The pictures of Frances Lloyd Paxton, the Countess Massiglia, are small and difficult to see in the photo album that belonged to Mark Twain's daughter Jean Clemens. Jean wrote, "A frame containing six pictures of the Countess Massiglia, hanging in the nurse's room, later Father's." Clemens later inserted the word "infernal" just before the words "Countess Massiglia."

Page from Jean

Clemens's photo album is from the Kevin Mac Donnell collection.

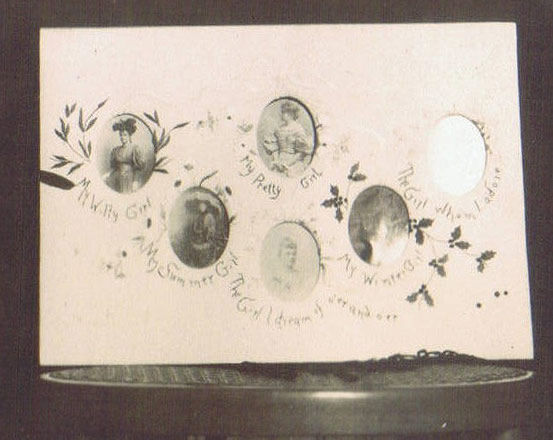

An enlarged

detail of the page from Jean Clemens's photo album courtesy of Kevin Mac Donnell.

The captions surrounding the photos of the countess appear to have been written by an ardent admirer, perhaps her husband, the distinguished Italian diplomat Count Annibale Raybaudi Massiglia. They read: "My Witty Girl," "My Summer Girl," "My Pretty Girl," The Girl I dream of," "My Winter Girl," and "The Girl Whom I adore" -- a photo which had been removed at the time Jean Clemens snapped the picture.

FRANCES LLOYD PAXTON

Frances Lloyd Paxton, later known as the Countess Massiglia, was born January 26, 1861 in Rupert, Pennsylvania. An old passport description states she was 5'3"; had a medium forehead, oval face, grey eyes, straight nose, light brown hair and a fair complexion (1). Census records indicate her father was Benjamin Frank Paxton, born in Pennsylvania in 1836. Her mother was Susan McIlvain Lloyd born in Pennsylvania in 1838. The 1870 census shows the Paxton family living in Philadelphia County near Bridesburg, Pennsylvania. Frank Paxton's occupation is listed as a coal dealer whose personal estate was valued at $9,000. The sum would indicate the family lifted comfortably although they were not extremely wealthy. The family had one live-in servant. Frances's name is listed in the census as "Fannie." Ten years later, the 1880 census shows the Paxton family living in Philadelphia. Ben Paxton's occupation is listed as a lumber dealer. The family had two live in servants. "Fannie" was listed as a student.

In the mid 1880s Frances Paxton married Barnabe Campau. The couple had no children

when their marriage later ended in divorce.

COUNT ANNIBALE RAYBAUDI MASSIGLIA

Count Massiglia was born in Turin, Italy in 1853. He graduated from the University of Genoa in 1875 with a degree in jurisprudence and then began a consular career (2). Massiglia arrived in Philadelphia in October 1889 along with his wife Jeanne. The Philadelphia Inquirer of Oct. 16, 1889 reported, "The new Consul has a dark complexion with a full, red beard and whiskers and dark hair. He is tall and has a well-proportioned figure" (3). Prior to his arrival in Philadelphia, Massiglia had served as an Italian diplomat in Russia, Algeria, Tunisia, Damascus, Beirut, Buenos Aires and Johannesburg.

On April 22, 1891 the Philadelphia Inquirer reported the

death of Jeanne Guillaumet Massiglia, wife of Annibale Raybaudi Massiglia. How

Count Massiglia met Frances Lloyd Paxton Campau is unknown. However, by November

1895 Paxton and Campau were divorced and Paxton married Count Massiglia and

acquired the title of Countess. After his marriage to Paxton, Massiglia was

transferred to Guatemala and thereafter served diplomatic missions to Calcutta

and Bangkok.

MARK TWAIN'S LANDLADY: COUNTESS MASSIGLIA

On October 24, 1903 Samuel Clemens along with his wife Olivia, daughters Clara and Jean, maid Katy Leary, and a nurse departed New York aboard the steamship Princess Irene bound for Italy. The Clemens's secretary Isabel Lyon and her mother would soon follow on the steamer Lahn. Olivia Clemens was in failing health and American doctors thought the mild climate of Italy would benefit her. Clemens made arrangements through George Gregory Smith to rent Villa Reale di Quarto near Florence from Countess Massiglia. Villa di Quarto was a palace built by Cosimo I four hundred years earlier and had gone through the hands of royal families of Würtemberg and Russia. Smith promised Clemens, "I know of no place in Florence where you can be so thoroughly comfortable as at Quarto" (4). Smith's prediction could not have been further from reality. The rental brought Clemens into collision with a woman he would come to detest.

Villa di Quarto

which was owned by Countess Massiglia

On November 3, 1903 the Italian Gazette reported the Clemens family

had hired the Villa Reale di Quarto and remarked "Since buying the Villa

di Quarto the Countess has lavished both money and faultless taste in refitting

and furnishing" (5). However, trouble began

brewing before the first day of the rental agreement. Countess Massiglia refused

to allow the Clemens's servants early entry and access to the home and they

were unable to prepare it for occupation until after the lease took effect.

The Clemens family remained in a hotel nearby until November 9, 1903. Other

disagreements arose when Clemens discovered that the bedroom selected for Mrs.

Clemens could not be used by her because the rental contract expressly forbade

the occupation of that bedroom by any sick person.

ISABEL LYON REMEMBERS FRANCES PAXTON FROM PHILADELPHIA

Isabel Lyon, Clemens's secretary had once lived and worked in Philadelphia as a governess. She remembered Frances Paxton when she was married to Barnabe Campau. She wrote in her diary, "The Countess is none other than a vicious woman of whom I knew a little in Philadelphia about 15 years ago." According to Lyon, Paxton had been divorced from Campau when she was found "tampering with the affections of her mother's boarder." Lyon further commented:

Count Massiglia is far away serving his country as Consul in Persia or Siam, and he is likely to stay there too; and it seems to me that for the sake of peace or freedom, he has left this Villa in the hands of the Countess … Here she remains, a menace to the peace of the Clemens household, with her painted hair, her great coarse voice, her slitlike vicious eyes, her dirty clothes, and her terrible manners. … Her viciousness seems to grow, as she realizes that she cannot make a tool of Mr. Clemens, nor use the lovely Clemens daughters as tools of another kind to give a place in society (6).

The Clemens maid Katy Leary also described Countess Massiglia, "This American

Countess was very disagreeable, and made everything awful hard for them. She

was mad at having to rent her villa, 'cause she had to live in the stable herself;

so she done everything she could to make it uncomfortable for us" (7).

CLEMENS WRITES AND DICTATES

On December 4, 1903 Clemens described the Italian villa in a letter to William Dean Howells:

It is rather comfortable (as European comfort goes), though God himself couldn't start through it on a given excursion & not get lost. It is a monster accumulation of bricks for $2,000 a year -- furnished. It must have been built for fuss & show & irruptions of fashion, not for a home. There are 20 large chambers on the top floor, but they are for servants. Our own floor (ground floor) is cut up into 21 rooms, passages, corridors, &c., & the floor above us is cut up into 22 of the like useless things (the house is 200 feet long) - yet if you were to come I could not find you a comfortable & satisfactory place (8).

Clemens arranged to write magazine articles for Harper publications while in Italy and his first article titled "Italian Without A Master" appeared in the January 2, 1904 issue of Harper's Weekly. It was a humorous look at the Italian language and made no mention of the fact that he was involved in an ongoing round of battles with his local landlady.

A few weeks later Clemens spoke of Countess Massiglia in autobiographical dictation in January 1904:

She is excitable, malicious, malignant, vengeful, unforgiving, selfish, stingy, avaricious, coarse, vulgar, profane, obscene, a furious blusterer on the outside and at heart a coward. … It is good to be a real noble, it is good to be a real American, it is a calamity to be neither the one thing nor the other, a politico-social bastard on both counts (9).

Throughout January 1904 the situation between Clemens and the countess continued

to worsen. Countess Massiglia complained that Clemens had not gotten her permission

to install a telephone in the villa and claimed the telephone company had damaged

her property when they arrived to install one. In a reply to her dated January

19, 1904 Clemens explained the phone was an undesirable necessity for calling

doctors who attended to Mrs. Clemens. On the copy of his letter to the countess,

Clemens noted, "I had her oral consent long ago, but hadn't the wit to

ask her to put it in writing" (10).

LAWSUITS, A DONKEY ATTACK AND MORE VENOM

The situation with the Countess continued to deteriorate when Clemens discovered that the horse stables assigned for his family's use were those in the basement of the house itself, directly under Mrs. Clemens's bedroom. The countess's real estate agent was unable to collect his commission for the rental from her and included Clemens's name in a lawsuit he filed to recover fees due. Other disputes arose when the countess took over control of the water to the villa and drinking water could only be obtained by requesting it from her steward. The empty supply tanks in the upper portion of the house made it impossible to flush toilets. In February a donkey belonging to the countess chased Isabel Lyon who described the donkey attack in her diary:

the Countess's donkey, a creature that has killed his 2 men, suddenly appeared before me … I knew that if he could get at me he would kill me … Like one in a nightmare I fled up the long winding hill, but before I reached the top my heart began to fail me. … For 5 days I lay like one in a dream, but soon I pulled myself together enough to go unsatisfactorily about my work (11).

Clemens reported the donkey incident in a letter to Frederick Duneka on Feb. 8, 1904 and said his writing had come to a "sudden standstill" as a result of a donkey attack on his secretary. Both Lyon and an Italian peasant whose thumb had been bitten off by the donkey a few weeks earlier were encouraged to file lawsuits against the countess. Clemens also threatened to have the villa condemned when he learned the household sewage collected in cesspools under Mrs. Clemens's bedroom.

In retaliation Massiglia evicted Isabel Lyon and her mother from their cottage on the villa grounds and they took up residence with local priest Don Raffaello Stiattisi who became a trusted friend of the Clemens family.

On February 25 and 26, 1904 Clemens wrote Henry Rogers:

Well, we have been in a sweat for a month! The Countess Massiglia (the American bitch who owns this Villa) found that she could afflict me will all sorts of trivial and exasperating annoyances because I couldn't raise a row lest it get to Mrs. Clemens and giver her a fatal backset; and couldn't leave the place because Mrs. Clemens cannot be moved from her bed -- but at last when the Countess ordered the telephone company to remove my telephone (I had just got it in and needed it to send hurry-calls to doctors with), it was one feather more than I could stand. I got the weightiest lawyer in Italy, and game was called.

The Countess is doing the sweating, now. She "hollered" yesterday -- but it is too late. She has made my life a burden to me for 3 months. ...

I expect to drive the Countess off this place (she lives over her own stable, 50 yards from one end of the Villa.) Her presence poisons the whole region. I am backing some peasant-suits against her -- 2 civil and one criminal -- and when those are through I have some more up my sleeve. She appealed to the priest, yesterday, to placate me and call me off -- which he declined. He and I are good friends. She hasn't any.

I expect to move out of this Villa as soon as Mrs. Clemens can be moved. … I shall leave Quarto, but I expect to drive the Countess off the place first. She knows that if I leave it she will have a difficult time trying to rent it again -- for she knows I will prove to any applicant that he will be an ass to take it on any terms (12).

Clemens was convinced the Italian peasants detested Countess Massiglia as much as he because she had evicted them from the estate. History and custom allowed peasants to work ancestral lands by ancient rights of continued usage and loyal service to the landowners. He began writing manuscripts about the countess that remain unpublished. Catalogued as DV #350 in the Mark Twain Papers at Berkeley and titled "The Countess Massiglia" consists of 6 leaves of manuscript. "The Countess Ribaudi-Massiglia (The Reality)" consists of 25 pages of manuscript. Clemens biographer Arthur Scott describes the manuscripts:

He dipped his pen once more in hell and wrote dozens of scorching pages about her alleged treachery, rascality, foul language, and wanton malignity. All winter he drove around the hills of Florence searching for another villa to lease. He was dissuaded with difficulty from suing the Countess for fifty thousand pounds. Never in his life, perhaps, had he spent so much time reviling a person of no consequence to the world (13).

CLARA CLEMENS'S OPINION OF COUNTESS MASSIGLIA

Clara Clemens wrote at length about her father's frustrations and tribulations with Countess Massiglia in her biography My Father Mark Twain. These included cut telephone wires, locked gates, water shortages, and a nasty joke involving the countess's dogs. Clara disguised the countess's identity in her biography by referring to the countess as "Mrs. A____."

The arrangements for our arrival were made by a friend of Father's, Mr. Gregory Smith, who lived in Florence. He had spared no pains to insure the comfort of my parents. Indeed, nothing had been forgotten except the complete deportation of the landlady. Mrs. A_____ was expected to leave town as soon as she rented her villa, but she had changed her mind. There were a few rooms over the stable in which she planned to spend a large part of the season. She was an American of the type one sees oftener abroad than at home. Her husband, an Italian, was somewhere in the Far East.

To start off with, Mrs. A_____ had removed for her own convenience to the apartment over the stable, many things that had been included in the furnishings of the villa when it was rented by Mr. Smith. Father's eyes began to crackle at this information. However, we really had all that we needed, because it was easy to borrow from one room to complete the comforts of the next, there being something like fifty or sixty rooms altogether, in that spacious villa which had been built by one of the Medici and was at one time occupied by a Russian grand duke. … It was decided that the stables where the landlady was residing should not be used, and our horses were housed in a stable under Mother's bedroom. …

A week or two later Mother had an acute heart attack and the nurse rushed to telephone for a doctor. In vain. Impossible to raise an operator. Father, very much excited, got the overseer of the place to accompany him on a trip of investigation through the house and grounds. The telephone was dead. What could be the trouble? It was discovered that the wires had been cut. And by whom? Surely a mystery. One of the servants had to walk a long distance to find a telephone, and toward the end of the day reached the doctor at last. It took three-quarters of an hour to drive to our villa from Florence. We expected the physician to arrive about seven o'clock. But he did not come. Half past seven; still no doctor. Father, growing anxious, started out to the road to see if there was any sign of him. Two sets of high iron gates inclosed our grounds. … Father passed through the first gate, which was wide open. He walked along the winding road, hoping at every turn to meet the doctor. But he had a long walk and met no one. Finally he reached the end of the road and noticed that the iron gate opening into the street was closed. He started to open it. Locked. What on earth could this mean? There was an iron door beside the gate for the use of passengers. This was also locked. Now Father adopted a different pace. Talking to himself and running as fast as a boy, he arrived breathless at the house:

"The doctor has been here and gone. Couldn't get in. Outer gate locked. … WHY was that gate locked? Is some one spying on us? And if so why should they wish to prevent the doctor's arrival?'' …

Mother had, of course, recovered long before from the attack, but we were anxious to have a doctor see her as soon after as was possible. The next day we discovered that he had been at the outer gate and waited nearly an hour, making all the noise he could to attract the attention of some one, but succeeding only in drawing a small crowd of passers-by.

Things went along smoothly for a few days, when one of the maids came to my room early one morning and told me there was no water to be had for washing or cooking. …

We engaged a man to cart water to the house from a near-by spring. This was done for several days while the cause for the sudden absence of this necessary liquid was investigated. It began to look as if our delicate-spirited landlady was the instigator of these evil tricks. And her ingenuity was fertile.

Father was at home sometimes in the afternoon at tea-time to callers of various types and races, but he never had encouraged the landlady to call. Jean used to be amused to see the slats of the green shutters in the windows over the stable blink open and shut while Father's guests drove in and out of the gate.

Mrs. A_____ kept a couple of very ugly dogs which were rarely seen in our part of the grounds, but Jean and I thought it well to make friends with them, which we finally accomplished after a good deal of effort. It happened one day that Jean had asked three or four young friends to prolong their call and stay for supper. They were dressed in light clothes, both the boys and the girls. We went onto the terrace and after watching the setting sun, decided to stroll along the road in the darkening light. The shutters above the stable trembled once more and a few minutes later we were startled by the violent barking and bustling of dogs in pursuit of us. Jean and I were frightened, because we thought the dogs might not recognize us in the dim light and I had not forgotten an experience I had had with the same kind of vicious bulldog several years before. As they approached us we began to call to them with endearing expressions on our tongues and honey in our voices. What magic lies in the pitch of tone! The dogs began to slow down and then uncertainly wag their tails, when suddenly with a joyous bound they poured out their affection by rubbing themselves against our lovely dresses. What is all this moisture and this penetrating smell? It can't be oh, it can't be, but it was kerosene oil. And apologies to our guests seemed inadequate.

It was clear enough by this time that the evil genius was living right in the same grounds with us in loving proximity, and intended to spend the season in her own original way. Therefore Father called on a lawyer and succeeded in having Mrs. A_____ ejected from our vicinity. It seemed almost too bad to spoil her fun (14).

DEATH OF OLIVIA CLEMENS

At the end of March 1904, Clemens was becoming more adjusted to life at the villa and wrote:

Now that we have lived in this house four and a half months my prejudices have fallen away one by one & the place has become very homelike to me. Under certain conditions I should like to go on living in it indefinitely. I should wish the countess to move out of Italy, out of Europe, out of the planet. I should want her bonded to retire to her place in the next world & inform me which of the two it was, so that I could arrange for my own hereafter (15).

In June 1904 the Critic magazine published an article by Raffaele Simboli about Clemens's time in residence at the Villa di Quarto along with photographs of Clemens. Simboli misspelled the countess's name when he wrote about Clemens's lease, "His lease of the Villa di Quarto is only for a year, but Signora Marsili, the owner, thinks that he will renew it when it expires, since he is so well and comfortable in Florence, and since his wife's health has already shown a marked improvement."

Olivia Clemens died June 5, 1904 at the Villa di Quarto and Clemens returned

to the United States. He never again returned to Italy. His article "Italian

With Grammar" appeared in the August issue of Harper's Monthly.

It was a second essay written in a humorous vein reflecting on the Italian language.

The article makes no mention of the underlying tensions with Countess Massiglia

he had experienced for the duration of his time at Villa di Quarto.

PUBLIC INSULTS

After regaining possession of her villa, Countess Massiglia claimed the Clemens family had caused eight hundred francs' damages to her home. Clemens lashed back at the Countess Massiglia in a public reference to her in the January 1905 issue of North American Review in an article titled "Concerning Copyright." In criticizing the copyright laws he wrote they accomplish "Nothing useful, nothing worthy, nothing modest, nothing dignified, nothing honest, so far as I know. An Italian statesman has called it "the Countess Massiglia of legal burlesque" (16).

The following month on February 6, Father Raffaello Stiattesi wrote to Clemens from Italy that the countess was engaged in slandering him and his lawyers in an enormously disgusting manner. Stiattesi wrote, "for God's sake be upon your guard and take well what I write you as an independent, honest, calm friend." Stiattesi further recommended that Clemens pardon her and forget the injuries (17).

Clemens replied on Feb. 19, 1905, "Forgive her? Yes, I am quite able to do that, but it would do no good, she would not understand it. The insane seldom understand words or actions that proceed from a moral basis" (18).

It was also during this time frame, between November 1904 and February 1905 that Clemens composed a manuscript titled "Flies and Russians" which remained unpublished during his lifetime. He wrote of the mistakes that mother nature has made. In his original manuscript he wrote:

Next she tried to make a reptile that could fly. We know the result. The less said about the pterodactyl the better. It was a spectacle, that beast! A mixture of buzzard and alligator, a kind of Countess Ribaudi Massiglia: a sarcasm, an affront to all animated nature, a butt for the ribald jests of an unfeeling world (19).

Clemens later marked through the reference to the countess.

THE LAWSUITS FIZZLE OUT

In May 1905 Count Massiglia was assigned to New York as Italian Consul General. In a possible effort to put an end to the feud between his wife and Clemens, a feud which had the potential to create embarrassment in the American press for him, Count Massiglia tried to bring an end to the various lawsuits Clemens was backing against his wife.

In a November 29, 1905 entry in her journal Isabel Lyon wrote:

This afternoon at 3:30 Signor Traverso came in to tell Mr. Clemens about the Massiglia lawsuit. All the misery that Mr. Clemens ever hoped the Countess would get out of this suit she has got, for she has spent a lot of money, the lawyers have taken their time about getting evidence (or taking testimony) and long ago Count Massiglia went to Signor Traverso begging him to ask Mr. Clemens to drop the suit, for it was killing his wife and life at the villa was made impossible for them, for every hand was against them and life had become a Hell. Mr. Clemens listened to Traverso's story, with a keen satisfaction, for the Countess has garnered what she sowed (20).

Clemens was content to let the countess roast in hell. He allowed the lawsuits to continue against her into at least 1906. Lyon again recorded in her journal on August 25, 1906:

The lawyers aren't going to say that the suit is given up -- for you can't ever say what such as the Massiglia might do. They might suddenly become the assailers, instead of the assailed" (21).

After 1906 Countess Massiglia ceased to be a major target for Clemens's vilification. His relationship with his secretary Isabel Lyon crumbled a few years later when he became convinced Lyon had plotted to keep his daughter Jean away from him and had also helped herself to some of his personal finances. Lyon became a target for his wrath. He compared Lyon to the countess:

I used to consider the Countess Massiglia the lowest-down woman on the planet. Well, when I get through examining Miss Lyon I shall realize I have been doing the Countess a wrong (22).

AFTERWORD

Count Massiglia's next diplomatic assignments were in Mexico, Cuba, and Haiti. He retired from diplomatic service in 1915 (23). Count Raybaudi Massiglia died in Rome on March 2, 1942. Frances Lloyd Paxton, the Countess Massiglia, died April 16, 1953 in Rome. Information from the National Archives indicates her remains were to be sent for burial to the "Friends Burying Ground" in Darby, Delaware County, Pennsylvania where her parents were buried (24). She ranks among women as one of Mark Twain's most detested.

2010 UPDATE

Available from amazon.com |

In October 2010, the centennial year of Samuel Clemens's death, the University of California Press issued Volume 1 of Autobiography of Mark Twain. The book contains the full text of Clemens's dictations from January 1904 regarding the Countess Massiglia. "I was losing my belief in hell until I got acquainted with the Countess Massiglia" he declared. |

_____

REFERENCE NOTES

(1) United States passport application from ancestry.com dated Nov. 26, 1888. It should be noted that other unofficial sources give her birthplace as Darby, Delaware, PA.

(2) Information on Count Massiglia's diplomatic career is from La Formazione Della Diplomazia Nazionale (1861-1915) : Repertorio Bio-bibliografico Dei Funzionari del Ministero Degli Affari Esteri. Università degli Studi (Lecce); Dipartimento di Sc, 1987.

(3) "The New Italian Consul," Philadelphia Inquirer, October 16, 1889, p. 6.

(4) Hill, Hamlin. Mark Twain: God's Fool. Harper & Row, (1973), p. 70.

(6) Willis, Resa. Mark and Livy. Atheneum Publishers, (1992), pp. 2-3.

(7) Lawton, Mary. A Lifetime with Mark Twain. Harcourt, Brace and Company (1925), p. 223.

(8) Clemens, Samuel to William Dean Howells, December 4, 1903. Published in Mark Twain - Howells Letters, Vol. 2. Edited by Henry Nash Smith and William M. Gibson. Belknap Press, (1960), p. 775.

(10) Clemens, Samuel to Frances Massiglia, January 19, 1904. Text courtesy of the Mark Twain Papers and the James S. Copley Library, La Jolla, California.

(12) Clemens, Samuel to Henry H. Rogers, February 25 - 26, 1904. Published in Mark Twain's Correspondence with Henry Huttleston Rogers, 1893-1909. Edited by Lewis Leary. University of California Press (1969), pp. 557-558.

(13) Scott, Arthur L. Mark Twain at Large. Henry Regnery Company (1969), p. 274.

(14) Clemens, Clara. My Father Mark Twain. Harper & Brothers (1931), pp. 241-246.

(15) Paine, Albert Bigelow. Mark Twain: A Biography. Harper & Brothers (1912), pp. 1213-1214.

(16) Twain, Mark. "Concerning Copyright," North American Review, January 1905, pp. 1-8. Reprinted in Mark Twain: Collected Tales, Sketches, Speeches, & Essays, 1891-1910. Edited by Louis J. Budd. Library of America (1992), p. 628.

(17) Stiattesi, Raffaello to Samuel Clemens, February 6, 1905. Typescript from the Mark Twain Papers, University of California at Berkeley.

(19) Twain, Mark. "Flies and Russians." Reprinted in Fables of Man. Edited by John S. Tuckey. University of California Press (1972), pp. 423, 730.

(22) Twain, Mark. "Ashcroft-Lyon Manuscript," p. 37 Quoted by Andrew Hoffman in Inventing Mark Twain. William Morrow and Company (1997), p. 492.

(23) Cypull Adys and Froilán González. Julio Antonio Mella y Tine Modotti: Contra El Fascismo. Ciudad de la Habana, Cuba : Casa Editora Abril, 2005). The same info regarding Massiglia's retirement is in: La Formazione Della Diplomazia Nazionale (1861-1915) : Repertorio Bio-bibliografico Dei Funzionari del Ministero Degli Affari Esteri. Università degli Studi (Lecce); Dipartimento di Sc, 1987.

(24) State Department (RG 59): Central Decimal Files, 1950-54, 265.113 Massiglia, Frances Paxton Raybaudi/4-1853 in box 1101.