|

|

|

|

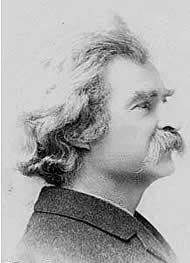

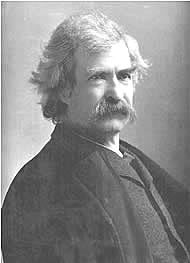

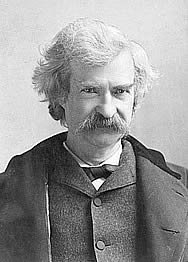

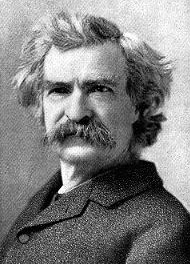

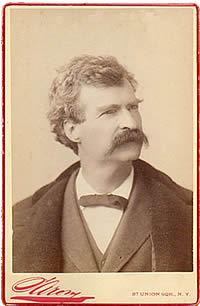

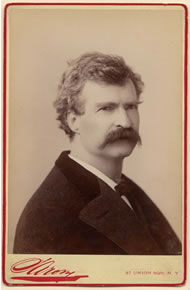

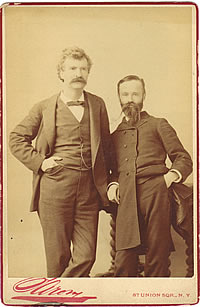

Photos

of Mark Twain believed to be from an 1893 photo session with Sarony.

After initially approving of the photo on the far right, Clemens later referred

to it as "The damned old libel."

Some of the most famous photographs of Samuel Clemens, better known as Mark Twain, were made by New York photographer Napoleon Sarony. No complete record exists of exactly how many negatives Sarony made of Clemens nor how many photo sessions Clemens had with him. There were at least two sessions -- a session about 1884 and a second session about November 1893 when Clemens intended to have a photo of himself made for his wife Livy's birthday on November 27. On November 18, 1893 Clemens wrote from New York to his wife Livy:

I am desperately disappointed because my photograph is not ready for your birthday. I was going to send it to Susy & have her put it with the other tokens of love & remembrances Nov. 27th. But I see I can't manage it now. I went there & sat 7 times & got one or two very good negatives. Sarony should have had the pictures here two days ago but he has failed me (Wecter, p. 278-79).

Clemens apparently initially approved of the photo he came to detest, inscribing a copy to his wife: "November 27-- a date dear to/ SLC/ 1893." The inscribed photo is in the Kevin Mac Donnell collection. Demorest's Family Magazine for December 1894 used a different one from the 1893 session (second from the left above) in their feature article "Off-Hand Chats with Professional Humorists."

Napoleon Sarony

Napoleon Sarony was born about 1821 in Quebec, Canada, the same year that his namesake Napoleon I died at St. Helena. Information on Sarony's family and early childhood background is sketchy. Historians have reported that his father, a lithographer, had immigrated to Canada from Birmingham, England. Sarony's mother died when he was about ten years old causing the family, which included eight children, to disperse. Napoleon Sarony arrived in New York state in the 1830s and worked as a lithographer with Henry R. Robinson and Nathaniel Currier (of Currier & Ives fame). Sarony eventually established his own firm in partnership with Henry B. Major and in 1846 he married Ellen Major (b. about 1830, possibly a sister to Henry). The 1850 census for Kings, Williamsburg, New York shows Napoleon and Ellen living in the Henry Major household along with the Sarony children Ida, age two and son Otto, age seven months. In 1857, Joseph F. Knapp joined the partnership to form the Sarony, Major & Knapp lithography company. The partnership became one of the country's most successful in the field and later evolved into American Lithographic Company.

By the time Ellen Sarony died in January 1858, Napoleon had amassed enough wealth to take his children to Europe where he studied art in Berlin, Paris and London. After visiting his older brother Olivier (b. 1820 - d. 1879) in Scarborough, England and seeing the enormous financial success Olivier was having in portrait photography, Sarony felt he could do the same. At the end of the U.S. Civil War, Sarony returned to the States and in 1865 opened his first photography studio in New York City at 630 Broadway, later moving it to 680 Broadway.

Recognizing a market for celebrity photos, Sarony was one of the first photographers to implement the practice of paying well-known individuals to pose for him and then retaining the rights to sell their photos for profit. As a business practice, Sarony wrote personal letters to well-known public personalities inviting them to his studio for a photo session. And in 1871, Samuel Clemens also known as "Mark Twain" fit the profile of a potential client. Clemens was an established author with the recent success of his book The Innocents Abroad. Clemens had recently completed a lecture tour across the northeast and had been a regular contributor to the Galaxy magazine. The following letter to Samuel Clemens is likely typical of the solicitation letters Sarony wrote:

Napoleon Sarony

letter to Samuel Clemens is courtesy of the Mark

Twain Papers, University of California, Berkeley.

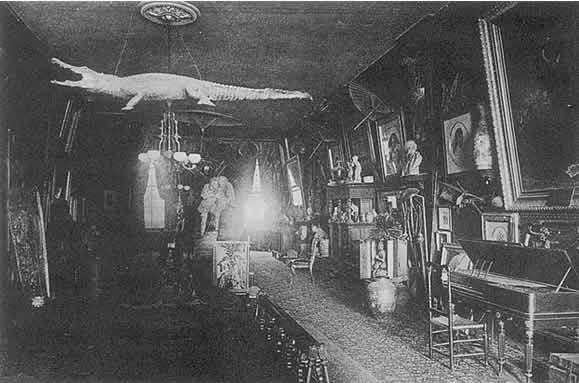

In late 1871 Sarony moved his studio to 37 Union Square where it occupied several floors above the ground level. Rental on the Union Square building was $8,000 a year (an equivalent of over $116,000 in year 2006). Customers rode a small slow-moving hydraulic elevator up from the street level to Sarony's reception room located on the fifth floor. Richard Grant White, writing for the Galaxy magazine described Sarony's studio as "Glare, bareness, screens, iron instruments of torture, and a smell as of a drug and chemical warehouse on fire in the distance. A photographer's operating room is always something between a barn, a green-room, and a laboratory" (from "A Morning at Sarony's" in Galaxy, March 1870, p. 409.) The "iron instruments of torture" were posing braces and stands to help the subject remain motionless for exposure times which often ranged from fifteen seconds up to a minute. Sarony's involvement in the portrait making was primarily in arranging the camera, extracting the right expressions from the face and body of his subject, lighting, drapes, and props -- the art of the photo. Numerous assistants were on his staff to attend to the mechanical chores of the camera operation and the chemical processes involved.

Sarony's reception

room at 37 Union Square.

Sarony considered himself an artist above all else -- preferring to draw with charcoal and crayon. However, with his innovative techniques in application of lighting, posing his subjects, and arranging background elements in portraits he rose to prominence. When once interviewed about his work, he stated "We photographers have queer experiences. Ours is a most excellent opportunity to study human nature, and making a baby laugh is not the one trick of the calling. In order to take a good photograph one should know something about the sitter's habits and surroundings. This he must learn at a single glance or by an adroit question." (From an interview in Newark Sunday Advocate, January 7, 1893, p. 2. Reprinting the New York Herald.)

|

|

Sarony was short, small and wiry -- about five feet tall with bowed legs. What he lacked in stature was compensated by a freshness and ingenuity and a high energy level most often found in children. He wore a mustache and goatee which enhanced his resemblance to Emperor Napoleon III. In his youth, Sarony had been fond of sports and was considered an able oarsman. He was lively and quick in conversation and known for emphasizing his conversations with rapid gestures of his arms and legs. And he had the knack of getting famous performers to perform before his camera. At the peak of his career, Sarony married a second time to Louise Thomas, sister of lithographer Henry Thomas. He became a familiar figure on upper Broadway and was often seen on daily strolls arm-in-arm with his wife. He often wore a fez which covered a balding head, and both he and his wife dressed in picturesque and attention-getting attire. After all, gathering attention to himself was a form of advertising. (Additional photos of Sarony and his wife Louise can be found online at www.picturehistory.com.) |

Sarony, Oscar Wilde and the Supreme Court

Sarony entered into U.S. copyright history when he successfully upheld a photographer's right to claim copyright protection on his own photographs as an original work of art. The 1883 case known as Sarony vs. Burrow-Giles Lithographic Company was argued before the State District court in New York and involved the unauthorized reprinting of Sarony's photograph of Oscar Wilde for a department store advertising campaign. Sarony won in state court and Burrow-Giles appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. The copyright case received press coverage, some of which may have caught the attention of Mark Twain who had fought his own battles for copyright protection for authors.

|

The New York Times, December 14, 1883, p. 4 DID SARONY INVENT OSCAR WILDE? WASHINGTON, Dec. 13 - The case of the Burrow-Giles Lithographic Company against Napoleon Sarony, which was argued in the United States Supreme Court this afternoon, related to a photograph of Oscar Wilde, and involved the question whether the copyright acts, in so far as they grant protection to photographs, are constitutional, Counsel for Mr. Sarony argued that the latter had "invented" the picture in controversy, that is, that he had posed Oscar Wilde before the camera, selected his costume as well as the draperies and other accessories, "arranged the said Oscar Wilde in a graceful position, and suggested and evoked the desired expression." This, counsel maintained, made Mr. Sarony an author or inventor, not of the subject of the picture, it was true, but of the picture itself. Counsel for the lithographic company, however, contended that Mr. Sarony had not produced or invented Oscar Wilde, but had merely arranged him, that is, had newly arranged something already extant. If this was invention, Mr. Sarony had mistaken his remedy; he should have taken out a patent instead of a copyright. To obtain a copyright the person claiming protection must be the author of the visible article on which the copyright is granted. Mr. Sarony was not the creator of Oscar Wilde, and a photograph was not such an original as could be copyrighted. All that the photographer did was to put Mr. Wilde in a particular suit of clothes and have him cross his legs in a particular fashion. That work was not the work of an author, and Mr. Sarony was not entitled, counsel maintained, to copyright protection. |

The Supreme Court did not agree with the arguments of Burrow-Giles and ruled in Sarony's favor on March 17, 1884. (Mitch Tuchman writing for Smithsonian Magazine in a May 2004 article titled "Supremely Wilde" provides one of the best summaries of the history behind the photo dispute that is available online.) In 1890 Sarony photographed the members of the Supreme Court in his New York studio. Most of the justices who had decided the case in his favor were still serving on the bench. (See Sarony's 1890 Supreme Court photo online at this site.)

Sarony, Mark Twain and George Washington Cable - 1884

|

|

|

|

Samuel Clemens and Sarony moved in overlapping social circles and had mutual acquaintances. Both men were members of the Lotos Club of New York City. Sarony had helped establish the Salmagundi Club which was an association of artists and he was a member of the Tile Club which included well-known figures of literary prominence. Clemens had been a guest of the Tile Club on December 20, 1880 in the studio of Francis Hopkinson Smith. However, there is no record verifying Sarony was in attendance that evening. (Smith's book The Fortunes of Oliver Horn published in 1902 featured the character Julius Bianchi which was based on Sarony.) In 1883 Wilkie Collins dedicated his anti-vivisection book Heart and Science to Sarony. In 1884 Sarony was a participant in an April Fool's joke played on Clemens when George Washington Cable arranged for 150 of Mark Twain's friends to write to him simultaneously requesting his autograph. As part of the joke, no stamps or envelopes were to be provided for a reply. Misspelling Clemens's name, Sarony sent a note to "My dear Clements":

Napoleon

Sarony letter to Samuel Clemens is courtesy of the Mark

Twain Papers, University of California, Berkeley.

Clemens and George Washington Cable were photographed by Sarony prior to the fall of 1884. In September of 1884, Clemens wrote to artist and sculptor Karl Gerhardt asking him to create a clay medallion of himself and Cable based on Sarony's photographs -- possibly to be used in advertising the "Twins of Genius" lecture tour which began in November 1884.

|

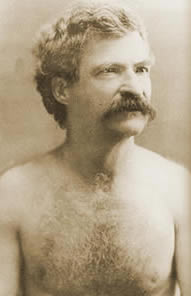

It was formerly thought that the barechested photo of Clemens taken in 1884 was made by Sarony. However, additional research from the editors of the Mark Twain Project in September 2010 has established the probability that this photo was taken in August 1884 by Charles Tomlinson, an "artistic" photographer, from Elmira, New York. Twain scholars have long believed the bare-chested photo was used by sculptor Karl Gerhardt for a bust -- a photo of which was used as a frontispiece in the first edition of ADVENTURES OF HUCKLEBERRY FINN. |

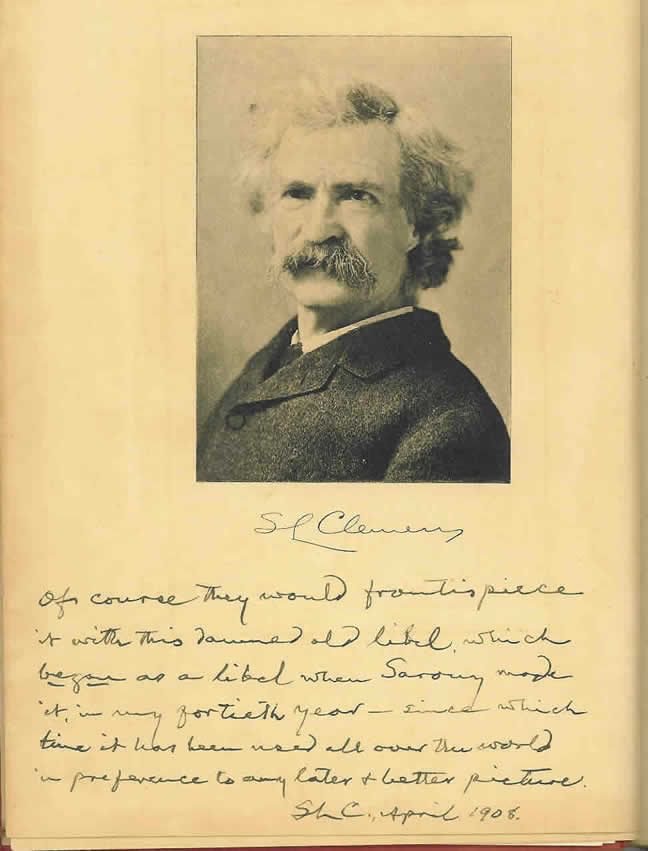

"The Damned Old Libel"

While Sarony's work pleased the eyes of the world, not all of his photos of Clemens were met with his approval. When Clemens was honored by Harper and Brothers on his sixty-seventy birthday in 1902, a book was compiled for those in attendance. The frontispiece for the slim volume was a Sarony portrait of Clemens. Six years later, in his personal copy of the book Clemens recorded how he really felt about the photo:

Clemens's personal

copy of the sixty-seventy birthday souvenir book is in the Kevin

Mac Donnell collection.

Photo courtesy of Kevin Mac Donnell.

Clemens wrote:

|

of course they would frontispiece it with this damned old libel, which began as a libel when Sarony made it, in my fortieth year -- since which time it has been used all over the world in preference to any later & better picture. SLC., April 1908 |

The photograph used as the frontispiece in the birthday book was not made in Clemens's "fortieth" year (which would have been 1875). This comment was a typical Mark Twain exaggeration. The photo had been made at the later session of 1894 when Clemens was about sixty. While it is not possible to identify with total accuracy, it is likely the same photograph that Clemens had complained about when he replied to Mr. Samuel H. Row of Lansing, Michigan in a 1905 letter:

| November

14, 1905.

Dear Mr. Row, That alleged portrait has a private history. Sarony was as much of an enthusiast about wild animals as he was about photography; and when Du Chaillu brought the first Gorilla to this country in 1819 he came to me in a fever of excitement and asked me if my father was of record and authentic. I said he was; then Sarony, without any abatement of his excitement asked if my grandfather also was of record and authentic. I said he was. Then Sarony, with still rising excitement and with joy added to it, said he had found my great grandfather in the person of the gorilla and had recognized him at once by his resemblance to me. I was deeply hurt but did not reveal this, because I knew Sarony meant no offense for the gorilla had not done him any harm, and he was not a man who would say an unkind thing about a gorilla wantonly. I went with him to inspect the ancestor, and examined him from several points of view, without being able to detect anything more than a passing resemblance. "Wait," said Sarony with strong confidence, "let me show you." He borrowed my overcoat and put it on the gorilla. The result was surprising. I saw that the gorilla while not looking distinctly like me was exactly what my great grandfather would have looked like if I had had one. Sarony photographed the creature in that overcoat, and spread the picture about the world. It has remained spread about the world ever since. It turns up every week in some newspaper somewhere or other. It is not my favorite, but to my exasperation it is everybody else's. Do you think you could get it suppressed for me? I will pay the limit. Sincerely yours, S. L. Clemens. |

In the spring of 1894 newspapers carried an article by Sarony wherein he commented about his snapshots of famous clients, including Mark Twain.

|

(Boise) IDAHO DAILY STATESMAN, April 12, 1894, p. 4. FAMOUS

SNAP SHOTS. [Special Correspondence.] NEW YORK. March 19. -- Mr. James G. Blaine was sitting in my studio one day in the autumn of 1884, waiting to have his picture taken. It was the very day -- in fact, it was the very hour following that in which was let slip those famous and fatal words -- rum, Romanism and rebellion. My representative, who had been waiting for him at the Fifth Avenue hotel brought the great statesman to the studio in a carriage, and while waiting for me to adjust my camera he reeled off a story or two with his keen sense of humor and with unusual light heartedness, all unaware that at the same time Archbishop Corrigan was being informed of Burchard's silly speech made that day and while a circular was being prepared which lost Mr. Blaine the election. "Are you ready to take my picture?" he said when he had finished his story. "It is taken," I replied. I had caught him just at the right moment, when he was reaching the climax of the story, and his photograph is quite the best I have ever taken of him. Caught on the Fly. A snap shot picture indeed is very often better than one taken with considerable study. When I say snap shot, I mean, of course, simply an instantaneous picture taken in the studio, and I mean the taking a man's photograph when he doesn't know it. A photographer who risks a snap shot should already have studied his subject, should be familiar with his habits and surroundings and should know the one position in which his man appears at the best. The moment a man is told to "look natural, please," that very moment the poor man will look perfectly miserable. He feels that he is posing. He is self conscious, an element always sure to affect a photograph the wrong way. Strange as it may seem, this is the very reason that Dr. Depew has never had a picture taken that does him justice. He never looks natural. If he could be caught unaware some time, during a political speech or in a merry moment when he is reaching the point of an after dinner story, Depew could then see himself in a photograph as he really is. It is evident, therefore, that some men can be photographed to look naturally only by means of a snap shot. But the shot must be made by a sharpshooter. The game cannot be bagged by any slouchy sportsman. There is always on certain position in which a man appears at his best. This one position the photographer must find, and that quickly, and seize his opportunity to take a picture the moment the man is in that position. When Mr. Wilkie Collins came to me, I discovered at once a peculiarity of facial expression when he talked about his own books which was most interesting, so while he answered kindly a question or two from me about his "Woman In White" I made a quick exposure, feeling that I had taken the great novelist at his best, and so it proved. When he returned to England, he wrote me: "You have taken just the sort of photograph I like. Those taken of me over here are perfect libels, but I feel like giving your pictures to all my friends." Mark Twain and Sir Edwin Arnold. The last picture I made of Mark Twain was also a snap shot and was also the best I have taken of him. I met the humorist on the street. His long iron gray hair tumbled over his coat collar and stuck out from under his hat, giving his head a massive appearance of the old type of patriarch. "Mark Twain," I said, catching hold of him, "I want you to let me take your head just as it is. Don't go to the barber until you see me." He consented and came to my studio in a few days, when I secured a photograph of which I am justly proud. Another instance: Sir Edwin Arnold soon after his arrival here came to me saying: "Sarony, I want you to make a photograph of me wherein my nose shall be a straight nose. The English photographers," he went on, "Have never made that feature look right in my photographs. Now, can you?" I observed him attentively a moment, and then I said, "Sir Edwin, when you were a baby you sucked your thumb, pressing your forefinger against the right side of your nose and making there an indentation which to a trained eye is still perceptible." Then I simply photographed the left side of Sir Edwin's face instead of the right side -- the side which the English photographers had evidently insisted upon taking. I have often had people to ask me which side of a person I usually photograph. The they will add: "The right side, of course. That's always the best side, isn't it?" And this absurd statement has more than once been made by persons whom I had every reason to suppose were perfectly sane. President Cleveland's Last Picture. Another essential in making a snap shot, if it is to be successful, is magnetism. A silent chord must be struck. There must be harmony or sympathy, or whatever you may choose to call it, between the sitter and the photographer. I myself must be in perfect sympathy with my subject before I can make a good picture. This accounts for the difference between the first photographs which I took of Mr. Cleveland and the last. When he first came to sit for me, he was cold, reserved and haughty. Accordingly the photograph which I made of him bespoke those characteristics. Not so the last ones, however, for on this occasion he grasped my hand with great warmth and said very cordially, "Napoleon, I can't stay away from you." At last we were friendly, and the photographs taken on that occasion show the friendliness of the man. Now as to the artistic essentials. In the first place, is the photographer an artist? This question has been discussed for years, but we have arrived no nearer to a decision than we were at the beginning. Many persons claim that photographers are artists in picture making and entitled to the same standing as those who paint on canvas. Debaters on the negative side argue that photography, in an aesthetic sense, must stand entirely and unreservedly apart from painting to almost as great an extent as sculpture. They claim, further, that the majority of photographers are not noted for their excellence in drawing -- most of them can't draw at all, in fact -- and that some are even color blind, yet can make fairly artistic photographs. Photography as a Fine Art. As far myself, I agree that photography is an aesthetic art when confined to its legitimate purpose and practiced by men of artistic knowledge and skill. A photographer who possesses these requirements is an artist in his profession, just as is a painter in the profession of painting. It amounts to simply this: The photographer who is also an artist will surely make the best photograph. I have been asked to what one thing I attribute my success in photography? I reply, because I am an artist first. The more artistic taste that can be brought into photography the better will it be for the photographer. The advantage of artistic training was shown to some extent in my photographs of General Hancock. The campaign photographs of the general showed him as wearing a goatee. This was the cause of some wonder, for it was known that General Hancock had not worn this appendage since he had thrown off the uniform of the war period. After I had taken his picture I placed my hand over the lower portion of his face, informing him that he had splendid eyes, a good nose and a strong mouth, but that his chin was weak. "You need a goatee," I said. He assented, and so I drew a tuft of hair over his chin as the negative, thus explaining the warrior's goatee photographs. |

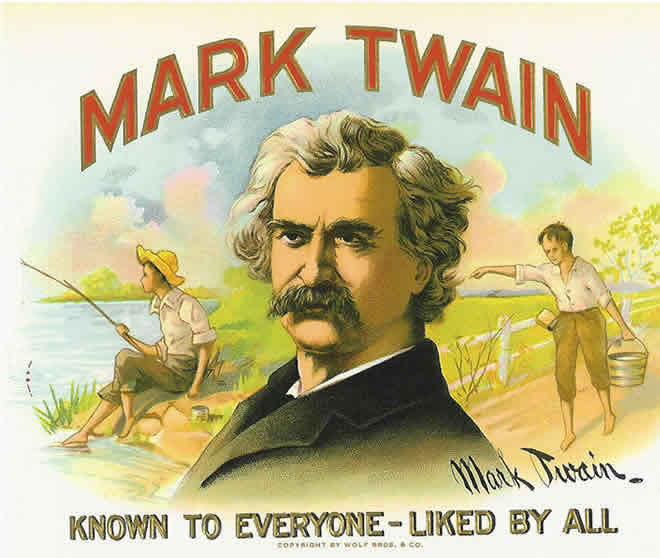

"Known to Everyone - Liked by All"

As much as Clemens disliked Sarony's "damned old libel" photograph, the image found new life in 1913 as a cigar label which remains highly collectible today -- "Known to Everyone -- Liked by All." Not only did the cigar label feature graphic artwork based on Sarony's photograph, it also contained a script-like autograph that was not Mark Twain's.

Mark Twain cigar

label from the Kevin Mac Donnell

collection. Photo courtesy of Kevin Mac Donnell.

Sarony's Legacy

In an interview that appeared in Wilson's Photographic Magazine in 1893 Sarony appeared to show more concern for his old pet parrot who had lately refused to talk than he did with his lifetime of work. His remarks indicated he had "burned out" and lost his enthusiasm for photography: "I burn, I ache, I die, for something that is truly art. All my art in the photograph, I value as nothing. I want to make pictures out of myself, to group a thousand shapes that crowd my imagination. This relieves me, the other oppresses me..." (Wilson's Photographic Magazine, January 1893.)

Napoleon Sarony |

In April 1896, a few months before his death Sarony had moved from the old 37 Union Square address -- the building was scheduled to be torn down. Sarony sold many of his studio props, a collection of curios from countries around the world -- China, Japan, India, Egypt, Patagonia -- armor, idols, shark jaws, bric-a-brack, his own art works and some works of his friends, and even an Egyptian mummy. The American Art Association catalog listed almost one thousand items for the sale. Newspapers reported prices for Sarony's items were relatively low. The grand total sale of his entire collection totaled about $5,000 (about $110,000 in year 2006 dollars.) There is some evidence to indicate that Sarony may also have been in financial difficulties. An undated letter from Sarony to actress Ada Rehan owned by the University of Pennsylvania rare book and manuscript library states, "my balance in bank barely enough to meet expenses." |

At the time of his death, Sarony's studio was located at 256 Fifth Avenue. Sarony died on November 9, 1896 at his home at 126 West Forty-seventh street. His physician Dr. Robert Milbank gave the cause of death as paralysis of the brain. Some obituaries indicated that Sarony had made and lost several fortunes during his lifetime and had died relatively poor. Newspapers estimated he had photographed 30,000 of the world's celebrities and about 200,000 members of the general public. Estimates of the number of negatives that were housed in his studio ranged as high as 500,000. Sarony was buried in Green-Wood cemetery in Brooklyn, New York. According to his will which was dated October 2, 1885, Sarony bequeathed $1,500 to his daughter Mrs. Mary Fry of London and $500 to another daughter Mrs. Jennie Fisher. (Sarony's other daughter Ida had died in childbirth in 1878.) The remainder of his estate was to be divided among his surviving widow Louise, his son Otto, and a daughter named Isabelle who had married Joseph Bonanno in 1885. (Isabelle's parentage is open to question. Genealogy researcher Peggy Wishon, in private correspondence of January 2008, reports finding a birth registration for an Isabel Louise Sarony, registered in Birmingham, England, in 1864. However, the 1870 United States census shows a six-year-old daughter Isabelle, born in Massachusetts, living in Sarony's household. It seems possible she was Louise's daughter prior to her marriage to Sarony. Obituaries reported that Napoleon and his wife Louise had no children together. Isabelle's name was missing from the surrogate notices that appeared in the New York Times in 1897 and it is likely she had died before Sarony.)

Otto Sarony had often worked with his father, but more frequently his name was found in the newspapers in stories about yachting at the local Larchmont Yacht Club.Otto sold the Sarony studio and trademark name October 7, 1898 to John F. Burrow. (The question remains if he was the same Burrow involved in the Supreme Court copyright case.) Otto Sarony found himself in legal trouble when he also sold to Theodore Marceau, the right to use the Sarony name for another photography studio in exchange for one share of the Marceau Company. Otto Sarony died on September 13, 1903 survived by one son Arthur Yale Sarony. Burrow and Marceau continued to fight a legal battle over the use of the Sarony name in a case that was finally decided in favor of Burrow in 1908. Louise Sarony remarried to Domenico Bonanno in 1897 and died on March 8, 1903. As of this date, the fate and/or location of Sarony's life work of possibly half a million original glass negatives remains a mystery.

_____

REFERENCES FOR THIS ARTICLE INCLUDE THE FOLLOWING SOURCES:

Bassham,

Ben. The Theatrical Photographs of Napoleon Sarony (Kent State University

Press, 1978).

"Burial Search: The Green-Wood Cemetery." Database online at: http://www.green-wood.com

viewed 22 July 2006.

Burrow-Giles Lithographic Company v. Sarony. Supreme Court of the United States,

111 U.S. 53; 4 S. Ct. 279; 28 L. Ed. 349; 1884 U.S. LEXIS 1757

"Business Troubles: Otto Sarony Examined," New York Times,

1 April 1902, p. 5.

"City and Suburban News: Isabelle L. Sarony ...," New York Times,

1 December 1885, p. 8.

"A Day's Weddings: Bonanno - Sarony," New York Times, 4 December

1897, p. 7.

"Death of Otto Sarony," New York Times, 14 September 1903,

p. 7.

Ernest M. Burrow, Appellant, v. Theodore Marceau, Respondent, Impleaded with

Otto Sarony Company, Photographers, Defendant. Supreme Court of New York, Appellate

Division, First Department, 124 A.D. 665; 109 N.Y.S. 105; 1908 N.Y. App. Div.

LEXIS 2178.

Hirst, Robert. Personal correspondence, 3 September 2010.

"Freaks of Photography," Indiana (Pennsylvania) Democrat,

8 May 1890.

"Gallery and Studio: A Photographer Who is Also an Artist," Brooklyn

Eagle, 9 August 1885, p. 2.

"In the World of Art," New York Times, 5 April 1896, p. 11.

Mac Donnell, Kevin. Personal correspondence, 29 January 2010.

"Napoleon Sarony," Penn Library Exhibitions, online at http://www.library.upenn.edu/exhibits/rbm/dreiser/sarony.html

viewed 4 August 2006.

"Napoleon Sarony Buried," New York Times, 12 November 1896,

p. 9.

"Napoleon Sarony Dead," New York Times, 10 November 1896, p.

9.

"Napoleon Sarony Dead," New York Tribune, 10 November 1896.

Obituary: "Joseph Bonanno," Brooklyn Eagle, 13 December 1901,

p. 3.

"Off-hand Chats with Professional Humorists," Demorests's Family Magazine,

December 1894, p. 74.

"Personals," Hartford Daily Courant, 21 August 1878, p. 2.

"A Photograph of Beecher," The Newark Sunday Advocate, 7 January

1893.

Pollack, Peter. The Picture History of Photography (Harry N. Abrams,

Inc., 1969).

"Sarony," Wilson's Photographic Magazine, January 1893, pp.

6 - 15.

Sarony v. Burrow-Giles Lithographic Co., Circuit Court, S.D. New York, 17 F.

591; 1883 U.S. App. LEXIS 2303, April, 1883, Term

"Sarony's Funeral," Brooklyn Eagle, 11 November 1896, p. 1.

"Sarony, The Artist, Dead," Brooklyn Eagle, 9 November 1896.

"Sarony's Widow a Bride," Brooklyn Eagle, 03 December 1897,

p. 2.

Scharnhorst, Gary. Mark Twain: The Complete Interviews (University of

Alabama Press, 2006).

"Surrogate Notices," New York Times, 6 January 1897, p. 6.

Taft, Robert. Photography and the American Scene (Dover Publications,

1964).

"To Sell the Sarony Collection," New York Times, 28 March 1896,

p. 3.

Tuchman, Mitch. "Supremely

Wilde," Smithsonian Magazine, May 2004 online edition viewed

21 July 2006.

United States Censuses, 1850 - 1930, online at ancestry.com

viewed 21 July 2006.

Wecter, Dixon, ed. The Love Letters of Mark Twain. Harper and Brothes,

1949.

"What Mr. Sarony Says of Mrs. Langtry and Her Pictures," Chicago

Daily Tribune, 9 December 1882, p. 12.

White, Richard Grant. "A Morning at Sarony's," Galaxy, March

1870.

"Will of Napoleon Sarony," New York Times, 18 November 1896,

p. 7.

"William Burrow, Head of Hospital," New York Times, 18 February

1941, p. 23.