project were merged and received only one biennial grant under one editorial board. The combined endeavor was named the Mark Twain Project.

In 1997 when John Gerber published his memories of his work on the project, he referred to the Iowa-California edition as akin to a farce and gothic horror story. For Gerber it had been an endeavor filled with professional frustrations, missteps, governmental bureaucracy, and scholarly rivalries. Eight volumes were ultimately published in the Iowa-California edition of the Works of Mark Twain.

_____

The Iowa-California Works Volumes

Volumes in the Iowa-California edition of the Works of Mark Twain began issuing in 1972. The books feature volume numbers on the spine that indicated the approximate order in which Mark Twain published the work -- not the order in which the University of California Press published them. The volume numbers, prominent on the spines, reflect the hopes and dreams and visions of what a completed set might encompass. Collectors seeking a "complete set" who are not familiar with the publication history may find the volume numbers confusing. For example, as of the year 2012, Volume 1 has never been issued but Volume 19 was issued in 1973 and Volume 15 was issued in 1981.

_____

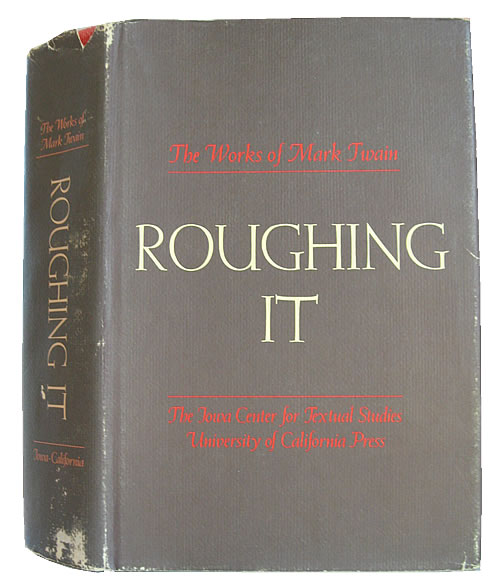

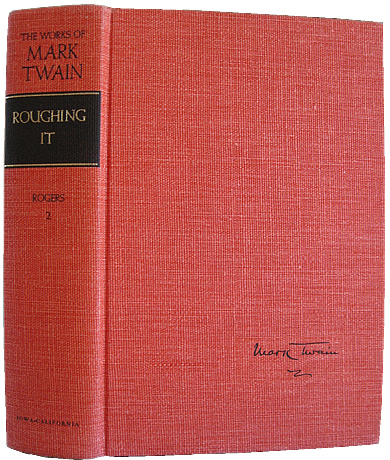

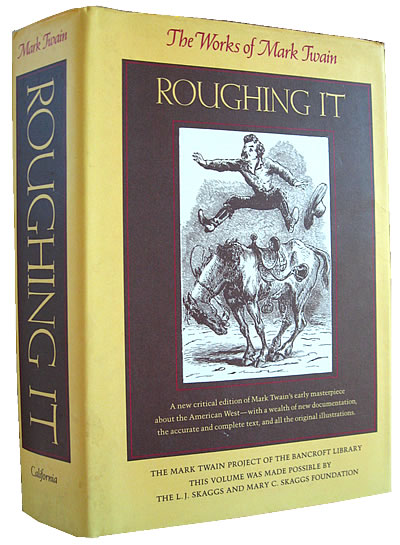

Volume 2 -Roughing It

1972 Edition

|

Bound in orange cloth, the 1972 Volume 2 of The Works of Mark Twain features editor Rogers's name on the spine along with Iowa-California |

Volume 2, Roughing It, issued in 1972, was the first volume issued in the Iowa-California edition. The introduction and explanatory notes were written by Franklin R. Rogers who had previously edited the Mark Twain Papers 1967 edition of Satires and Burlesques. The text of Roughing It was established by Paul Baender. The copyright page features the CEAA seal and an acknowledgment the volume was produced in cooperation with a contract from the United States Office of Education under the provisions of the Cooperative Research Program.

Editor Franklin R. Rogers (b. July 25, 1921 - d. Dec. 3, 2011) received his doctorate from the University of California at Berkeley on the G.I. Bill after serving in World War II. Rogers was teaching at the University of California at Davis at the time of his work on the Mark Twain editions. Rogers had no experience as a textual editor and the task of establishing authoritative texts fell to Paul Baender (b. December 1, 1926 - d. May 30, 2006), a self-trained textual editor. Baender also received his doctorate from Berkeley and for most of his career taught at the University of Iowa. The Rogers-Baender version of Roughing It features a full page frontispiece of Mark Twain but none of the original illustrations. Rogers and Baender simply eliminated any reference in Mark Twain's first edition text to the illustrations but noted these critical eliminations in explanatory notes. This edition of Roughing It was also issued by the University of California Press in softcover format minus the textual notes detailing how the text was established.

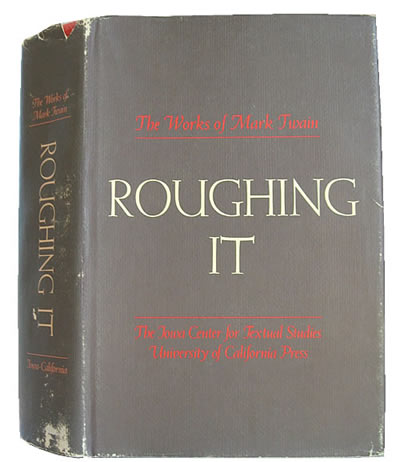

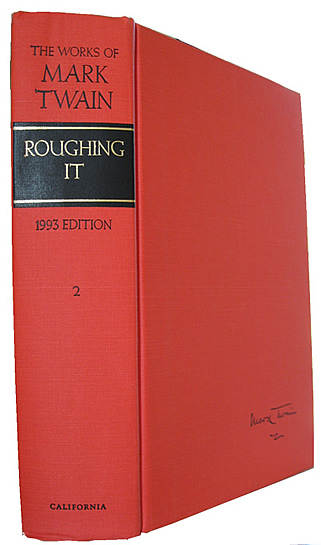

Volume 2 - Roughing It

1993 Revised California Edition

|

Bound in orange cloth, the 1993 Volume 2 of The Works of Mark Twain features California at the bottom of the spine |

Paul Baender's work on establishing the text of Roughing It was done at at time when the science of establishing authoritative texts of American authors was in early stages of development. Baender had not received formal training in textual editing, but was considered "self-taught." As textual analysis skills were developed by editors of the Mark Twain Papers at Berkeley, it became apparent that the 1972 edition of Roughing It did not measure up to scholarly expectations. New research was also producing more information about Mark Twain's time in the West that could be used to update Franklin Rogers's annotations. In 1993 a new edition of Roughing It was published by University of California Press that includes all of the original illustrations, revised annotations, and text that is in accordance with stricter standards for scholarly editions. References to Iowa on the spine and dust jacket were eliminated since in 1988 University of Iowa had ceased to make any contribution to the production costs of these books.

The 1993 Mark Twain Works edition of Roughing It published by the University of California Press features an acknowledgment that the volume was jointly supported by grants from the National Endowment for the Humanities as well as public and private donations. It features the Center for Scholarly Editions (CSE) seal on the copyright page. The volume was edited by Mark Twain Project editors Harriet Elinor Smith, Edgar Marquess Branch, Lin Salamo, and Robert Pack Browning. It was the winner of the 1993-94 Modern Language Association Prize for a Distinguished Scholarly Edition.

The volume was released in 1996 in a Mark Twain Library Edition -- an edition that features identical text and explanatory notes based on those featured in the Works edition but lacks the textual roadmap that explains to readers exactly how the authoritative text was established.

_____

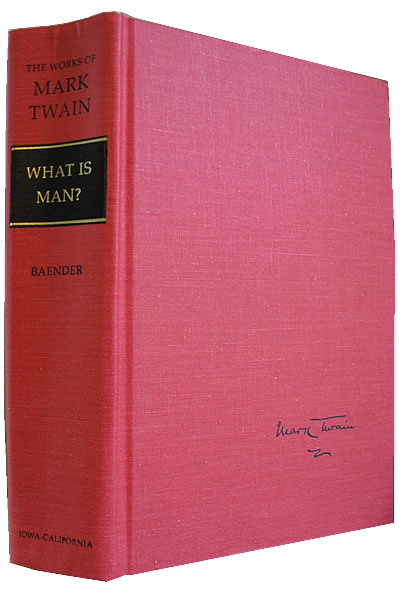

Volume 19 - What Is Man? and Other Philosophical Writings

1973

|

|

Bound in orange cloth, the 1973 Volume 19 of The Works of Mark Twain features editor Baender's name on the spine along with Iowa-California |

Volume 19, What Is Man? And Other Philosophical Writings issued in 1973, was the second volume issued in the Iowa-California edition. The introduction and explanatory notes were written by Paul Baender. The copyright page features the CEAA seal and an acknowledgment the volume was produced in cooperation with a contract from the United States Office of Education under the provisions of the Cooperative Research Program.

The contents of this volume differs radically from previous editions published under the similar title What Is Man? And Other Essays. The Iowa-California edition dropped almost all the essays that had been published in the earlier collection. Volume 19 focuses on philosophical and religious writings and includes Christian Science, a book that was issued as an individual volume in previous uniform editions. The Iowa-California volume also includes "Letters from the Earth" that had not been included in any previous uniform edition.

The Iowa-California edition of What Is Man? And Other Philosophical Writings blurred the line regarding the responsibilities and stated mission of the Works of Mark Twain project and the Mark Twain Papers project. While the Iowa editors continually emphasized their mission was to publish authoritative texts of previously published works, What Is Man? And Other Philosophical Writings features material never before previously published. At the time Frederick Anderson had not developed a plan to publish the entire body of Mark Twain's unpublished works and material relevant to previously published works was included in this volume. The essay "Things A Scotsman Want to Know" was included in the collection because it featured a theme closely tied to "Letters from the Earth." Discarded versions of other essays never before published are also included.

_____

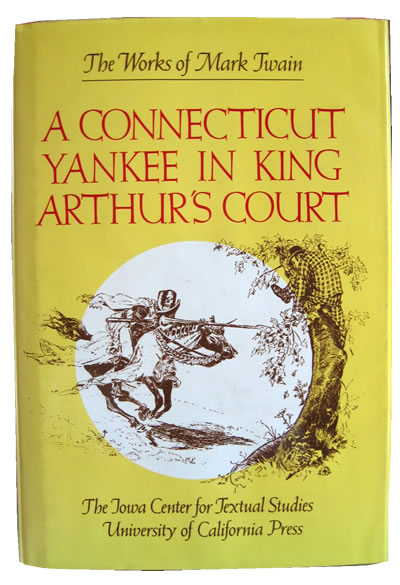

Volume 9 - A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court

1979

|

Bound in orange cloth, the 1979 Volume 9 of The Works of Mark Twain features the volume number on the spine. |

Volume 9, A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, was issued in the Works of Mark Twain edition in 1979. The original editor assigned to the volume, James D. Williams, had left the project. Bernard L. Stein, a Berkeley graduate student, was assigned the job of establishing the text and editing the work. Stein, a native of Riverdale, New York remained as an editor at the Mark Twain Project for twelve years after graduate school. (In 1998 Stein won the Pulitzer Prize for best editorial writing for his work at the Riverdale (NY) Press.) The introduction to A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court was written by Henry Nash Smith who returned to the Mark Twain Papers at Berkeley for a short time following the unexpected death of editor Frederick Anderson in January 1979. The title page features an acknowledgment the volume was made possible by a grant from the Editing Program of the National Endowment for the Humanities. The copyright page features the CSE seal. The volume contains all the illustrations from the first edition.

This volume was released in 1983 in a Mark Twain Library Edition -- an edition that features the identical text and explanatory notes based on those featured in the Mark Twain Works edition but lacks the textual roadmap that explains to readers exactly how the authoritative text was established.

_____

Volume 6 - The Prince and the Pauper

1979

|

Bound in orange cloth, the 1979 Volume 6 of The Works of Mark Twain features the volume number on the spine. |

Volume 6, The Prince and the Pauper, was issued in the Works edition in 1979. The original editor assigned to the volume, Roger B. Salomon, had left the project. The staff at the Mark Twain Papers in Berkeley edited the volume. The authoritative text was established by Victor Fischer. Lin Salamo wrote the explanatory notes and introduction to the volume. The title page features an acknowledgment the volume was made possible by a grant from the Editing Program of the National Endowment for the Humanities. The copyright page features the CSE seal. The volume retains all the illustrations from the first edition.

This volume was released four years later in 1983 in the Mark Twain Library Edition -- an edition that features identical text as that featured in the Works edition but lacks the textual roadmap that explains to readers exactly how the authoritative text was established. The explanatory notes originally written by Salamo were revised and supplemented by Michael B. Frank, an associate editor with the Mark Twain Project.

_____

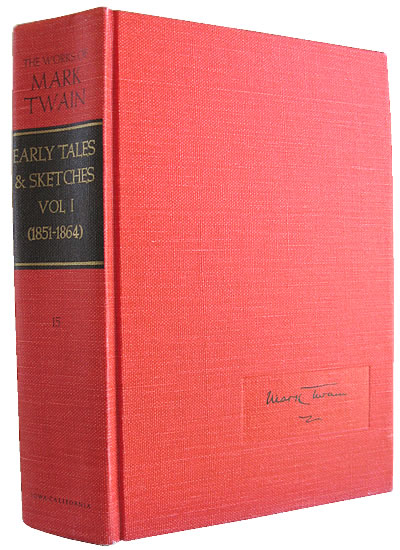

Volume 15 - Early Tales & Sketches, Volume 1, 1851-1864

1979

|

Bound in orange cloth, the 1979 Volume 15 of The Works of Mark Twain features the volume number 15 on the spine as well as Vol. 1 for the series of Early Tales & Sketches |

Volume 15, Early Tales & Sketches, Volume 1, 1851-1864, was issued in 1979. Edgar M. Branch, the original editor assigned to the volume, was assisted by Robert Hirst and Harriet Elinor Smith of the Mark Twain Papers staff at Berkeley. The introduction to the volume was written by Branch who dated it September 1977. The title page features an acknowledgment the volume was made possible by a grant from the Editing Program of the National Endowment for the Humanities. The copyright page features the CEAA seal. Since the CEAA seal had been replaced by the CSE seal in 1975, the use of the older seal indicates the text may have been established several years previous to actual publication.

This volume features 75 previously published sketches and newspaper contributions. These are numbered 1 - 75. Text printed on the jacket flap indicates the entire series of Early Tales & Sketches volumes would consist of 365 selections. Two appendixes feature a total of 22 attributed items that were likely written by Mark Twain although conclusive evidence in 1979 was lacking. Previously unpublished material includes "The Mysterious Murders in Risse," "Jul'us Caesar," and several poems.

_____

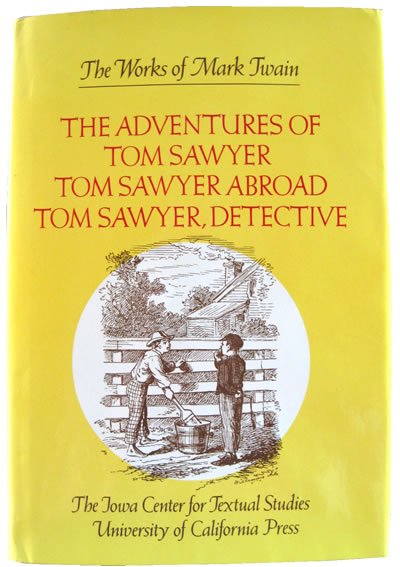

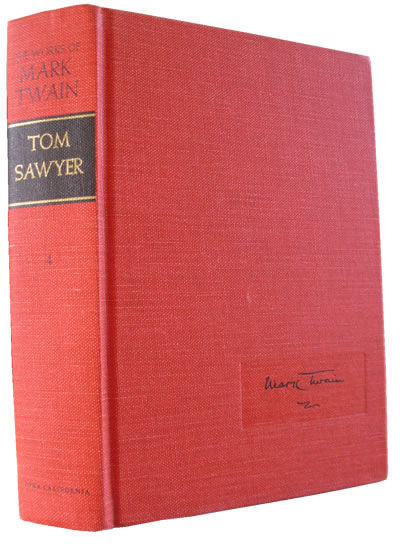

Volume 4 - The Adventures of Tom Sawyer / Tom Sawyer

Abroad / Tom Sawyer, Detective

1980

|

Bound in orange cloth, the 1980 Volume 4 of The Works of Mark Twain features the volume number 4 on the spine. |

Volume 4 in the Iowa-California Works edition is a collection of the three Tom Sawyer stories that were published in Mark Twain's lifetime plus "Boy's Manuscript" that was first published by Bernard DeVoto in 1942. The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Tom Sawyer Abroad, and Tom Sawyer, Detective had been profusely illustrated in their first edition publications. Editors John Gerber and Paul Baender eliminated the first edition illustrations and offered readers only a small sampling of the illustrations for The Adventures of Tom Sawyer in an appendix. The textual notes indicate that Baender, who served as textual editor, with the assistance of Iowa student Terry Firkins, frequently had difficulty deciphering Mark Twain's handwritten manuscripts. The copyright page features the CEAA seal, an indication the text had been approved several years prior to publication. The copyright page also notes that the research reported in the volume was performed pursuant to a contract with the United States Office of Education under the provisions of the Cooperative Research Program. Editorial expenses were supported in part by granted from the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Within two years of publication, Volume 4 was reworked by the Berkeley staff and the contents redistributed in separate volumes in the Mark Twain Library series -- editions featuring original illustrations, updated and corrected text, and explanatory notes but lack the textual roadmap of the Works edition.

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer and Tom Sawyer Abroad / Tom Sawyer, Detective were issued as two separate volumes in the Mark Twain Library series in 1982. John Gerber wrote new forewords for the two Mark Twain Library volumes. Robert Hirst provided short notes on the text and specified corrections he had made to the texts previously established by Paul Baender and Terry Firkins.

In 1989 "Boy's Manuscript" was corrected and included in the Mark Twain Library edition of Huck Finn and Tom Sawyer Among the Indians and Other Unfinished Stories. The end result being that the Mark Twain Library editions became the more reliable texts for all of the works included in Volume 4 of the Iowa-California Works edition.

_____

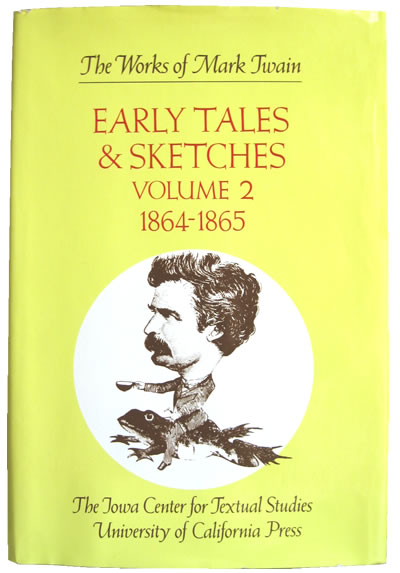

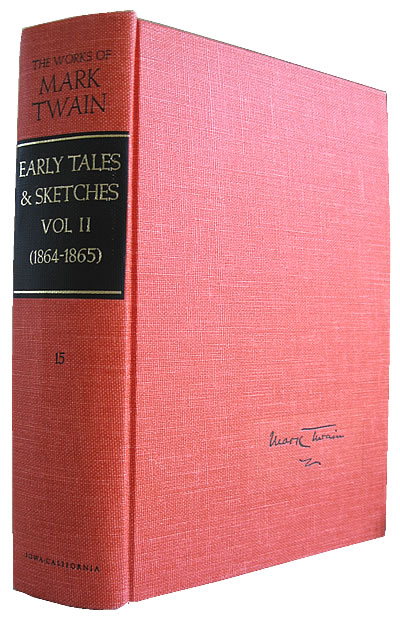

Volume 15 - Early Tales & Sketches, Volume 2, 1864-1865

1981

|

Bound in orange cloth, the 1981 edition of Early Tales & Sketches, Vol. 2 also features the volume number 15 on the spine -- the same volume number as Early Tales & Sketches, Vol. 1 that was issued in 1979. |

Volume 15, Early Tales & Sketches, Volume 2, 1864-1865, was issued in the Iowa-California Works edition in 1981. Edgar M. Branch, the original editor assigned to the volume, was assisted by Robert Hirst and Harriet Elinor Smith. The introduction to the volume was written by Branch and Hirst. The title page features an acknowledgment the volume was made possible by a grant from the Editing Program of the National Endowment for the Humanities. The copyright page features the CEAA seal. Since the CEAA seal had been replaced by the CSE seal in 1975, the use of the older seal indicates the text may have been established several years previous to actual publication.

The volume number 15 is the same volume number assigned to the 1979 edition of Early Tales & Sketches, Vol. 1 , 1851-1864. The duplicate volume numbers featured on both the spine and title pages can be a source of confusion for bibliographers and collectors. It is unclear whether or not all volumes that were projected for the Early Tales & Sketches series would be labeled volume 15. Text on the dust jacket from the previous 1979 volume indicates a total of 365 sketches were planned for the series. Text on the dust jacket from the 1981 volume indicates that number had risen to a projected 400 short works that would fill a total of five volumes of Early Tales & Sketches.

Early Tales & Sketches, Vol. 2 features 77 items primarily from Mark Twain's San Francisco newspaper contributions. The numbering sequence that began in Early Tales & Sketches, Vol. 1 is continued throughout the volume with sketches numbered 76-152. Two appendixes feature an additional 65 items attributed to Mark Twain but for which conclusive evidence is lacking. Previously unpublished material includes "Sarrozay Letter from 'the Unreliable,'" "The Mysterious Chinaman," and two unfinished drafts of the "Jumping Frog." A third appendix features fragments from two manuscripts that were never previously published.

No additional volumes in the series of Early Tales & Sketches were ever published.

_____

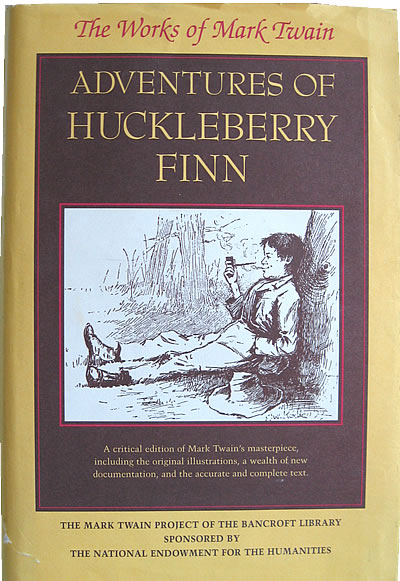

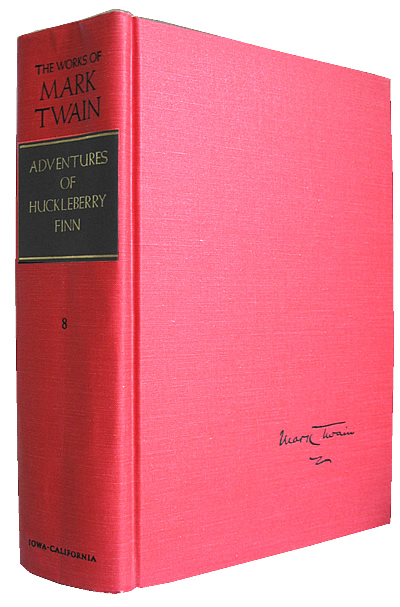

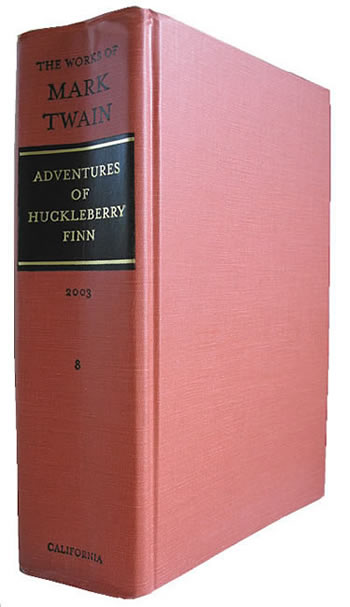

Volume 8 - Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

1988

|

Bound in orange cloth, the 1988 edition of Adventures of Huckleberry Finn features the volume number 8 and Iowa-California on the spine. |

Volume 8, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, was the final title issued in the Iowa-California Works series. It was edited by Walter Blair of the University of Chicago who also wrote the introduction. Victor Fischer of the Berkeley Mark Twain Project staff served as coeditor with the assistance of Dahlia Armon and Harriet Elinor Smith. Blair's previous publications included Mark Twain & Huck Finn (University of California Press, 1960). In 1969 Blair had edited Hannibal, Huck, & Tom, a collection of previously unpublished essays and manuscripts in the Mark Twain Papers series. The publication of this Works volume had been preceded by the Mark Twain Library edition of Adventures of Huckleberry Finn in 1985 -- a reversal of the previous publication schedules when the Library editions had followed the scholarly Works editions. Preliminary pages for the volume indicate the editorial work was made possible in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. The copyright page features the CSE seal. The 1988 Works edition features the same authoritative text and explanatory notes as those featured in the Mark Twain Library edition plus substantial textual notes indicating how the authoritative text was established.

_____

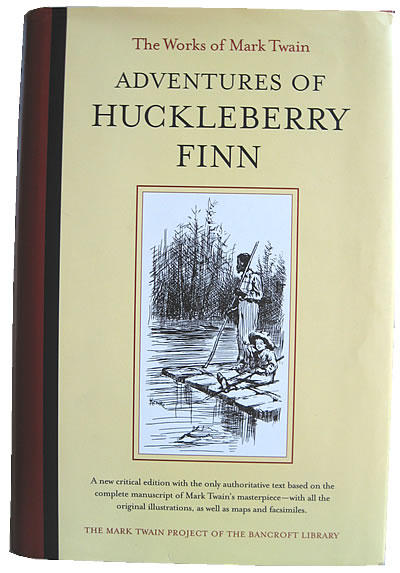

Volume 8 - Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

2003 Revised California Edition

|

Bound in dark tan cloth, the 2003 edition of Adventures of Huckleberry Finn features volume number 8 and California on the spine . |

The 1988 Iowa-California edition of Adventures of Huckleberry Finn was published without benefit of access to the handwritten manuscript of the first half of the novel that was presumed lost. In 1988 the likelihood of recovery or finding the missing manuscript was unimaginable. However, in October 1990, the remarkable discovery of the missing first half of the Huckleberry Finn manuscript in the attic of Barbara Gluck Testa, a descendant of a Buffalo, New York librarian rendered all previous scholarly editions of the novel obsolete. However, it would be another eleven years after the discovery before details regarding the composition of the first half of the novel were published in the Mark Twain Library Edition in 2001. The Works edition followed in 2003 with the extensive textual analysis that had become a hallmark of the previous scholarly editions.

Walter Blair, the original editor died in 1992. Editors for the revised edition were Victor Fischer and Lin Salamo with the assistance of Harriet Elinor Smith. The title page acknowledges the late Walter Blair whose previous research had been a foundation of the 1988 edition. Editorial work for the volume was supported in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. The volume features the CSE seal on the copyright page. References to the Iowa-California partnership do not appear on the title pages and spine.

_____

Volumes Published Elsewhere

Three volumes originally intended for publication in the Iowa-California Works of Mark Twain series were published elsewhere.

Mark Twain Speaking (1976)

Paul Fatout was the editor originally assigned to edit a volume of Mark Twain's speeches. No authoritative text could be found for many speeches. These speeches existed only as newspaper transcriptions. According to Fatout, he "soon realized, with dismay, that he could not be certain of exactly what Mark Twain said on any occasion." It would be impossible for the volume to receive CEAA or CSE certifications. Fatout's volume of Mark Twain Speaking was published by the University of Iowa Press in 1976 and reissued in 2006. It remains one of the best reference books available for texts of Mark Twain speeches.

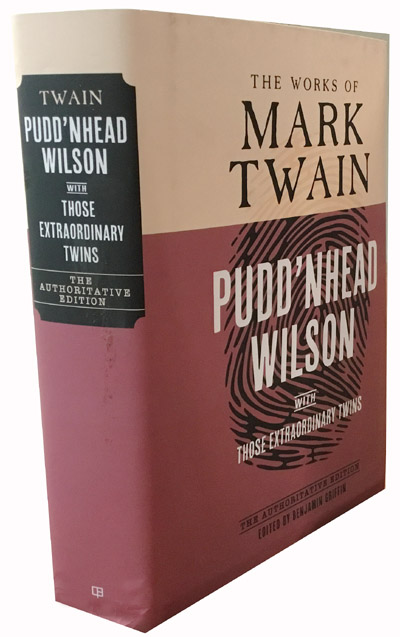

Pudd'nhead Wilson and Those Extraordinary Twins (1980, 2005)

Arlin Turner was the editor originally assigned to edit Pudd'nhead Wilson and Those Extraordinary Twins for the Iowa-California Works series. Turner had been replaced by Sidney E. Berger who worked on the texts about ten years before publishing his authoritative text with textual notes and criticism as a Norton Critical Edition in 1980. Berger's Norton Critical Edition was reissued in 2005. It remained the most comprehensive study of that text until 2024 when a new California Works edition of Pudd'nhead Wilson was published (see below). Hershel Parker was the next editor to get the assignment to edit an edition of Pudd'nhead Wilson for the University of California Works edition. Parker left the project in 1984 "for other reasons." In 1984 Parker published Flawed Texts & Verbal Icons, an iconoclastic work that addressed a number of problematic issues regarding Mark Twain's Pudd'nhead Wilson text and its composition.

The Bible According to Mark Twain (1995)

Howard Baetzhold was the editor who was charged with editing a volume of short fiction from the middle and late stages of Mark Twain's career for the Iowa-California edition. Baetzhold was later joined by Joseph McCullough in the endeavor to produce a volume that focused on Mark Twain's writings on Adam and Eve, Captain Stormfield, and "Letters From the Earth." A number of previously unpublished manuscripts related to these writings were also included. Baetzhold and McCullough expanded on the annotations that Baender had offered in his version of "Letters From the Earth" that was previously included in Baender's What Is Man? And Other Philosophical Writings issued in 1973. The Bible According to Mark Twain was published by University of George Press in 1995 and remains the most authoritative text for works that had appeared under the titles Adam's Diary, Eve's Diary, Captain Stormfield's Visit to Heaven and Letters from the Earth.

_____

Why the Iowa-California Works Edition Fell Short

The Iowa-California Works of Mark Twain failed to meet the goal of publishing more than twenty scholarly volumes because:

Only eight volumes were published in the Iowa-California Works edition -- about a third of the number originally proposed. Most of the volumes that were released are considered the most authoritative texts ever published for those particular titles.

_____

California Works Volumes (1993 - ongoing)

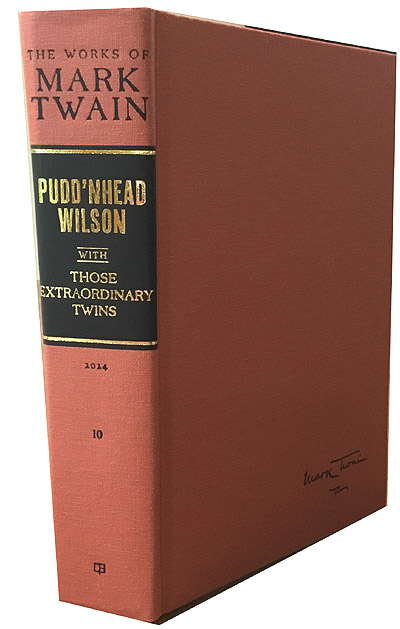

Volume 10 - Pudd'nhead Wilson: Manuscript and Revised Versions, with "Those Extraordinary Twins" (2024)

|

Bound in dark tan cloth, the 2024 edition of Pudd-nhead Wilson features the year 2024, volume 10, and the logo for University of California Press on the spine. |

Pudd'nhead

Wilson (2024) features the updated CSE seal of approval on the copyright

page.

As noted above, after the collapse of the Iowa-California project, the University of California continued issuing Works editions from the University of California Press. The first, in 1993, was an updated edition of the old Iowa-California Volume 2 - Roughing It. This was followed in 2003 an updated edition of Volume 8 - Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. After a hiatus of over twenty years between Works editions, Volume 10, Pudd'nhead Wilson: Manuscript and Revised Versions, with "Those Extraordinary Twins," edited by Benjamin Griffin of the Mark Twain Project, was issued in 2024. This Works edition of Pudd'nhead Wilson features the original manuscript of Pudd'nead Wilson known as the "Morgan manuscript," a work that Mark Twain considered complete but was never published due to financial constraints and the collapse of his own publishing company, Webster and Company. The volume also includes the text of the manuscript that Mark Twain revised for serial publication in Century Magazine. In addition, it includes "Those Extraordinary Twins," a segment that was first issued in book format by American Publishing Company under the title The Tragedy of Pudd'nhead Wilson and the Comedy Extraordinary Twins. Illustruations for this edition include those by Louis Loeb that Mark Twain had approved for the Century Magazine serialization.

More California Works Editions are planned. Publication schedules for forthcoming volumes are determined by a variety of factors including funding.

_____

Summary of Features

_____

Baender, Paul and Frederick Anderson, "Twain in Progress: Two Projects," American Quarterly, Winter 1964, pp. 621-623.

Brack, O M Jr., and Warner Barnes. Bibliography and Textual Criticism: English and American Literature, 1700 to the Present, (University of Chicago Press, 1969).

Costa, Richard Hauer. Edmund Wilson: Our Neighbor from Talcottville, (Syracuse University Press, 1980).

"Edmund Wilson Dies," The New York Times, 13 June 1972. Accessed 30 May 2012.

Gerber, John C. "The Iowa Years of The Works of Mark Twain: A Reminiscence," Studies in American Humor, ser. 3, no. 4, (1997), pp. 68 - 87.

"Harper Merging with Text House," The New York Times, 2 November 1961.

Hirst, Robert. Personal correspondence, 29 April 2012.

_____. Personal correspondence, 30 May 2012 and 1 August 2012.

_____. "Textual Editing at the Mark Twain Project: A Brief Account." Accessed 28 May 2012.

Mark Twain Papers and Project: A Brief History. Accessed 30 May 2012.

Menand, Louis. "A Critic at Large / Missionary / Edmund Wilson and American Culture," The New Yorker, 8 August 2005. Accessed online 29 May 2012.

Parker, Hershel. Flawed Texts and Verbal Icons: Literary Authority in American Fiction, (Northwestern University Press, 1984).

_____. Personal correspondence, 25 July 2012.

Professional Standards and American Editions: A Response to Edmund Wilson. (Modern Language Association of America, 1969).

Wilson, Edmund. The Fruits of the MLA. A New York Review Book (December 1968).