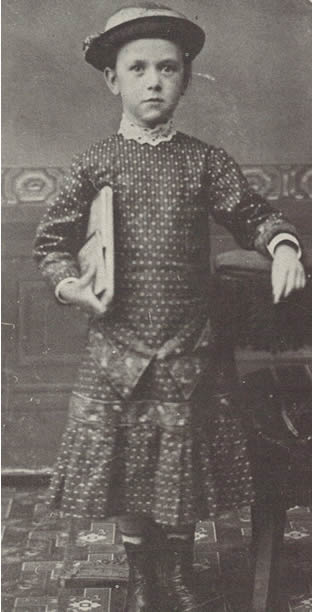

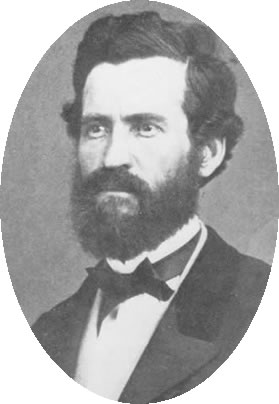

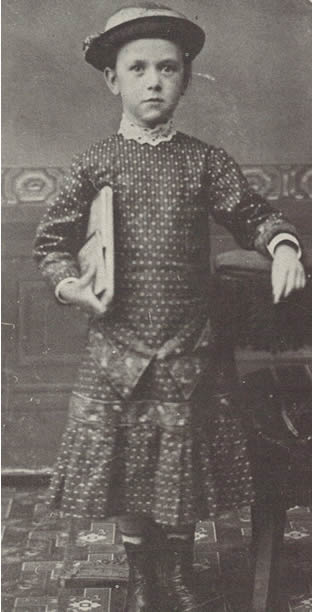

Jennie

Clemens, (1855 - 1864)

Samuel Clemens's niece |

MARK TWAIN'S QUARREL

WITH

UNDERTAKERS:

It All Begins with

Jennie

"Tragedy always leaves a psychic scar upon a site, and there

is nothing so heart-rending as the death of a beloved child." -

Richard Senate,

historian and author

|

_____

Introduction

"Let us endeavor so to live that when we come to die even

the undertaker will be sorry." Samuel Clemens included that maxim in

"Pudd'head Wilson's Calendar" in 1894. At first glance the famous

quote appears humorous, motivating and encouraging the reader to live a life

filled with good deeds. But there is a darker side to the quote that reveals

a resentment Sam Clemens held for the occupation of undertakers -- men who

made their living by taking advantage of sorrow. This was a view he formulated

in 1864 when he lived in the territory of Nevada and a view that he would

continually express throughout his lifetime.

The Clemens Family Goes West

Samuel Clemens and his older brother Orion left St. Louis, Missouri

on July 18, 1861 enroute to the territory of Nevada. Abraham Lincoln had been

inaugurated as president of the United States on March 4, 1861 and Orion,

who had actively campaigned for Lincoln had received a political appointment

as secretary of Nevada territory. Sam had been a Mississippi steamboat pilot

until the Civil War broke out a few months earlier and closed down commerce

and travel on the great river. Sam had agreed to pay the travel passage for

them both from Missouri to Nevada when Orion promised to make Sam his personal

secretary -- an unfunded position. The brothers traveled by steamboat up the

Missouri River to Saint Joseph, Missouri. At St. Joseph they boarded a stagecoach

headed for Carson City, seventeen hundred miles west. Orion was leaving behind

a string of unprofitable jobs as a newspaper editor, publisher and printer

in Missouri and Iowa in hopes of finally finding a meaningful occupation in

government service in Nevada territory.

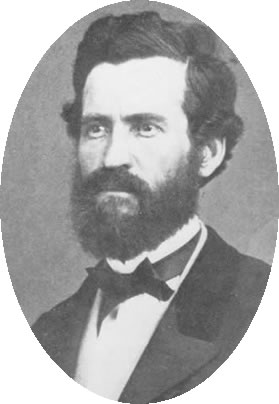

Mollie

Stotts Clemens

|

Orion

Clemens |

Orion had married Mary Eleanor "Mollie" Stotts of

Keokuk, Iowa in December 1854 and their daughter Jennie was born the following

September 1855. Orion had requested an advance on his future salary of $1,800

a year in order to take Mollie and Jennie with him to Carson City that summer

in 1861. The request for a salary advance was denied and it would be October

1862 before Mollie and Jennie would make the trip to Nevada and reunite the

family. At the first territorial legislative session in 1861, the legislators

passed a law enabling Orion to collect fees for providing certified documents,

copies of laws, and filing certificates of incorporation. The added income

enabled Orion to erect one of the finest homes in Carson City at the corner

of Spear and Division street. The two-story home with a circular porch and

bay window was constructed for $12,000, a princely sum in the 1860s. Orion

furnished the home with walnut furniture, a grand piano, and a special little

rocking chair for Jennie. The home soon became a social center for the town

as Mollie became a well-loved and popular hostess.

The home

Orion Clemens built for Mollie and Jennie still stands in Carson City, Nevada.

Photo © R. Kent Rasmussen, 2002.

_____

Jennie Clemens -- "A Heaven Born Child"

Orion and his family joined the First Presbyterian Church of

Carson City and worked to raise money for a new church building. Jennie worked

to raise money to buy the church a Bible for the pulpit. She attended school

at Miss Hannah Keziah Clapp's Sierra Seminary. By all accounts she was bright

and loved to read the family Bible. She told Mollie she often prayed at school

for assistance when she had difficulties. Her parents told friends that Jennie

had read Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress. Family friend and newspaper reporter

Dan DeQuille, a frequent visitor in Orion's home, told of Jennie's joy of

reading:

I was amused by a little daughter of his who was turning over the leaves

of a work on geography, suddenly starting up and exclaiming gleefully, --

'Good, good! I have found it! I've found it at last!' Found what?' her father

asked. 'Why look there -- "God fishing off New Foundland"! He

looked and read under a picture, 'Cod Fishing off New Foundland.' (Mack,

Nevada Historical Society Quarterly, p.93).

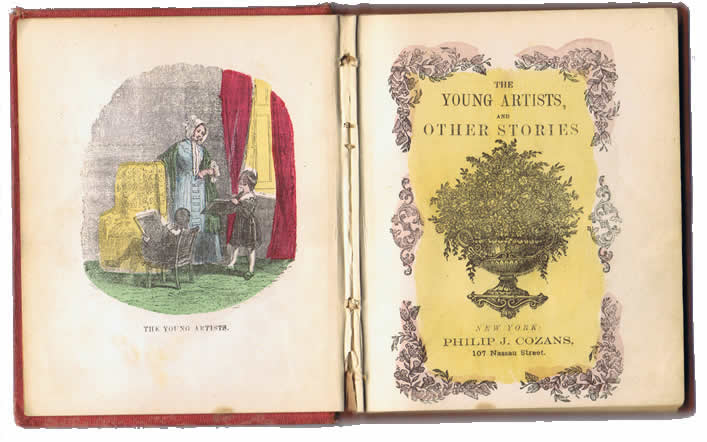

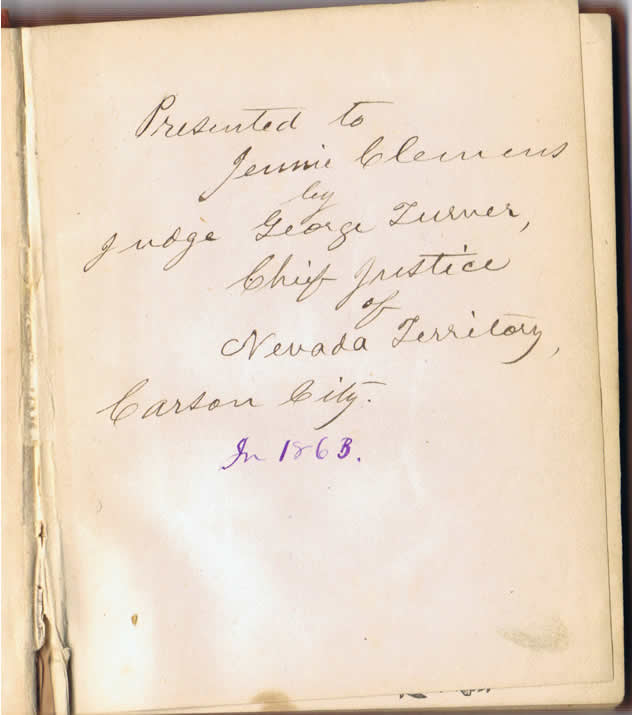

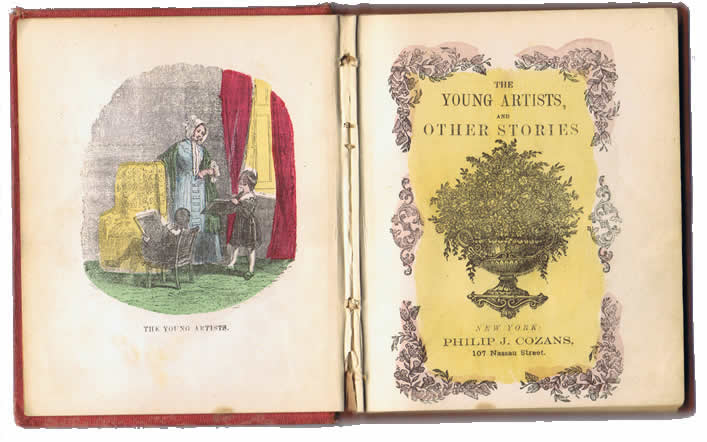

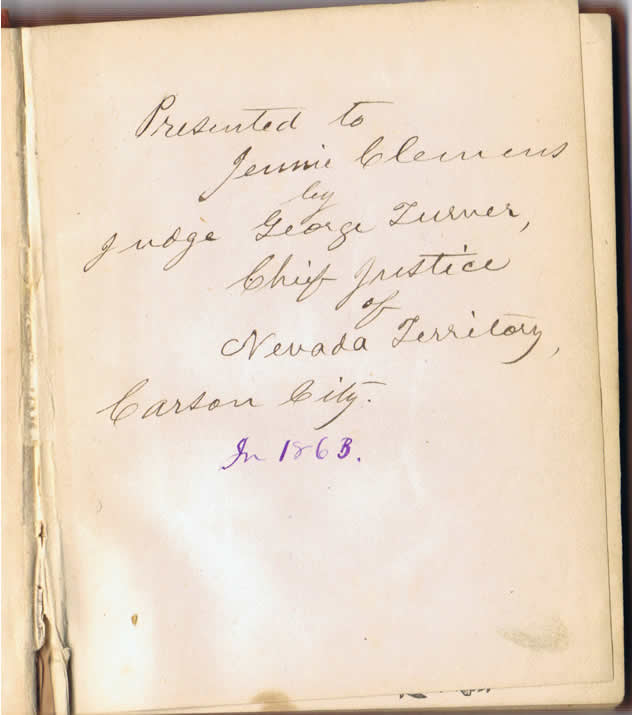

Among the few surviving items once owned by Jennie Clemens is her copy of

a book titled The Young Artists, and Other Stories that was presented

to her by Judge George Turner, Chief Justice of Nevada Territory in 1863.

Jennie's

book was given to Sam's daughter Clara Clemens in 1880 by Orion and Mollie.

The book is now in the Kevin Mac Donnell collection.

Photos courtesy of Kevin Mac Donnell.

_____

Mark Twain, Influential Newspaper Reporter

After the first territorial legislative session ended in late

1861 Sam, who had received a few month's salary for serving as a legislative

clerk, drifted into silver mining in the nearby regions. Unable to strike

it rich, in August 1862 Sam accepted a position as a reporter for the Territorial

Enterprise in Virginia City, about fifteen miles northeast of Carson City.

When the second territorial legislature convened in November 1862, Sam traveled

to Carson City as a reporter covering the proceedings and lodged with Orion,

Mollie and Jennie.

When he wasn't reporting on the territorial legislature, Sam

Clemens wrote local news stories about Virginia City and Carson City. On

January 31, 1863 Sam Clemens, writing from Carson City to the Territorial

Enterprise, signed his story "Mark Twain." It is the first

known usage of his famous pen name and some historians theorize the name was

invented in Jennie's bedroom.

When there wasn't a lot of news to be found, Sam Clemens manufactured

it. Gold mines, massacres, and petrified men were only a few of the topics

and hoaxes he wrote about. Descriptions and good-natured jokes related to

undertakers were common. When John Van Buren Perry was elected City Marshall

of Virginia City in the spring of 1863, Sam wrote about the size of his wooden

shoes:

In 1835, during a great leather famine, many people were obliged to wear

wooden shoes, and Mr. Perry, for the sake of economy, transferred his boot-making

patronage from the tan-yard which had before enjoyed his custom, to an undertaker's

establishment -- that is to say, he wore coffins ("City

Marshall Perry," Territorial Enterprise, March 3, 1863.)

In August 1863 he visited the curative hot mineral waters at Steamboat Springs

near Virginia City, known for their medicinal properties. He described miners

who visited the springs hoping for a cure:

More than two-thirds of the people who come here are afflicted

with venereal diseases -- fellows who know that if "Steamboat" fails

with them they may as well go to trading feet with the undertaker for a box

-- yet all here agree that these baths are none the less potent where other

diseases are concerned (

"Letter

from Mark Twain," Territorial Enterprise, August 25, 1863).

Sam spent time in Orion's home over the next year, sometimes

walking the distance from Virginia City to Carson City, and writing up local

news reports as Nevada transformed itself from a territory into a state. When

the constitutional convention was in session from November to December 1863

Sam was again on hand to report the proceedings. With his brother Orion installed

as secretary of Nevada territory, Sam's unmatchable writing skills, and his

position writing for the most influential paper in Nevada, Sam Clemens wielded

considerable influence. Sam's official biographer Albert Bigelow Paine claimed

that Sam "could control more votes than any legislative member, and with

his friends ... could pass or defeat any bill offered" (Paine, p. 244).

He used his influence to aid causes that were special to Orion and his family.

On December 5 he reported on the fund raising activities for the new

church in Carson City, a cause that was dear to Mollie and Jennie.

In January 1864 Sam visited Jennie's school Miss Clapp's Sierra

Seminary. In a report published in the Territorial Enterprise and dated

January 14, Sam lobbied the territorial legislators to continue their funding

for the school. No doubt, little Jennie was in attendance the day her uncle

Sam visited and took much delight in later reading his playful newspaper report

which described her classmates' activities that day. The article titled "Miss

Clapp's School" contains numerous parallels to the descriptions of

students and classrooms Clemens would later employ in his novel The Adventures

of Tom Sawyer. On January 27, 1864 Sam Clemens delivered one of his earliest

public speeches at the Carson City courthouse. The audience was charged a

dollar admission -- the funds raised, approximately $200, were to be used

to benefit the new Presbyterian church under construction. Sam wrote about

the speech the next day for a report

published in the Territorial Enterprise. (A photo of the church

is online at Western

Nevada Historic Photo Collection.)

_____

Death of Jennie Clemens - A "Signal Event"

Tragedy struck the Clemens family two days after Sam delivered

his church fundraising speech. On January 29, eight-year-old Jennie was stricken

with spotted fever. In her delirium she repeated the Lord's Prayer while Sam,

Orion and Mollie kept watch at her bedside. Jennie, an only child, died at

6 PM on February 1, 1864. Jennie was buried at 10 AM on February 3 and the

territorial legislature adjourned to attend the funeral. When news of Jennie's

death reached her grandmother Jane Clemens, Jane wrote to Mollie and Orion,

"Jennie was an uncommon smart child she was a very handsome child but

I never thought you would raise her, she was a heaven born child, she was

two [sic] good for this world" (Fanning, p. 91). Several years later

Mollie would chastise herself writing, "I know it is best she were taken.

I was not fit to bring her up" (Fanning, p. 91). Philip Fanning, Orion's

biographer has described Jennie's death as a "signal event" in the

lives of the family -- an event that has been largely overlooked by previous

biographers. Jennie's death spelled the end of a way of life Orion and Mollie

had come to love -- the couple remained childless thereafter and Orion's political

career declined into nothingness. Jennie's uncle Sam Clemens would grieve

in his own way and take from Jennie's death a particular view of undertakers

that would permeate through his stories, books and letters as Mark Twain lashed

out at the men who turned a profit from sorrow and death.

Jennie Clemens

grave marker at plot 1E-07-06 in Lone Mountain Cemetery (also known as Wright

Cemetery) in Carson City, Nevada.

Photo courtesy of Bob Wilkie, 2008 randomnevadablogspot.com

Jennie's marker was provided by Abraham Curry, a leading citizen of Carson

City at the time of her death.

Jennie's grave continues to be maintained by local residents.

Photo courtesy of Bob Wilkie, 2008 randomnevadablogspot.com

_____

Mark Twain and the Carson City Undertaker - February 1864

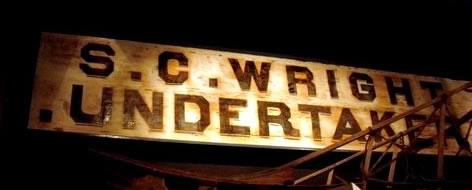

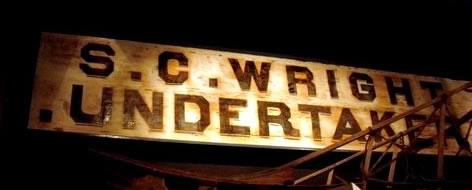

The undertaker for Carson City, Nevada in 1864 was Samuel C.

Wright. Wright was born in Syracuse, New York April 3, 1831 and had gone west

as a young man, settling first in Downieville, California. He relocated to

Carson City in the early 1860s. Embalming practices were not widely practiced

until after the Civil War and at the time of Jennie's death the process of

burial would have included building a coffin, transporting the body, and a

providing a burial location. The 1870 census for Carson City lists the occupation

of S. C. Wright, not as an undertaker, but as a "joiner" -- a carpentry

trade. Also living in the same household with Wright in 1870 was David Riley,

a cabinet maker. In the 1880 census for Carson City, Wright was listing his

occupation as a carpenter.

S. C. Wright

Undertaker sign was found in the attic of a home in Carson City, Nevada which

was being torn down in the 1990s. It is now in the Nevada State Museum. Photo

courtesy of Bob Wilkie, 2010 randomnevadablogspot.com

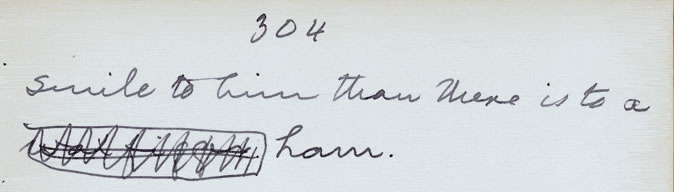

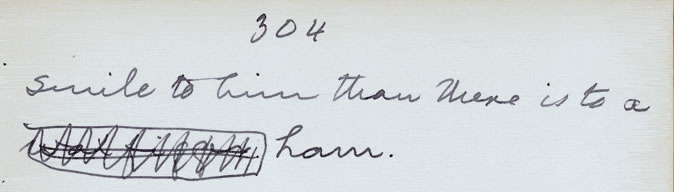

Four days after Jennie's death, in a letter to the Territorial

Enterprise dated

February 5, 1864 and published February 12 Sam Clemens lashed out at the

Carson City undertaker for extortion and taking advantage of people in sorrow.

He also took aim at a local newspaper, the Carson City Independent for

tolerating the practices of the undertaker without complaint. In an item titled

"Concerning

Undertakers" he wrote:

There is a system of extortion going on here which is absolutely terrific,

and I wonder the Carson Independent has never ventilated the subject.

There seems to be only one undertaker in the town, and he owns the only

graveyard in which it is at all high-toned or aristocratic to be buried.

Consequently, when a man loses his wife or his child, or his mother, this

undertaker makes him sweat for it. I appeal to those whose firesides death

has made desolate during the few fatal weeks just past, if I am not speaking

the truth. Does not this undertaker take advantage of that unfortunate delicacy

which prevents a man from disputing an unjust bill for services rendered

in burying the dead, to extort ten-fold more than his labors are worth?

I have conversed with a good many citizens on this subject, and they all

say the same thing: that they know it is wrong that a man should be unmercifully

fleeced under such circumstances, but, according to the solemn etiquette

above referred to, he cannot help himself. All that sounds very absurd to

me. I have a human distaste for death, as applied to myself, but I see nothing

very solemn about it as applied to anybody -- it is more to be dreaded than

a birth or a marriage, perhaps, but it is really not as solemn a matter

as either of these, when you come to take a rational, practical view of

the case. Therefore I would prefer to know that an undertaker's bill was

a just one before I paid it; and I would rather see it go clear to the Supreme

Court of the United States, if I could afford the luxury, than pay it if

it were distinguished for its unjustness. A great many people in the world

do not think as I do about these things. But I care nothing for that. The

knowledge that I am right is sufficient for me. This undertaker charges

a hundred and fifty dollars for a pine coffin that cost him twenty or thirty,

and fifty dollars for a grave that did not cost him ten -- and this at a

time when his ghastly services are required at least seven times a week.

I gather these facts from some of the best citizens of Carson, and I can

publish their names at any moment if you want them. What Carson needs is

a few more undertakers - there is vacant land enough here for a thousand

cemeteries.

If Clemens's account of Carson City undertaking prices are taken literally,

Jennie's funeral cost $200 -- a little over $3,000 in year 2007 dollars. No

records have been found that indicate the cost of Jennie's funeral was a financial

burden on the family but in all likelihood that may have been the case and

the source of Clemens's indignation. There is no surviving record that indicates

Samuel C. Wright ever responded to Clemens's charges in a public manner. However,

the Carson City Independent newspaper did step forward to defend their

paper the following day in an editorial. On

February 13, Mark Twain sent a copy of the Independent's reply to the

Territorial Enterprise.

EDITORS

ENTERPRISE: The

Independent takes hold

of a wretched public evil and shakes it and bullyrags it in the following

determined and spirited manner this morning:

"Our friend, Mark Twain, is such a joker that we cannot tell when

he is really in earnest. He says in his last letter to the ENTERPRISE,

that our undertaker charges exorbitantly for his services - as much as $150

for a pine coffin, and $50 for a grave and is astonished that the Independent

has not, ere this, said something about this extortion. As yet we have had

no occasion for a coffin or a bit of ground for grave purposes, and therefore

know nothing about the price of such things. If any of our citizens think

they have been imposed upon in this particular, it is their duty to ventilate

the matter. We have heard no complaints."

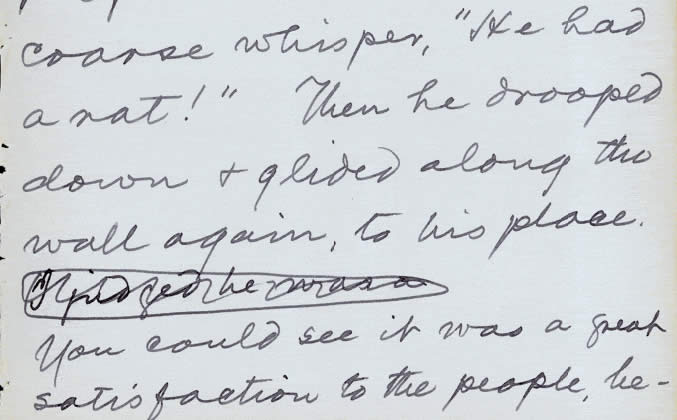

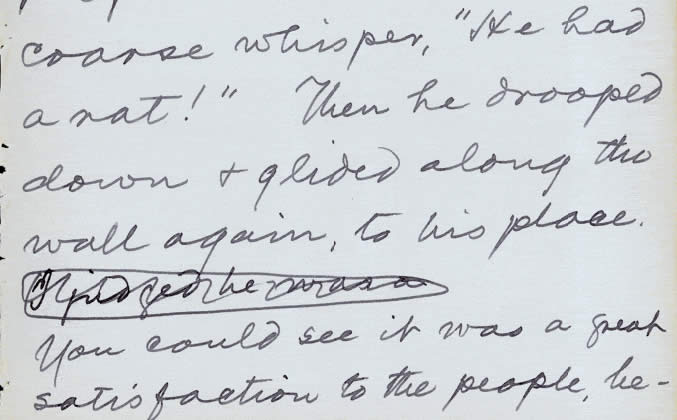

Clemens's rage and invective against the Independent and the Carson

City undertaker were unrestrained in his response. In an article titled "The

Carson Undertaker - Continued" he accused the Independent

of having::

... insipid chalk-milk editorials, defending the abuse and apologizing

for the perpetrator of it; or when public sentiment is too well established

on the subject, pretending, as in the above case, that you are the only

man in the community who don't know anything about it. Where did you get

your notion of the duties of a journalist from? Any editor in the world

will say it is your duty to ferret out these abuses, and your duty to correct

them. What are you paid for? what use are you to the community? what are

you fit for as conductor of a newspaper, you cannot do these things? Are

you paid to know nothing, and keep on writing about it every day? How long

do you suppose such a jack-legged newspaper as yours would be supported

or tolerated in Carson, if you had a rival no larger than a foolscap sheet,

but with something in it, and whose editor would know, or at least have

energy enough to find out, whether a neighboring paper abused one of the

citizens justly or unjustly? That paragraph which I have copied, seems to

mean one thing, while in reality it means another. It's true translation

is, for instance: "Our name is Independent -- that is, in different

phrase, Opinionless. We have no opinions on any subject -- we reside permanently

on the fence. In order to have no opinions, it is necessary that we should

know nothing -- therefore, if this undertaker is fleecing the people, we

will not know it, and then we shall not offend him. We have heard no complaints,

and we shall make no inquiries, lest we do hear some." ...

In the same article he continued to take the Independent to task charging:

... wilfully see no wrong in this undertaker's impoverishing charges for

burying people -- charges which are made simply because, from the nature

of the service rendered, a man dare not demur to their payment, lest the

fact be talked of around town and he be disgraced. ...

The editor of the Independent says he don't know anything about

this undertaker business. If he would go and report a while for some responsible

newspaper, he would learn the knack of finding out things. Now if he wants

to know that the undertaker charged three or four prices for a coffin (the

late Mr. Nash's) upon one occasion, and then refused to let it go out of

his hands, when the funeral was waiting, until it was paid for, although

the estate was good for it, being worth $20,000 -- let him go and ask Jack

Harris. If he wants any amount of information, let him inquire of Curry,

or Pete Hopkins, or Judge Wright. Stuff! let him ask any man he meets in

the street -- the matter is as universal a topic of conversation here as

is the subject of "feet" in Virginia. But I don't suppose you

want to know anything about it. I want to shed one more unsolicited opinion,

which is that your Independent is the deadest, flattest, [most] worthless

thing I know -- and I imagine my cold, unsmiling undertaker has his hungry

eye upon it.

Mr. Curry says if the people will come forward and take hold of the matter,

a city cemetery can be prepared and fenced in a week, and at a trivial cost

- a cemetery from which a man can set out for Paradise or perdition just

as respectably as he can from the undertaker's private grounds at present.

Another undertaker can then be invited to come and take charge of the business.

Mr. Curry is right -- and no man can move in the matter with greater effect

than himself. Let the reform be instituted.

Taken as a whole, Clemens's rampage in print against the Carson City undertaker

and the editor of the Carson City Independent was a reaction to the

grief he was feeling at the loss of Jennie Clemens. Evidence also exists that

the editor of the Independent, Frances Dallam, a former major in the

Civil War, understood the source of this outrage. On February

17, Mark Twain sent the following dispatch to the Enterprise from

Carson City:

Dallam, of the Carson Independent, makes a full and unqualified

apology to me this morning -- an entire column of it. He says he was not

in his right mind at the time, and hardly ever is. Now, when a man comes

out like that, and owns up with such pleasant candor, I think I ought to

accept his apology. Consequently, we will call it square. It is flattering

to me to observe that Dallam's editorials display great ability this morning,

and that the paper shows an extraordinary degree of improvement in every

respect. A becoming modesty should characterize us all -- it is not for

me to say who the credit is due to for the improvements mentioned. I only

say I am glad to see the Independent looking healthy and vigorous

again. -- MARK

No copy of the Carson City Independent for February 17, 1864 has apparently

survived. Thus, the exact nature of Major Dallam's apology to Clemens remains

unknown. Did Dallam acknowledge the death of Jennie Clemens and the fact that

Clemens was lashing out at the undertaker in his grief? The question remains

unanswered. Frances Dallam later moved from the Carson City Independent

to take a position with the Virginia City Daily Union newspaper. In

the fall of 1865 Dallam left Nevada and returned to his home state of Illinois.

Dallam was writing for the Quincy (Illinois) Whig in April 1867

when Mark Twain, who was beginning to earn fame as a lecturer, was scheduled

to speak in Quincy concerning his recent voyage to the Sandwich Islands. Dallam

wrote a warm and flattering editorial about his former newspaper rival in

advance of Clemens's appearance.

The other target of Clemens's rage -- Samuel C. Wright, the Carson City undertaker,

survived the storm of bad publicity. He became active in Nevada politics.

In 1869 he was appointed Receiver of the U.S. Land Office at Carson. In July

1889 he was appointed by U.S. President Harrison as Superintendent of the

United States Mint at Carson City. He held that position until his death in

1892.

The following month after Clemens's outburst in print about the Carson City

undertaker and the Independent, Sam wrote his sister Pamela from Virginia

City on March 18, 1864, "Molly & Orion are all right, I guess. They

would write me if I would answer there [sic] letters -- but I won't. It is

torture to me to write a letter. And it is still greater torture to receive

one -- except yours & Ma's (Letters, Vol. 1, p. 275-6).Unable to

earn a living in Nevada's government service, Orion and Mollie Clemens left

Nevada in August 1866. They sold their Carson City home at a loss and returned

to Mollie's hometown of Keokuk, Iowa. Over the ensuing years Orion's economic

prospects declined as Sam's popularity and success as an author and lecturer

rose. Samuel Clemens would eventually become the main source of financial

support for his older brother.

_____

Mark Twain and "A

Small Piece of Spite" - September 1864

Samuel Clemens left Nevada for California in May 1864 and by

June of that year was working as a reporter for the San Francisco Daily

Morning Call. By September 1864 Clemens had gotten into a war of words

with one of the most prominent undertakers in San Francisco -- Atkins Massey

who buried about 16,000 San Francisco residents during his career. In late

August one of Massey's undertaking staff had played a hoax on the local reporters

by entering a false name in the list of the dead posted outside their office.

A number of newspapers had published the name and were forced to issue a retraction

a couple of days later. Although Clemens was not involved in the false story,

he readily took up the cause on behalf of his fellow reporters after undertaker

Massey refused to allow further access to his records. Not only did Clemens

battle Massey with the printed word, but he worked to insure that Massey would

lose his lucrative arrangement doing business with the city coroner of San

Francisco. On September 24 Clemens wrote to his mother and sister about Massey

and his staff of undertakers:

They refused me & other reporters some information at a branch of the

Coroner's office -- Massey's undertaker establishment, a few weeks ago.

I published the wickedest article on them I ever wrote in my life, &

you can rest assured we got all the information we wanted after that. It

made Mr. Massey come to his milk, mighty quick. Next week the Coroner died,

& when they came to fill his vacancy, I had a candidate pledged to take

the lucrative job out of Massey's hands, & I went into the Board of

Supervisors & button-holed every member & worked like a slave for

my man. When I began he hadn't a friend in the Board. He was elected, just

like a knife, & Mr. Massey is out in the cold. I learned to pull wires

in the Washoe Legislature, & my experience is, that when a bill is to

be put through a body like that, the only thing necessary to insure success

is to get the reporters to log-roll for it (Letters, Vol, 1, p. 312-313).

In his "wicked article" which appeared in the Daily Morning

Call on September 6 under the title "A

Small Piece of Spite" Clemens called the undertaker and his staff

"underlings at the coffin-shop" and "forty-dollar understrappers."

Four days after Twain's "A Small Piece of Spite" appeared, Coroner

Benjamin A. Sheldon, who had a branch office in Massey's undertaking establishment

died. His replacement Dr. Stephen R. Harris who Clemens supported for the

position, ended the arrangement with undertaker Atkins Massey.

_____

Mark Twain and Undertakers in the Californian

and San Francisco Dramatic Chronicle - 1865

Samuel Clemens's biographer Edgar M. Branch noted "undertakers

usually upset him" (Clemens of the Call, p. 235). Branch never

attempted to provide an explanation for the reason behind the source of the

animosity. However, by 1865 Clemens's use of undertaker adjectives, metaphors

and similes in his writings was becoming commonplace. In a July 1, 1865 article

that he wrote for the San Francisco literary weekly Californian titled

"Answers

to Correspondents" he responded to faux questions which he himself

had written. Clemens's question from a "young actor" describes a

young man who has been criticized in the newspaper for "instead of laughing

heartily, as it was my place to do, I smiled as blandly -- and as guardedly,

apparently as an undertaker in the cholera season. These mortuary comparisons

had a very depressing effect upon my spirits ..." Clemens's advice to

the "young actor" was to depend on the audience and not the newspaper

for reliable criticism.

In March 1865 Charles and Michael DeYoung founded the San Francisco

Dramatic Chronicle newspaper. From late October through mid-December 1865

Clemens contributed dozens of brief unsigned articles. Positive identification

of his contributions is not possible. However, based on supporting evidence

related to their content, some articles can be attributed to him with a high

degree of confidence. Clemens engaged in a newspaper feud with rival local

reporter Albert S. Evans of the San Francisco Alta California who wrote

under the pen name Fitz Smythe. Edgar Branch has identified two articles appearing

in the Dramatic Chronicle of November 11 and 13, 1865 which are likely

Clemens's work. Titled "Cheerful Magnificence" (November 11) and

"In Ecstacies" (November 13) the author took to task both Fitz Smythe

and Clemens's old nemesis San Francisco undertaker Atkins Massey.

Daily Dramatic Chronicle, November 11, 1865, p. 3.

Cheerful Magnificence.

Our friend Fitz Smythe of the Alta, goes into

raptures over a certain "magnificent funeral car" recently

received by "Atkins Massey, the well known undertaker."

Fitz Smythe fairly "gloats" over this piece of sepulchral

gorgeousness, summoning his choices rhetoric to the task of describing

its beauties and perfections. He dwells unctuously on its "elegance

of design," its "beauty of finish," its "costly

material and workmanship," which he avers, in an ecstasy of admiration,

quite "excel anything of the kind ever produced in America."

Furthermore, he expresses the opinion that "the term, luxury

of grief, may well be applied to this magnificent establishment."

What delightful enthusiasm, considering the subject! It seems as if

the fascinated youth really hankered after "the luxury"

of being locomoted to Lone Mountain in that "gorgeous establishment."

|

Daily Dramatic Chronicle, November 13, 1865, p. 4.

In Ecstasies.

Fitz Smythe has gone into spasms of delight over a magnificent

hearse (our language is tame, compared to his,) which has just been

imported here by one of our undertakers. This "genius of abnormal

tastes" is generally gloating over a rape, or a case of incest,

or a dismal and mysterious murder, or something of that kind; he is

always going into raptures about something that other people shiver

at. Now, he looks with a lecherous eye on this gorgeous star-spangled

banner bone-wagon, and would become positively frantic with delight

if he could only see it in its highest reach of splendor once with

a five hundred dollar coffinful of decaying mortality in it. He could

not contain his enthusiasm under such thrilling circumstances; he

would swing his hat on the street corners and cheer the funeral procession.

This fellow must be cramped down a little. He would burst with ecstasy

if he cold clasp a real, sure-enough body-snatcher to his bosom once,

and be permitted to make an item of it. He must be gagged. Otherwise

he will seduce some weak patron of the Alta into dying, for

the sake of getting the first ride in the pretty hearse.

|

According to Branch, "Every partisan of Clemens will hope that he wrote

those words, not wanting to deny him the intensest pleasure of having yoked

Massey and Fitz Smythe together for this double decapitation (Clemens of

the Call, p. 235).

Mark Twain and San Francisco's Lone Mountain Cemetery -

February 1866

While in California Sam Clemens continued to write as a correspondent

for the Virginia City Territorial Enterprise sending occasional letters

from San Francisco. In a letter

to the Enterprise dated February 3, 1866 and published a few days

later he took another group of San Francisco undertakers to task. By coincidence,

the San Francisco Lone Mountain cemetery controlled by the undertakers had

the same name as the cemetery where Jennie Clemens was buried in Carson City.

In an article titled "More

Cemeterial Ghastliness" Clemens referred to an earlier article he

had sent the Enterprise. (Unfortunately, a printing of the earlier

article has not been found.) He wrote:

I spoke the other day of some singular proceedings of a firm of undertakers

here, and now I come to converse about one or two more of the undertaker

tribe. I begin to think this sort of people have no bowels -- as the ancients

would say -- no heart, as we would express it. They appear to think only

of business -- business first, last, all the time. They trade in the woes

of men as coolly as other people trade in candles and mackerel. Their hearts

are ironclad, and they seem to have no sympathies in common with their fellow

men.

A prominent firm of undertakers here own largely in Lone Mountain Cemetery

and also in the toll-road leading to it. Now if you or I owned that toll-road

we would be satisfied with the revenue from a long funeral procession and

would "throw in" the corpse -- we would let him pass free of toll

-- we would wink placidly at the gate-keeper and say, "Never mind this

gentleman in the hearse -- this fellow's a dead-head." But the firm

I am speaking of never do that -- if a corpse starts to Paradise or perdition

by their road he has got to pay his toll or else switch off and take some

other route. And it is rare to see the pride this firm take in the popularity

and respectability of their cemetery, and the interest and even enthusiasm

which they display in their business.

He ended the article with a mock conversation with one of the undertakers.

The issue over the exorbitant prices being charged San Francisco residents

for burial in Lone Mountain Cemetery would be debated in city government throughout

1866. However, a few weeks after his article was published in the Enterprise,

Clemens accepted an assignment with the Sacramento

Daily Union and set sail for the Sandwich Islands (Hawaii) on March

7, 1866. Had he remained in San Francisco he, no doubt, would have continued

the battle of words against the proprietors of Lone Mountain Cemetery.

_____

Mark Twain, the Sandwich Islands, and Charles Coffin Harris - 1866-67

Charles Coffin Harris, minister of finance in the Sandwich Islands, was

described by Clemens as having a "cadaverous undertaker's countenance."

Harris, who was never an undertaker but had a middle name that invoked memories

of undertakers, eventually became one of Clemens's most vilified targets.

Samuel Clemens spent about five months in the Sandwich Islands from March

to July 1866. He sent back twenty-five

letters to the Sacramento Daily Union which were reprinted in newspapers

around the country. Of all the people and characters that he met in the Sandwich

Islands, the one he most vilified in print was an American who had the middle

name of "Coffin." Clemens's dislike of Harris was equal to his dislike

of men who were undertakers and he continually described Harris as having

undertaker traits. Harris was a lawyer born in New Hampshire who had gone

to the Sandwich Islands and became a close adviser to King Kamehameha V. Harris

later served as minister of foreign affairs and as a chief justice of the

Hawaiian Supreme Court. One historian has observed that Harris:

. . . deserved something better than the sneering obloquy heaped upon him

by the American humorist [in the Sacramento Daily Union]. It is true

that Harris had an unfortunate domineering manner, an air of superiority

and condescension that infuriated some people and repelled many others;

but he was a man of considerable natural ability, indefatigable industry,

and unimpeachable personal integrity (Mark Twain's Notebooks & Journals,

Vol. 1, p. 119).

Clemens visited the Hawaiian legislature at work in Honolulu in May. In a

letter dated May 23, 1866 and published in the Daily

Union on June

21, 1866, he vilified Harris in a manner reserved for his most hated enemies:

Minister Harris is six feet high, bony and rather slender, middle-aged;

has long, ungainly arms; stands so straight that he leans back a little;

has small side whiskers; from my distance his eyes seemed blue, and his

teeth looked too regular and too white for an honest man; he has a long

head the wrong way - that is, up and down; and a bogus Roman nose and a

great, long, cadaverous undertaker's countenance, displayed upon which his

ghastly attempts at humorous expressions were as shocking as a facetious

leer on the face of a corpse. He is a native of New Hampshire, but is unworthy

of the name of American. I think, from his manner and language to-day, that

he belongs, body and soul, and boots, to the King of the Sandwich Islands

and the "Lord Bishop of Honolulu." He has no command of language

-- or ideas. His oratory is all show and pretense; he makes considerable

noise and a great to do, and impresses his profoundest incoherencies with

an oppressive solemnity and ponderous windmill gesticulations with his flails.

He raises his hand aloft and looks piercingly at the interpreter and launches

out into a sort of prodigious declamation, thunders upward higher and higher

toward his climax --words, words, awful four-syllable words, given with

a convincing emphasis that almost inspires them with meaning, and just as

you take a sustaining breath and "stand by" for the crash, his

poor little rocket fizzes faintly in the zenith and goes out ignominiously.

The sensation one experiences is the same a miner feels when he puts in

a blast which he thinks will send the whole top of a mountain to the moon,

and after running a quarter of a mile in ten seconds to get out of the way,

is disgusted to hear it make a trifling, dull report, discharge a pipe-full

of smoke, and barely jolt half a bushel of dirt. After one of these incomprehensible

ravings, Mr. Harris bends down and smiles a horrid smile of self-complacency

in the face of the Minister of the Interior -- bends to the other side and

continues it in the face of the Minister of Foreign Affairs; beams it serenely

upon the admiring lobby, and finally confers the remnants of it upon the

unhappy interpreter -- all of which pantomime says as plainly as words could

say it: "Eh? -- but wasn't it an awful shot?" Harris says the

weakest and most insipid things, and then tries by the expression of his

countenance to swindle you into the conviction that they are the most blighting

sarcasms. And in seven years I have never lost my cheerfulness and wanted

to lay me down in some secluded spot and die, and be at rest, until I heard

him try to be funny to-day. If I had had a double-barreled shotgun I would

have blown him into a million fragments.

Clemens resumed his attack on Harris a month later after catching a glimpse

of him at a funeral for a Hawaiian princess. In a letter published July

30, 1866 in the Daily Union he wrote:

Harris was an American once (he was born in Portsmouth, N.

H.), but he is no longer one. He is hoopilimeaai to the King. How do you like

that, Mr. H.? How do you like being attacked in your own native tongue?

[NOTE TO THE READER. - That long native word means -- well, it means Uriah

Heep boiled down -- it means the soul and spirit of obsequiousness. No genuine

American can be other than obedient and respectful toward the Government

he lives under and the flag that protects him, but no such an American can

ever be hoopilimeaai to anybody.]

Clemens returned to San Francisco in late August 1866 while his news reports

from the Sandwich Islands were still appearing in the Sacrament Daily Union.

A notebook entry written shortly after his return refers to Harris as "that

---cking Harris" (Notebooks and Journals, Vol. 1, p. 149).

On October 2 Clemens embarked on a lecture tour around the state of California

which eventually spread to the east coast. The topic of his presentation was

usually announced as "Our Fellow Savages of the Sandwich Islands."

The surviving fragments of Clemens's original notes for his speech indicate

that Harris was a butt of his jokes in that lecture (Letters, Vol. 5,

p. 331). When Clemens lectured in Quincy, Illinois on April 9, 1867, his old

colleague from Nevada Major Dallam, who later committed suicide in the spring

of 1868 with an overdose of laudanum, wrote of Mark Twain's upcoming appearance

in the Quincy Whig. He made no mention of their previous feud that

had occurred shortly after Jennie Clemens's death:

We had a call, yesterday, from an old friend, Mark Twain (Sam

Clemens, Esq.), the California humorist whom we had not seen since we parted

from him on the sunward side of the Sierra Nevadas some three years ago. The

aroma of sage brush does not hang around him still. The gentle "Washoe

Zephyrs," which lifted a loaded quartz wagon with remarkable ease, have

left no rough traces upon his good-humored face. The many feet which he once

owned in Washoe, "wild cat" claims, out of which he expected to

realize untold wealth, have long since been "sold for assessments,"

and yet he can still laugh, and make others laugh. He is, indeed, "a

fellow of infinite jest" -- as our friends may learn to their entire

satisfaction by attending a lecture which he proposes to give in this city

on Tuesday next.

Mark's funny stories and quaint sayings are not so well known here as in

California, where they have secured for him a reputation not surpassed by

any humorist that ever attempted to amuse that people, who are, perhaps,

more critical than any other community in the Union.

His wit and his style are peculiarly his own -- original, racy and irresistible.

The first time we heard Mark was at Carson City, the capital of the State

of Nevada, on the assembling of the Territorial Legislature in the winter

of 1863-4. Hon. James W. Nye (now U.S. Senator) was then Governor of the

Territory. After the delivery of the inaugural to the "assembled wisdom"

of Silverland, Mark Twain took the speaker's stand and delivered his inaugural

as Governor of the Territory chosen by the "Third House," to a

very large audience of gentlemen and about all the ladies then in Carson

City. It was received with great applause and roars of laughter. Mark gave

the Governor some hard hits, in a sly way, but no one enjoyed the fun more

than rotund and rubicund Nye.

The lovers of genial humor will find nothing coarse or vulgar in Mark Twain's

lecture. He also sometimes (by mistake, he says) indulges in beautiful flights

of fancy and eloquence. But of his talent as a lecturer, our citizens will

soon have an opportunity of judging, and we bespeak for him, in advance,

a fair audience (online

at "Mark Twain in His Times").

Clemens extended his lecture tour on the Sandwich Islands into May 1867,

ending at Irving Hall in New York City on May 15. He was in Washington, D.C.

and corresponding with the San Francisco Alta California when he again

encountered Charles Coffin Harris. In a letter from Washington dated May 26,

1867 and published in the Alta

on July 21, 1867 he alerted his readers to the fact that:

His Excellency C. C. Harris, of Honolulu -- is to visit Washington

as a sort of Envoy Extraordinary to engineer a Reciprocity treaty between

the Hawaiian Government and ours. I have got to call on Harris. I owe it to

my country to do it. I must conjure Harris by the new dignity that has been

conferred upon him of the Grand Cross of the Legion of something or other;

and by this other dignity of being by far the most extraordinary Envoy Extraordinary

that ever was created by any Government history hath mentioned; and by the

love and the respect he once bore this land of his nativity before he was

born again as a royalty-worshipping Kanaka, not to lay his unsanctified hand

upon anything here that he can't carry. It is his unhappy instinct to gobble,

gobble, gobble -- gobble up and carry off. Whether it be to gouge native (chiefs,

or seek distinction on high as an Elder in Bishop Staley's Church and pass

around the hat, (oh, blind and deluded congregation that would trust him with

it ) or grab all the heavy offices, from Minister of Finance down to Attorney-General-by-brevet,

and try to run the whole Hawaiian Government by himself, his instinct is the

same, and it is always to gobble. So I must warn him.

And he must not swell around Washington and make eloquent speeches that

seem to be splendid flights of oratory, but won't stand a fire-assay for

sense, and won't wash for coherence, either, because we have got people

in Congress who are just as good as he is at that, and so he won't attract

any attention.

I must tell him to mind his own business -- to mind his reciprocity treaty,

and keep his hands off the things. If he does his work just exactly as he

wants to do it, and as only his tireless industry and his marvellous cheek

can do it, he can succeed in clinching a treaty that will make American

interests very sick in the Sandwich Islands. The Herald's Honolulu

correspondence of this morning rather warns Congress to look out for Harris,

and I am inclined to think the warning was very well put in, and would find

an echo from every American in the Islands. I still continue in my set opinion

that Harris won't do.

Shortly after his latest attack on Harris, Clemens landed another assignment

for the Alta -- one that would take him abroad.

_____

Mark Twain Tours the Holy Land - 1867

Working as a correspondent for the San Francisco Alta California,

Clemens set sail aboard the Quaker City for a tour of Europe and the

Holy Land in June 1867. The tour extended into November 1867 and he sent fifty

travel letters back to the Alta which were reprinted in newspapers

across the United States. The letters would eventually become the backbone

of his first best seller The Innocents Abroad which would launch his

career as a nationally known author.

Clemens could not long shake his memories of and resentment of undertakers

and when the opportunity arose to lampoon them in print, he did not fail to

do so. Writing from Genoa, Italy on July 16, 1867 he related his impressions

of seedy Italians who followed his group of tourists waiting for them to throw

away their cigar stubs:

You cannot throw an old cigar "stub" down anywhere, but some

seedy rascal will pounce upon it on the instant. I like to smoke a good

deal, but it wounds my sensibilities to see one of these stub-hunters watching

me out of the corners of his hungry eyes and calculating how long my cigar

is going to last. It reminded me, too, painfully of that San Francisco undertaker

who used to go to sick-beds with his watch in his hand and time the corpse

(McKeithan, p. 43).

Following his description of the cigar stub hunters, he began a description

of the palaces of Genoa his group toured and again the image of the undertaker

was invoked:

We have visited several of the palaces -- immense thick-walled piles, with

great stone staircases ... and portraits of heads of the family, in plumed

helmets and gallant coats of mail, and patrician ladies, in stunning costumes

of centuries ago. ... and so all the grand empty saloons, with their resounding

pavements, their grim pictures of dead ancestors, and tattered banners with

the dust of bygone centuries upon them, seemed to brood solemnly of death

and the grave, and our spirits ebbed away, and our cheerfulness passed from

us. ... There was always an undertaker-looking villain of a servant along,

too, who handed us a programme, pointed to the picture that began the list

of the saloon he was in, and then stood stiff and stark and unsmiling in

his petrified livery till we were ready to move on to the next chamber,

and then he marched sadly ahead and took up another malignantly respectful

position as before. I took up so much time praying that the roof would fall

in on these dispiriting flunkeys that I never had any left to bestow upon

palace and pictures (McKeithan, pp. 43-4.)

Clemens would later slightly revise and use the two passages in Chapter 27

of The Innocents Abroad. The illustrator for the first edition of the

book chose to draw the "undertaker-looking" servant for the passage

describing Genoa palaces.

Illustration

from first edition of

THE INNOCENTS ABROAD labeled"Petrified

Lackey."

However the word "lackey" was never used in Twain's actual text.

The tour of the Holy Land ended in November 1867 and Clemens

returned to Washington, D.C. where he continued to contribute letters to the

Alta California.

_____

Mark Twain Encounters Charles Coffin Harris Again

Harris is here yet. Harris is Lord High Minister of Finance to the King

of the Sandwich Islands when he is at home and it don't rain. But he is

"His Royal Hawaiian Majesty's Envoy to the United States" now,

and no man is sorrier than I am that his wages are stopped for the present.

I met him and conversed with him at the house of a mutual friend a night

or two ago, and that is how I happen to know how to spell his title all

the way through without breaking my neck over any of the corduroy syllables.

I never saw Harris so pleasant and companionable before. He is really

very passable company, until he tries to be funny, and then Harris is

ghastly. He smiles as if he had his foot in a steel trap and did not want

anybody to know it. I can forgive that person anything but his jokes --

but those, never. While Harris continues to joke there will be a malignant

animosity between us that no power can mollify.

Harris' business here is to get our Government to remove our man-of-war

from the Sandwich Island waters. To give this enterprising devil his due,

he has done everything he possibly could do to accomplish his mission,

and it was ungraceful in the King to stop his salary. He could not accomplish

it and I suppose nobody could. It is a good place out there for a man-of-war;

she is not doing any harm; she is not going to do any harm; and until

a fair, reasonable reason is given for banishing her, she will remain.

In placing her there, no offence whatever was meant to the King or the

country, any more than we mean to offend the Sultan when we anchor a frigate

in the harbor of Smyrna.

I have missed Harris during the last day or two. I wonder what is become

of him. I grieve to see a man fail in an honest endeavor; and now that

his King has turned against him, I even wish that Harris could succeed

in his mission.

This softening attitude toward Harris was short-lived. Several

years later he would again vilify him in print.

While working as a reporter in Washington, D.C. in 1868, Clemens also contributed

six letters to the Chicago Republican. In two of the letters written

in February 1868 he again invoked the image of undertakers into his descriptions.

It had been four years to the month since Jennie Clemens had died back in

Carson City, Nevada.

Writing from Washington on Valentine's Day in a letter

published on February 19 in the Republican, Clemens humorously

described Valentines he received:

I usually receive notes with pictures in them; pictures of deformed shoemakers;

pictures of distorted blacksmiths; pictures of cadaverous undertakers; pictures

of reporters taking items at a fire and stealing clothes; and oftenest,

pictures of asses, with ears longer than necessary, writing letters to newspapers.

I refer to the reception given by the "Illinois State Association,"

yesterday evening. Or, rather, it was more a "reunion," with considerable

"at home" in it than the funereal high comedy they call a "reception

in Washington." ...

I only met one icicle in the whole party. He shook hands without cordiality,

and bowed with altogether too much condescension. I said, with a vivacity

that considerably oversized the importance of the remark:

"It has been a very fine day, sir."

Then this monument, this undertaker, this galvanized graveyard said:

"Sir, what the weather may be, or what the weather may not be, concerns

not me, when my country is in danger." ...

I think this old sepulchre was a member of Congress, but I did not catch

his name distinctly. But why do such people go to social gatherings, and

practice their execrable speeches on unoffending strangers? Why do they

go around saving the country all the time, and snubbing the weather? Why

do not they do like Garret Davis, and persecute Congress, which is paid

to be persecuted? These harmless lunatics only distress the guests at an

evening party, without absolutely scaring them. I would be ashamed to act

so poor a part as that. If I had to be a lunatic, I do think I would have

self-respect enough to be a dangerous one. I hate that solemn-visaged body-snatcher

now, and if he is a Congressman I shall always try to find out all the mean

things I can that other people do, and put them in print and attribute them

to him. I think that will make him wince.

One of the ultimate insults Clemens was incorporating was the description

of someone as an "undertaker" or "body-snatcher."

_____

The Buffalo Express - 1869-70

In January 1868 Elisha Bliss of the American Publishing Company made arrangements

with Clemens to publish a book based on the Quaker City excursion through

Europe and the Holy Land. Clemens

worked on his manuscript for a few months while living in Washington.

In March 1868 he left Washington to return to San Francisco to obtain from

the Alta California the rights to reuse his Alta newspaper travel

letters describing the trip. Clemens completed his manuscript in June 1868

and several months later turned his attention to correcting proofs of the

book with his new wife-to-be Olivia "Livy" Langdon of Elmira, New

York, a sister of one of his Quaker City traveling companions. The

Innocents Abroad was published in July 1869 and widely praised by critics.

In August 1869 Clemens purchased one-third interest in the Buffalo

(New York) Express newspaper with money borrowed from Livy's father

Jervis Langdon. Clemens wrote numerous essays and editorials for the Express.

On of his earliest contributions was "A Day at Niagara" published

in the Express on August 21, 1869. This humorous and satiric sketch

of a visit to Niagara Falls concludes with Mark Twain getting tossed in the

Falls. A greedy coroner sitting on the bank declines to rescue him.

| The sketch retitled "A Visit to Niagara" was included in the

collection Sketches New and Old published in 1875 and featured

an illustration of the undertaker sitting on the bank waiting for Mark

Twain to drown. |

Illustration

from first edition of SKETCHES NEW AND OLD |

On September 4, 1869 Clemens published "Journalism in Tennessee"

in the Express. This humorous parody of frontier journalism features

subjects of news reports settling their complaints with the editor with weapons.

One such complainant, Colonel Blatherskite Tecumseh, who is mortally wounded

after a shoot-out remarks with fine humor, "that he would have to say

good morning now, as he had business up town. He then inquired the way to

the undertaker's and left" (Sketches New and Old, p. 47). Although

the sketch is set in Tennessee, Clemens was drawing on his own experiences

from his newspaper days in Virginia City.

On January 22, 1870 Clemens contributed an essay for the Express on

desperadoes, killers and outlaws of Nevada and California and how one in particular,

Jack Williams, contributed to the welfare of the local undertaker.

He killed a good many men. He was a kind-hearted man, and gave all his

custom to a poor undertaker who was trying to get along. But by and bye

some body poked a double barrelled shot gun through a crack while Williams

was sitting at breakfast, and riddled him at such a rate that there was

hardly enough of him left to hold an inquest on -- and then the poor unfortunate

undertaker's best friend was gone, and he had to take in his sign. Thus

he was stricken in the midst of his prosperity and his happiness -- for

he was just on the point of getting married when Jack Williams was taken

away from him, and of course he had to give it up then (Mark Twain at

the Buffalo Express, p. 143).

Clemens once again emphasizes the prosperity undertakers enjoy at the hands

of tragedy.

According to Thomas J. Reigstad in his Scribblin' for Livin' (2013),

Mark Twain published numerous commentary in the pages of the Buffalo Express:

. . .singling out the avarice of coroners who constantly drummed

up business. One of Twain's favorite targets in the Express was Dr.

John J. Burke, a coroner in Buffalo. Twain's mock feud with Burke was particularly

intense in the spring of 1870 when Twain referred to Burke as "our pompous

and officious coroner" and complained about Burke's "personal abuse

of the City Editor of the Express" (City and Vicinity, BME, May

3, 1870). In the April 30 Express, Twain took aim at his greed: "The

zeal of Dr. Burke outruns his wit." And in March, Twain also criticized

the coroner profession in the Express (City and Vicinity, March 23,

1870). (Scribblin' for a Livin', p. 294).

The

Galaxy - 1870

After a long courtship and year-long engagement Samuel Clemens and Olivia

Langdon were married February 2, 1870 and settled in Buffalo. His new book,

The Innocents Abroad, proved to be a success and he received an invitation

to write for the monthly magazine The Galaxy. Clemens had previously

published two articles in The Galaxy in February and May 1868 at the

time he was living in Washington, D. C. Under his new arrangement, Clemens's

first contribution appeared in The Galaxy in May 1870 under the heading

"Mark Twain's Memorandum."

The year 1870 proved to be a year of deaths for the newly married couple.

In the spring Livy's father's health began a rapid decline as he battled stomach

cancer. Jervis Langdon died on August 6, 1870. The following month Livy's

friend Emma Nye died in their Buffalo home of typhoid fever. Livy, suffering

from stress over the loss of both her father and her girl friend delivered

the couple's first child, a son, prematurely. For a while both Livy and her

newborn were extremely ill. With death hovering over the Clemens household,

it is not surprising to find Mark Twain's contributions to The Galaxy

containing references to undertakers.

In the June

1870 Galaxy a short untitled item discussed a Civil War widow's

surprise at the high cost of having her husband embalmed. Written in a humorous,

dark comedy tone, the widow expects an embalming to cost a few dollars and

is surprised to see the charge of seventy-five. The sketch was later reprinted

in Sketches New and Old in 1875 under the title "The Widow's Protest."

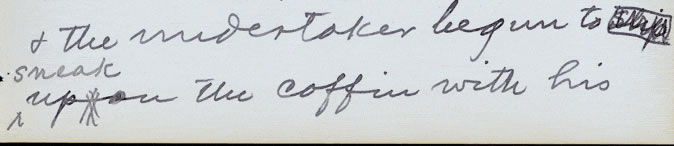

In the November

1870 Galaxy, a few months after Jervis Langdon's death, Clemens

published an item titled "A Reminiscence of the Back Settlements."

The sketch features a mock monologue by an undertaker who is chatty and cheerful

regarding the wishes of his most recent customer. The sketch concludes with

the statement, "a healthy and wholesome cheerfulness is not necessarily

impossible to any occupation. The lesson is likely to be lasting, for it will

take many months to obliterate the memory of the remarks and circumstances

that impressed it." This sketch was also reprinted in Sketches New

and Old in 1875 and retitled "The Undertaker's Chat."

The December

1870 Galaxy featured Twain's sketch "Running for Governor"

and included a number of insults Mark Twain received when he imagined himself

running for governor of the state of New York. Among these was "Twain,

the Body-Snatcher."

On December 20, 1870 Clemens replied to a letter from Albert Francis Judd

from the Sandwich Islands. Judd was a Hawaiian missionary and statesman who

later became attorney general of the islands. Judd's letter brought to Clemens's

mind memories of Charles Coffin Harris. Clemens replied to Judd who had recently

traveled to the United States:

I do wish you had spent a day or two with us in Buffalo, & I

beg that you will when you come again. I love to see people from

the Islands notwithstanding I conducted myself so badly there & left

behind me so unenviable a name. But then you know they honor Harris there,

& so while that continues the preferable distinction is to stand dishonored,

maybe. I never stole anything in the Islands -- and ah, me, I wish Harris

could say as much! (Letters, Vol. 4, p. 278).

There is no historical evidence to suggest Charles Coffin Harris ever stole

from the people of Hawaii or was dishonest.

_____

Roughing It - 1871-72

Following the success of his book The Innocents Abroad,

Clemens turned his attention almost immediately to another book. Initially

he considered writing about his trip to the Sandwich Islands and later decided

to expand the focus to include his time in Nevada and the west. In March 1870

he asked Orion to send his journal from their stagecoach journey to Nevada

as well as other newspaper clippings and scrapbook items. Clemens negotiated

another contract with Elisha Bliss of American Publishing Company in July

1870 for the book that would eventually be titled Roughing It. Clemens's

intent was to have the manuscript finished by the end of 1870. However, the

death of Jervis Langdon in August, the death of Emma Nye in September, Livy's

difficulty with the birth of their first child, and writing commitments for

the Buffalo Express and Galaxy hindered his ability to concentrate

on writing his book manuscript. He was unable to submit any manuscript until

March 1871. That same month Clemens decided to terminate his association with

both the Buffalo Express and The Galaxy in order to focus on

his career as a writer of books.

Mark

Twain's last "Memoranda" for The Galaxy appeared in April

1871. In it he told his readers:

I have written for The Galaxy a year. For the last eight months,

with hardly an interval, I have had for my fellows and comrades, night and

day, doctors and watchers of the sick! During these eight months death has

taken two members of my home circle and malignantly threatened two others.

All this I have experienced, yet all the time been under contract to furnish

"humorous" matter once a month for this magazine. I am speaking

the exact truth in the above details. Please to put yourself in my place

and contemplate the grisly grotesqueness of the situation. I think that

some of the "humor" I have written during this period could have

been injected into a funeral sermon without disturbing the solemnity of

the occasion.

The Clemenses relocated to Livy's hometown of Elmira, New York where he was

able to complete his manuscript for Roughing It in August. In October

1871 the couple moved to Hartford, Connecticut -- the hometown of American

Publishing Company. In mid-October 1871 Clemens launched another

lecture tour through the Northwest and Midwest that would extend into February

1872. In December he started incorporating excerpts from his upcoming

book in his lectures. His lecture tour provided needed income as well as advance

publicity for his new book.

Roughing It was officially released in the United States on February

19, 1872. The book is not pure autobiography nor a travel volume. Clemens

took many liberties with the truth, invented episodes, embellished events

and omitted many important events in his life while in Nevada. Missing entirely

from the book is any mention of the death of Jennie Clemens. However, the

topics of funerals and undertakers were included. He introduced chapter 47

of his book with the passage:

Somebody has said that in order to know a community, one must observe the

style of its funerals and know what manner of men they bury with most ceremony.

I cannot say which class we buried with most eclat in our "flush times,"

the distinguished public benefactor or the distinguished rough -- possibly

the two chief grades or grand divisions of society honored their illustrious

dead about equally; and hence, no doubt, the philosopher I have quoted from

would have needed to see two representative funerals in Virginia before

forming his estimate of the people (Roughing It, p. 308).

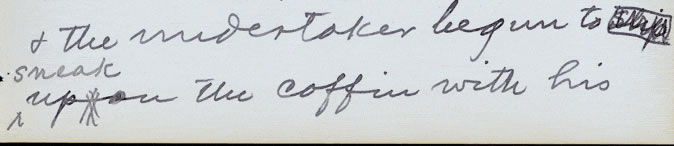

Chapter 47 continues in a comic vein emphasizing the communication difficulties

that occur when Scotty Briggs, a Virginia City "stalwart rough"

tries to arrange a funeral with a new minister described as a "fledgling

from an eastern theological seminary." Both characters have difficulty

understanding the jargon and slang of the other.

Chapter 53 of Roughing It, features "The Story of the Old Ram"

-- a story Clemens also used in his public lectures -- a story about an old

miner named Jim Blaine who begins a tale about his grandfather's old ram but

never reaches a conclusion because he continually gets sidetracked onto other

topics. Among the other topics is a story of a vulture-like undertaker:

Miss Jacops was the coffin-peddler's wife - a ratty old buzzard, he was,

that used to go roosting around where people was sick, waiting for 'em;

and there that old rip would sit all day, in the shade, on a coffin that

he judged would fit the can'idate; and if it was a slow customer and kind

of uncertain, he'd fetch his rations and a blanket along and sleep in the

coffin nights (Roughing It, p. 364).

Illustration

of an undertaker from first edition of ROUGHING IT.

Langdon Clemens, Samuel and Livy's first born child died June

2, 1872 in Hartford, just a few months after Roughing It was published.

On June 18 Clemens sent a letter to Louise Chandler Moulton who had written

a positive review of Roughing It for the New York Tribune on

June 10. He also thanked her for an expression of sympathy over his son's

death:

We did feel such a jubilant pride in our boy. You know how honest is the

conviction that the child that is gone was the one only spirit that was

perfect. When we shall feel "reconciled," God only can tell. To

us it seems a far away time, indeed (Letters, Volume 5, pp. 108-09).

Sharing in the family's grief were Orion and Mollie Clemens

who came to visit and comfort the family in the days after Langdon's death.

_____

Charles Coffin Harris, Again - 1873

On December 28, 1872 Whitelaw Reid, editor and proprietor of

the New York Tribune, invited Clemens to contribute a few articles

to his newspaper on any topic of interest with a promise to pay enough to

make it worth his while. The death of Hawaiian King Kamehameha V had recently

been announced in the New York newspapers and his obituary had been published

in the Tribune on January 2, 1873. Clemens sent the Tribune

two articles on the Sandwich Islands he wrote on January 3 and January 6,

1873. In the second article which was published in the Tribune on January

9, 1873 Clemens again took up his vendetta against Charles Coffin Harris and

among the many faults he gave to Harris was again his undertaker countenance:

The "Royal Ministers" are natural curiosities. They are white

men of various nationalities, who have wandered thither in times gone by.

I will give you a specimen -- but not the most favorable. Harris, for instance.

Harris is an American -- a long-legged, vain, light-weight village lawyer

from New-Hampshire. If he had brains in proportion to his legs, he would

make Solomon seem a failure; if his modesty equaled his ignorance, he would

make a violet seem stuck-up; if his learning equaled his vanity, he would

make Avon Humboldt seem as unlettered as the backside of a tombstone; if

his statue were proportioned to his conscience, he would be a gem for the

microscope; if his ideas were as large as his words, it would take a man

three months to walk around one of them; if an audience were to contract

to listen as long as he would talk, that audience would die of old age;

& if he were to talk until he said something, he would still be on his

hind legs when the last trump sounded. And he would have cheek enough to

wait till the disturbance was over, & go on again.

Such is (or was) His Excellency Mr. Harris, his late Majesty's Minister

of This, That, & The Other -- for he was a little of everything; &

particularly & always he was the King's most obedient humble servant

& loving worshiper, & his chief champion & mouthpiece in the

parliamentary branch of ministers. And when a question came up (it did n't

make any difference what it was), how he would rise up & saw the air

with his bony flails, & storm & cavort & hurl sounding emptiness

which he thought was eloquence, & discharge bile which he fancied was

satire, & issue dreary rubbish which he took for humor, & accompany

it with contortions of his undertaker countenance which he believed to be

comic expression!

He began in the islands as a little, obscure lawyer, & rose (?) to

be such a many-sided official grandee t hat sarcastic folk dubbed him, "the

wheels of the Government." He became a great man in a pigmy land --

he was of the caliber that other countries construct constables & coroners

of. I do not wish to seem prejudiced against Harris, & I hope that nothing

I have said will convey such an impression I must be an honest historian,

& to do this in the present case I have to reveal the fact that this

stately figure, which looks so like a Washington monument in the distance,

is nothing but a thirty-dollar windmill when you get close to him.

Harris loves to proclaim that he is no longer an American, & is proud

of it; that he is a Hawaiian through & through, & is proud of that

too; & that he is a willing subject & servant of his lord &

master, the King, & is proud & grateful that it is so (Letters,

Volume 5, pp. 570-71).

Shortly after writing his Tribune contributions, Clemens

took up another project -- his first novel.

_____

The Gilded Age: A Tale of To-Day - 1873

Clemens's first novel The Gilded Age was written in collaboration

with his Hartford neighbor Charles Dudley Warner, editor of the Hartford Courant

newspaper. The idea of writing a novel together originated around the dinner

table in early 1873 when Livy Clemens and Mrs. Warner challenged their husbands

to write "better" novel than the ones they had been recently criticizing.

Clemens and Warner accepted their wives' challenge and completed the project

in April 1873. Most of the chapters were written by primarily either Clemens

or Warner, but both contributed ideas and suggestions to almost every chapter

as they shared their work. The final result was a novel that satirized America's

obsession with the pursuit of wealth and skewered big business and politics.

Chapter 43 of The Gilded Age features the character Philip

Sterling, a bright and honest Yale graduate experiencing Washington, D.C.:

There was a little newspaper editor from Phil's native town, the assistant

on a Peddletonian weekly, who made his little annual joke about the "first

egg laid on our table," and who was the menial of every tradesman in

the village and under bonds to him for frequent "puffs," except

the undertaker, about whose employment he was recklessly facetious. In Washington

he was an important man, correspondent, and clerk of two house committees,

a "worker" in politics, and a confident critic of every woman

and every man in Washington. He would be a consul, no doubt, by and by,

at some foreign port, of the language of which he was ignorant; though if

ignorance of language were a qualification he might have been a consul at

home. His easy familiarity with great men was beautiful to see, and when

Philip learned what a tremendous underground influence this little ignoramus

had, he no longer wondered at the queer appointments and the queerer legislation

(The Gilded Age, p. 398-99).

Scholars believe that Warner wrote most of Chapter 43. However,

the reference in the above paragraph to a small town newspaper editor who is

obligated to "puff" all the trademen except the undertaker about whom

he could be "recklessly facetious" is reminiscent of Clemens's experiences

in Carson City and California. The criticism of that same editor as ignorant

enough to be a consul is also similar in tone to Clemens's Tribune letters

stating that Hawaiian Minister Charles Coffin Harris was "of the caliber

that other countries construct constables & coroners." In all likelihood,

this particular paragraph benefited in part, if not in total, from Clemens's

input.

_____

King David Kalakaua Defends Harris and Attempts to Explain

Mark Twain - 1874

King David

Kalakaua of Hawaii governed from 1874 - 1891.

Photo from the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Hawaiian King Kamehameha V was succeeded by William Lunalilo

in 1873 who held office for shortly over a year before his death in February

1874. David Kalakaua succeeded William Lunalilo King David Kalakaua appointed

Charles Coffin Harris as First Associate Justice of the Hawaiian courts and

later promoted him to Chief Justice and Chancellor -- a testament to the high

regard Harris held with the ruling dynasty of Hawaii in spite of Clemens's

attempts to ridicule him. It was a position Harris would hold until his death

in 1881.

Samuel Clemens first met David Kalakaua in the Sandwich Islands

in April 1866 when Kalakaua was serving as Grand Chamberlain under King Kamehameha

V. Shortly after meeting him, Clemens described him in a letter to his mother

and sister, "although darker than a mulatto, he has an excellent English

education & in manners is an accomplished gentleman" (Letters,

Volume 1, p. 394).

After Kalakaua succeeded to the Hawaiian throne in February

1874 he made a tour of the United States in the fall of that year accompanied

by all the publicity usually given to royal dignitaries. Kalakaua visited

in New York in late December 1874. Clemens was in New York on December 23

for the 100th

performance of "The Gilded Age," a play based on a book of the

same title he had written with Charles Dudley Warner. Clemens visited with

Kalakaua at the Windsor Hotel in New York on Christmas Eve 1874. That same

day the New York Tribune published an interview with Kalakaua "The

King's Impressions of America" on the front page of the paper. Kalakaua

responded to a question asking his opinion of Mark Twain's portrayal of the

islands:

The King was asked whether the pen-portrait of Minister Harris, a member

of the Cabinet of a former King, was true to life. The King laughed, and

replied that Mr. Harris was a tall, angular, rather awkward, but good-hearted,

well-meaning man. He knew of no personal feeling between Mark Twain and

Mr. Harris, and judged it was the humorist's love of burlesque which had

led him to seize upon the figure of Mr. Harris as a good subject for sport

(Letters, Volume 6, p. 331).

Kalakaua attended a performance of "The Gilded Age" a few days

later. Although Clemens was not in attendance, he issued an invitation for

the King to visit him in Hartford on New Year's Eve. However, other engagements

prevented the King's visit to Hartford. And no further articles deriding Charles

Coffin Harris appeared over Mark Twain's signature.

A Story Mark Twain Never Published: "The Undertaker's Tale"

- 1877